Talk:Hindu Temples

Introduction[edit]

History has signified that man cannot live without God. Voltaire (A. D. 1694-1778) declared that, "If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him!". The base of any culture is the belief in God and cosmic Power or cosmic Laws in superhuman Spirit. Once this fact is recognized, it becomes irrelevant whether this belief has been brought about by man’s awe, wonder and fear of the powers of nature or by the teachings of god-men who had mystical experiences of the God.

Man is human and not divine. This is true till he is conscious of his frailties and impulses. Hence he turns towards the Divine in the times of necessity. Though the Divine transcends all the temporal limitations, man is human. He needs a temporary set-up that can help him visualize the Divine or establish contact with it. Fundamentally here the need of either a symbol, an image or a place of worship comes into picture.

Denominations of Temple[edit]

All the religions have their sacred places of worship. Various words which denote such places of worship, etymologically mean the same thing. The names used for the temple are:

- Devālaya - It means ‘house of God’.

- Temple - It means a building for religious exercises.

- Synagogue - It refers to a ‘house for communal worship’.

- Church - It is meant as the place for common exaltation.

- Masjid - It is a place of prostration before God.

History of Temples[edit]

Temples did not exist during the Vedic age. The practice of preparing images of the deities mentioned in the Vedic mantras might have come into vogue by the end of the Vedic period. Majorly accepted view point is that the yāgaśālās of the Vedic period gradually got metamorphosed into temples owing to the influence of the devotional sects.

Types of Temple Framework[edit]

The earliest temples were built with the perishable materials like timber and clay. Cave-temples, temples carved out of stone or built with bricks came later. Heavy stone structures with ornate architecture and sculpture belong to a more later period. Considering the vast size of the country, it is remarkable that the building of temples has progressed in a fixed set pattern. It is because there is a basic philosophy behind the temple, it's meaning and significance. In spite of the basic patterns being the same, varieties gradually lead to the evolution of different styles in temple architecture. Broadly speaking, these patterns can be bifurcated into three styles. These styles are:

- Northern style - It is technically called as nāgara. It can be distinguished by the other styles though it's curvilinear towers.

- Southern style - It is also known as drāvida. It has its towers in the form of truncated pyramids.

- Vesara style - This pattern combines both the northern and southern styles in it.

Survival of the Temples[edit]

In North and Central India[edit]

The earliest temples in north and central India which have withstood the vagaries of time belong to the Gupta period, 320-650 A. D. These temples are presently located at:

- Sanchi, Tigawa near Jabalpur in Madhya Pradesh

- Bhumara in Madhya Pradesh

- Nachna in Rajasthan

- Deogarh near Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh

In South India[edit]

Among the earliest surviving temples in South India are those found in Tamil Nadu and northern Karnataka. The cradle of Dravidan school of architecture was Tamil which evolved from the earliest Buddhist shrines. They were both rock-cut and structural. The later rock-cut temples roughly belonged to the period A. D. 500-800. They were mostly Brāhmanical or Jain. Three ruling dynasties of the south highly patronize them, namely:

- Pallavas of Kāñcī in the east

- Cālukyas of Bādāmi in the west

- Pāṇḍyas of Madurai in the far south

With the decline of the Cālukyas of Bādāmi in the 8th century A. D., the Rāṣṭrakuṭas of Malkhed came to power. They made great contributions to the development of south Indian temple architecture. The Kailāsanātha temple at Ellora belongs to this period.

In West India[edit]

In the west (northern Karnataka), the Aihole and Paṭṭadakal group of temples (5th to 7th centuries A. D.) evolve an acceptable traditional regional style. Among the early structural temples at Aihole, assigned to the period A. D. 450-650, are:

- Huchimalliguḍi temple

- Durgā temples

- Lāḍkhān temple

Temples of Paṭṭadakal near Aihole are also equally important. They are:

- Kāśīnātha temple

- Pāpanātha temple

- Saṅgameśvara temple

- Virupākṣa temple

- Svargabrahmā temple[1]

In some of these temples built by the later Cālukyas, we come across the vesara style which is a combination of the northern and the southern modes.

Adaptations in Styles[edit]

There are many ancient texts emphasizing the formal architectural styles prevalent in the various regions. One other comprehensive text called as the Vāstu Śāstra has its sources in the sutras, purāṇas, āgamas, Tāntric literature and Bṛhat Samhitā. But all of them basically agree on the nāgara, drāviḍa and vesara styles. Nāgara style deploy square plan. Drāviḍa style show octagon plan. The vesara style follows apse or circle in their plan.

Vesara style is the later evolution in temple artichecture. It adopted the square for the sanctum and circular or stellar plan was retained for the vimāna. These three styles do not strictly pertain to three different regions. They indicate only the temple groups. For instance, the vesara style, which mostly prevailed in western Deccan and south Karnataka, was a derivation from the apsidal chapels of the early Buddhist period. This faith was mostly adopted and vastly improved by the Brāhmanical faith. In its origin, the vesara is as much north Indian as it is west Deccanese.

Similarly among the 6th-7th century shrines of Aihole and Paṭṭadakal we find evidence of nāgara style in the prāsādas or vimānas. The drāviḍa or Tamilian style became very popular throughout the south India only from the Vijayanagar times onwards. The prāsāda or vimāna of the nāgara style rises vertically from its base in a curvilinear form and that of the drāviḍa rises like a stepped pyramid, tier upon a tier. The northern style prevailed more in Rajasthan, Upper India, Orissa, the Vindhyan uplands and Gujarat.

Growth in Temple Architecture[edit]

During the next thousand years from, A. D. 600 to 1600, there was a phenomenal growth in temple architecture both in quantity and quality. The first advancement in the series of southern or drāviḍian architecture was initiated by the Pallavas in A. D. 600-900.

Contribution by the Pallavas[edit]

The Pallavas laid the foundations of the drāvidian school which blossomed to its full extent during the periods of the Colas, the Pāṇḍyas, the Vijayanagar kings and the Nāyakas. The temples, now built of stone, became bigger, more complex and ornate with sculptures. The best representatives of the Pallava style architecture are:

- Rock-cut temples at Mahābalipuram of the ‘ratha’ type

- Structural shore temples at Mahābalipuram

- Kailāsanātha temple at Kāñcīpuram

- Vaikuṇṭha Perumāl temples in Kāñcīpuram (A. D. 700-800)

Contribution by Drāvidians[edit]

Drāvidian architecture reached its glory during the Cola period in A. D. 900-1200. It advanced by growing in size endowed with happy proportions. Among the most beautiful of the Cola temples is the Bṛhadīśvara temple at Tanjore with its 66 meter (218 ft.) high vimāna which is the tallest of its kind.

Contribution by Pandyāns[edit]

The later Pandyāns who succeeded the Colas improved by introducing:

- Elaborate ornamentation

- Big sculptural images

- Many-pillared halls

- New annexes to the shrine

- Towers (gopurams) on the gateways

Contribution by Nāyaks[edit]

The mighty temple complexes of Madurai and Śrīraṅgam in Tamil Nadu set a pattern for the Vijayanagar builders (A. D. 1350- 1565) who followed the drāvidian tradition. The Pampāpati and Vitthala temples in Hampi are standing examples of this period. The Nāyaks of Madurai who succeeded the Vijayanagar(A. D. 1600 to 1750) made the drāvidian temple complex even more elaborate by making the gopurams very tall and ornate. They added pillared corridors within the temple’s long compound.

Contribution By Hoysalas[edit]

Contemporaneous with the Colas (A. D. 1100-1300), the Hoysalas who ruled the Kannada country, improved on the Cālukyan style by building extremely ornate temples in many parts of Karnataka. These temples are noted for the sculptures in the walls, depressed ceilings, lathe turned pillars and fully sculptured vimānas (domes). Among the most famous of these temples are the ones at Belur, Halebid and Somanathapura in South Karnataka. These temples are classified under the vesara style.

Outstanding Examples of Architectural Advancement[edit]

Within India[edit]

In the north, the chief developments in Hindu temple architecture took place in Orissa (A. D. 750-1250), Central India (A. D. 950-1050), Rajasthan (10th and 11th century A. D.) and Gujarat (11th-13th century A. D.). The temples which portray distinct features of temple architecture are:

- Liṅgarāja temple in Bhubaneshwar

- Jagannātha temple in Puri

- Surya temple in Konarak

- Temples at Khajuraho[2]

- Surya temple at Modhera, Gujarat

- Delwara temples at Mt. Abu[3]

Brick temples of Bengal and terracotta tiles temples in Kerala have a peculiar root structure which suites the heavy rainfall of the region. These were developed by their own localized special styles.

Outside India[edit]

There are many Hindu Temples outside India, especially in the South East Asian countries. The earliest of these temples are found in Java. The Śiva temples at Dieng and idong Songo built by the kings of Śailendra dynasty (8th-9th century A. D.) is an excellent example of this. The group of temples of Lara Jonggrang at Pranbanan (9th or 10th century A. D.), is a magnificent illustration of Hindu temple architecture. Other temples worth mentioning are:

- The temple complex at Panataran, Java[4]

- The rock-cut temple facades at Tampaksiring of Bali (11th century A. D.)

- The ‘mother’ temple at Besakh of Bali (14th century A. D.)

- The Chen La temples at Sambor Prei Kuk in Cambodia (7th-8th century A. D.)

- The temple of Banteay Srei at Angkor (10th century A. D.)

- Angkor Vat complex (12th century A. D.)[5]

Similitude between Temple and God[edit]

The concept of a temple's plan and it's elevation is very significant. Horizontally, the garbhagṛha represents the head and gopuram denotes the feet of the deity. Other parts of the building complex are identified with other parts of the body. These representations are:

- Śukanāsī[6] or Ardhamaṇḍapa[7] - It resembles to the nose.

- Antarāla[8] - It is the neck.[9]

- Various mandapas are the body

- Prākāras[10] - They refer to the hands.

- Vertically the garbhagṛha represents the neck.

- Śikhara[11] - It represents the head.

- Kalaśa[12] - It represents the hair.

- Śikhā - It also signifies hair.

Symbology of the Temple[edit]

The temple is a link between a man and the God, between the earthly life and the divine life, between the actual and the ideal. Hence it is symbolic.

Insignia of the term Devālaya or Prāsāda[edit]

The word ‘devālaya’ is frequently used to denote a temple. It actually means ‘the house of God’. It is a place where God dwells on earth to bless mankind. It is His house. In fact, there is another word to denote a temple, ‘Prāsāda’. It means a palace with a very pleasing appearance. From this viewpoint, the dhvajastambha represents the flagpost on which the insignia of the deity is printed. The outer walls are called prākāra. They are the walls of the fort. The gopuram[13] is the main gateway.

Insignia of the term Vimāna[edit]

‘Vimāna’ is an another word which generally denotes a temple and the garbhagṛha (sanctum sanctorum) in particular. Etymologically it refers to a ‘well-proportioned structure’. On extending this meaning derived from the root-verb mā (= to measure), it signifies, God the Creator, as a combination of Śiva and Śakti. He ‘measures out’ this limited universe from Himself. It further means an aeroplane. It is the aeroplane of gods landed on earth to bless mankind.

Insignia of the term Tīrtha[edit]

Pilgrimage has an important place in the religion. A place of pilgrimage is called tīrtha and is invariably associated with a temple. Hence the temple is also called a tīrtha. The temple helps us to cross the ocean of sansāra (transmigratory existence).

Insignia Of Lokas[edit]

The temple also represents God in a cosmic form with the various worlds located on different parts of his body. The bhuloka (earth) forms his feet and satyaloka[14] forms his śikhā.[15] The other lokas[16] form the appropriate parts of his body. These resemblances are:

- The ground represents bhuloka.

- The adhiṣṭhānapīṭha is the base-slab below the image. It represents the world bhuvah.

- The stambhas are the pillars. It represents the world svah.

- The prastara are the entablature supported above the pillars. It represents the world mahah.

- The śikhara is the superstructure over the garbhagṛha. It represents the world janah.

- The āmalasāra is the lower part of the finial. It represents the tapah.

- The stupikā is the topknot or the finial. It represents the satyam.

Insignia of Meru Parvata[edit]

The temple also represents the Meru-parvata, the mythical golden mountain described in the purāṇas.[17] It is the central point of the universe around which the various worlds are spread. It also represents this world in all its actual and ideal aspects. The imposing gopurams at the entrance reflect the awesome grandeur of the external world. The friezes and the sculptures on the external walls of the temple depicts the animal world and the mundane life of the ordinary human beings including the ridiculous side and the aberrations. These are followed by the scenes from the epic and mythological literature along with the religious symbols and icons of gods and goddesses. It reminds the onlookers of the great cultural and spiritual heritage.

Insignia of the human body parts[edit]

If the temple symbolizes the body of God on the macrocosmic plane, it equally symbolizes the body of man on the microcosmic plane. The names of the various parts of the temple are the names used to denote the various parts of human body. These names are:

- Pādukā

- Pāda

- Caraṇa

- Aṅghri

- Janghā

- Uru

- Gala

- Grīva

- Kaṇṭha

- Śira

- Śīrṣa

- Karṇa

- Nāsika

- Śikhā

Pāda (foot) is the column, jaṅghā (shank) is part of the superstructure over the base. Gala or grīva (neck) is the part between mouldings which resembles the neck. Nāsikā (nose) is a nose-shaped architectural part and so on. The garbhagṛha represents the heart and the image symbolizes the antaryāmin (the indwelling Lord). This symbols try to impress the need to seek the Lord within our hearts rather than searching outside.

Insignia of Psychic Centers[edit]

The temple also represents the subtle body with the seven psychic centers or cakras. These symbols are:

- The garbhagṛha represents the anāhata cakra. It is the fourth psychic center in the region of the heart. It is at the topmost part of the kalaśa points to the sahasrāra. Sahasrāra means seventh and the last center situated at the top of the head.

- The first three centers are the mulādhāra, svādhiṣṭāna and maṇipura cakras situated respectively near the anus, sex-organ and navel. They are below the ground level.

- The fifth and the sixth are the Viśuddha and ājñā cakras. They are situated at the root of the throat and in between the eyebrows. They are on the śikhara area.

Insignia of Maṇḍala[edit]

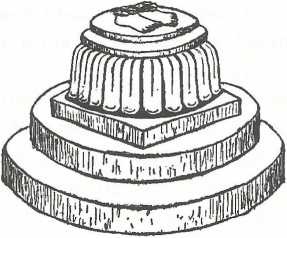

The ground-plan of a temple is known as maṇḍala. Hence whatever interpretations are given to a maṇḍala can also be extended to the temple. A maṇḍala is a geometrical diagram with occult potentialities. Symmetry is its chief characteristic. The created world perfectly handicrafted by the God can be best represented by a symmetrical and well proportioned maṇḍala.

A devotee moves from the outer the outer details to the center. It represents the one creative Principle, the Deity, from which everything has evolved. In a maṇḍala, the devotee has to start from outside, pass through circuitous routes and successive stages to come to the center. Similarly the devotee who enters the temple has to pass through several gates, courtyards and passages, leaving the grand externals. He should progress towards the garbhagṛha, heart of the temple complex, housing the one cosmic Principle.

Construction of a Temple[edit]

Building of the temples is considered to be an extremely pious act which brings great religious merits. Hence the kings and rich people spend their wealth on it eagerly. All the various steps involved in it's construction were observed either as the religious rites or with religious overtones.

Selection of Sthāpaka[edit]

The yajamāna[18] must first choose a proper guide, sthāpaka or ācārya for overall guidance and supervision. Designated ācārya must be a pious brāhmaṇa with a sinless life. He must be an expert in art, architecture and rituals. The ācārya then chooses the sthapati[19] and puts him in charge of the whole construction. The sthapati commands status and respect equal to that of the ācārya. He is assisted by:

- Sutragrāhin - surveyor

- Takṣaka - sculptor

- Vardhakin - builder, plasterer and painter

Selection of Site[edit]

From the day of saṅkalpa,[20] the yajamāna and the ācārya have to take certain religious vows and lead a very strict life in accordance with those vows. The first and foremost step in building a temple is the selection of a suitable site situated in or near a holy place. It should be endowed with natural beauty and peace. It is then cleared with its vegetation. The place is purified. Even the evil spirits are exorcised.

Vāstu-Vinyāsa[edit]

When the detailed designs and construction drawings are ready, vāstu-vinyāsa is developed. A vāstumaṇḍala is designed on the temple construction site at an appropriate auspicious time.

‘Vāstu-puruṣa’ is the cosmic man embodying the whole creation including the different deities of the Hindu pantheon in the different limbs and parts of his body. The maṇḍala is a geometrical drawing of 64 squares which represents him. Once the vāstumaṇḍala is drawn ceremonially, it becomes ‘alive’ with the Vāstupuruṣa fixed on it. Later, the image or the symbol of the deity is installed in the center of this maṇḍala at the appropriate time.

Aṅkurārpaṇa[edit]

Another important religious ceremony connected with the various stages of construction is aṅkurārpaṇa. It is the rite of germination of the seeds. Its main purpose is to facilitate the fruition of the work without obstructions and obstacles. It is performed before the construction starts. To be very precise, it commences before laying the last brick or stone[21] into the superstructure. The rituals of the installation of the main image, the ‘opening of the eyes’[22] of the image and other observances succeeds this rite. The rite consists of placing the seeds of different varieties of rice, sesamum, mustard etc. in 16 copper vessels in front of Soma, the lord of germination, and offering them to the concerned deity after germination.

Śilānyāsa[edit]

Śilānyāsa is also known as the ceremony of laying the foundation stone. It is the laying of the first square shaped stone or brick signifying the beginning of construction. It is laid in the north-western corner of the building plan. It is drawn on the ground after excavating the foundation to the required depth. After this, the construction of the foundation commences. The foundation is built and the ground is filled up to the plinth level except in the middle portion of the garbhagṛha which is filled up to three-fourths only.

Ṣaḍādhāra Pratiṣṭhā[edit]

In the center of the site, the ādhāraśilā[23] is placed. On this ādhāraśilā the following articles are deposited:

- A pot called nidhikumbha

- Tortoise and a lotus made of stones

- Tortoise and a lotus made of silver

- Tortoise and a lotus made of gold

A funnel-shaped tube called as yoganālā is inserted from there. It is made of copper and leads to the plinth. The whole thing is covered by another stone-slab called ‘brahmaśilā’. The image of the deity is established over this later on while consecration. This is called ‘ṣaḍādhāra pratiṣṭhā.’

Garbhānyāsa[edit]

Another extremely important rite which is performed during the temple construction is the garbhānyāsa ceremony. It is also known as the ‘insemination’ of the temple site. A casket or tray of copper, whose dimensions are proportional to the dimensions of the temple, is prepared. It is then ceremonially lowered into the ground on an auspicious night. It's 25 squares are filled with various articles and duly worshiped. It represents the Mother Earth. The ceremony is performed with a view to achieve the smooth consummation of the temple project.

Other Rituals[edit]

Materials used for construction like stones, bricks and wood should be new. There are particular guidelines for these materials and their sources. All the tools and implements used in the construction should be worshiped. After the foundation is built up to the basement level, the superstructure is built either with pillars, walls or a combination of both. Doors, openings, niches, windows and porches with suitable decorations are added at the appropriate stages. It ends with the śikhara, the crest or the finial. The most important part of temple construction is the preparation and installation of the image of the main deity and the subsidiary deities.

Essential Parts of A Typical Temple[edit]

Garbhagṛha[edit]

The most important part of a temple is the garbhagṛha or sanctum sanctorum. It is usually square with a low roof and no doors or windows except for the front opening. The image of the deity is stationed in the geometrical center. The whole place is completely dark except for the light that comes through the front opening. A small tower is over the roof of the whole shrine.

The tower on the roof of the temple is quite high in the North Indian style temples whereas it is of low or medium height in the South Indian style. In some temples, a pradakṣiṇapatha[24] is provided just around the garbhagṛha to enable the devotees to go around the deity.

Mukhamandapa[edit]

Both the types of temples other than vesara temples have this passage. In front of the garbhagṛha and contiguous to it is the mukhamandapa which is sometimes called as ‘śukanāsi or ‘ardha-maṇḍapa’, depending upon its proportion relative to that of the garbhagṛha. Apart from being used as a passage, it is also used to keep the articles of worship including naivedya[25] on special occasions.

Antarāla[edit]

Antarāla is a narrow passage connecting the garbhagṛha and the mukhamaṇḍapa to the maṇḍapa.[26] The antarāla is identical with mukhamaṇḍapa or śukanāsī.

Maṇḍapa[edit]

The maṇḍapa[27] is a big hall. It is used for congregational religious acts like:

- Singing

- Dancing

- Recitation of mythological texts

- Religious discourses

- Etc.

Dhvajastambha[edit]

One other common feature of any temple is the dhvajastambha.[28] It is situated in front of either the garbhagṛha, antarāla or the maṇḍapa. It represents the flagpost of the ‘King of kings’. The lāṅchana[29] made of copper or brass fixed like a flag to the top of the post varies according to the deity in the temple.

Balipīṭha[edit]

The figure on the lāñchana is invariably that of the vāhana[30] of the deity. For instance:

- Śiva temples has Nandi.

- Devī temple has Lion

- Viṣṇu temples has Garuḍa.

The balipīṭha[31] with a lotus or the foot prints of the deity is fixed near the dhvajastambha near the deity. Red-colored offerings like rice mixed with vermilion powder are kept on this at appropriate stages during the performance of rituals. This indicates feeding of the parivāra-devatās.[32] There are the evidences which prove that the yupastaribha[33] and balipīṭha of the Vedic age have become metamorphosed into the dhvajastambha and the balipīṭha.

Gopuram[edit]

The whole temple is surrounded by a high wall, prākāra, with one main and three subsidiary gates. These gates are the opening in the cardinal directions. A gopuram[34] adorns these gateways. Inside the prākāra, there might be minor temples or shrines for other deities connected with the main deity. For instance:

- In a Śiva temple, the minor shrines are dedicated to:

- Gaṇapati

- Pārvatī

- Subrahmaṇya

- Caṇḍeśvara

- In a Viṣṇu temple, the minor shrines are dedicated to:

- Lakṣmī

- Hanumān

- Garuḍa

- In a Durgā temple, the other shrines are:

- Śiva

- Gaṇapati

- Subrahmaṇya

Dīpastambha[edit]

Dīpastambha is the lamp-post in the temple. It is another constituent of a temple complex often found in South Indian style. It is situated either in the front of balipīṭha or outside the main gate. The top of this post has a bud-shaped chamber to receive the lamp.

Other Enclosures[edit]

Apart from the above mentioned sections, the temple precincts includes:

- Yāgaśālā - sacrificial shed

- Pākaśālā - cooking shed

- Place for the utsavamurti - processional image carried during the car-festivals

- Well or a puṣkariṇī - tank

- Flower garden

- Stores

- Other essential structures connected with the management of the temple and rituals

Iconography[edit]

Category of Images as per the Deity[edit]

Indian iconography[35] is a very ancient science and arts. There are clear references of the images and temples in the Ṛgveda and the Atharvaveda. Subsequent ancient works contain innumerable references of the same. Broadly speaking, the images in the temples fall into three groups:

- Śaiva - It is the sect of Śiva.

- Śākta - It is the sect of Śakti.

- Vaiṣṇava - It is the sect of Viṣṇu.

Classification of Images as per Ordinances[edit]

The images, can be of three types:

- Acala or dhruvabera - immovable. They are usually made of stone. These images are permanently fixed.

- Cala - movable. They are made of metals like bronze or pañcaloha.[36] These images are used for taking out in procession on festive occasions for bathing or for ritualistic worship.

- Calācala - This image is both movable and immovable. When the same image that is kept and worshiped in the grabhagṛha is also taken out on the ratha,[37] it is called calācala. The image in the temple of Lord Jagannātha at Purī in Orissa is the best example of this type of image.

Postures of the Images[edit]

The image of any deity can be in three possible postures:

- Sthānaka - standing

- Āsana - sitting

- Śayāna - laying down

Among all the deities, only the image of lord Viṣṇu is found in the śayāna posture.

Aspects of the Images[edit]

The aspects of the deities can be represented by the images. They can be determined by:

- Mudrā - position of the hands and fingers

- Āsana - posture of legs and feet

- Cinha - symbol

- Vasana - dress

- Ābharaṇa - ornaments

Mudrās and Āsanas of the Images[edit]

Among the mudrās and āsanas, the common ones are:

- Abhayamudrā - assuring protection

- Varadamudrā - granting boons

- Padmāsana - lotus posture

- Yogāsana - meditation posture

Contrivances of the Image[edit]

Generally the images of deities exhibit holding some or the other weapons or instruments. Śaiva and Śakta images have:

- Damaru - drum

- Triśula - trident

- Pāśa - noose

- Aṅkuśa - goad

- Bāṇa - arrow

- Khaḍga - sword

Vaiṣṇava images are too decked up in regards to dress and ornaments. They display the symbols such as:

- Cakra - discus

- Śaṅkha - conch

- Gadā - mace

- Padma - lotus

Rules for Sculpturing the Images[edit]

There are elaborate rules guiding the sculpturing of images. The height or length, width, girth and the proportions of the various limbs is determined according to the tālamāna system. A ‘tāla’ is the measurement of the palm of the hand.[38] It is equal to the length of the face.

The fundamental unit of the talamana system is the measurement of the palm and the face of the total length or height of the image wherein the navatāla system is nine times the length of the face. Navatāla system is recommended for the images of gods. In spite of all these rules and regulations, the sculptor had the freedom to show his skills. A beautiful face with the expression of the appropriate rasa[39] was not only commended but firmly recommended.

Religious Rites and Ceremonies[edit]

Consecration Ceremony[edit]

Consecration Ceremony is also called as the pratisthāvidhi. Once the construction of a new temple is successfully completed, it is formally consecrated with the appropriate rites and ceremonies. A separate shed is erected in the north-eastern corner of the main structure wherein all the important religious ceremonies are performed.

The consecration is a very elaborate religious ceremony. Some of the rituals of this ceremony are briefly described below:

- After the usual pujā and homa for the Vāstupuruṣa, nine balis (offerings) are given to the minor (and usually fierce) deities.

- It is done by placing the balis all-round the temple.

- The deities are then requested to leave the place permanently.

- The ācārya, yajamāna and their assistants enter the yāgaśālā and establish kalaśas[40] all around the place.

- After certain preliminary rites, homas are performed in the several homakuṇḍas[41] to propitiate the main deity of the temple and other associated deities.

- After the ceremonial opening of the eyes of the main deity,[42] ritual called as ‘adhivāsa’ ceremony is performed. There are three types of adhivāsa ceremony.[43]

- In the first ritual which is termed as ‘jalādhivāsa’ ceremony, the image is taken in the ratha to a nearby source of water like a river or a pond and immersed in it.

- After three days, the image is brought in the ratha to the yāgaśālā and kept in grains for another three days. This rite is called as ‘dhānyādhivāsa’.

- Then the image is taken out and put on a specially prepared bed for three more days. It is called as ‘śayyādhivāsa’.

- In the center of the garbhagṛha, a yantra,[44] some precious stones, minerals and some seeds are placed.

- Then the ritual called as aṣṭabandha is performed. Eight materials like conch, whitestone, lac, perfume etc. are powdered nicely and mixed with butter or oil to form a paste. This paste is applied on the yantra and other mentioned materials. Image is fixed over this.

- Then the image is connected by a gold wire or a long thread to the main homakuṇḍa in the yāgaśālā. This is called ‘nādisandhāna’. The nāḍis or internal passages are opened up as if to receive life.

- The deity is then invoked into the image by prāṇapratiṣṭhā.[45] A simple worship is performed then.

- The main kalaśa from the yāgaśālā is brought and the image is bathed with that water. This is called ‘kumbhābhiṣeka.’

- The ritual of abhiṣeka is followed by elaborate worship, offerings and waving of lights.

- The ācārya, yajamāna, sthapati and their assistants then take a ceremonial bath.[46]

- It indicates that they have successfully completed a great and meritorious act. Then the devotees and poor people of the place are sumptuously fed.

Daily Worship[edit]

Daily worship is called nityapuja. Once a temple is built and ceremonially consecrated, daily worship must be done regularly. One can daily worship from a minimum of one time to the maximum of six times.[47] During each worship, all the dress and ornaments of the deity are removed. Then the image should be bathed successively with oil, ghee, milk, water and scented water. Then it is dressed again, smeared with sandal paste and decorated with ornaments.

Food articles are then offered. All these are done after closing the doors of the garbhagṛha. On the opening of doors, waving of lights and several upacāras[48] are done along with chanting of hymns and music. Ceremonial worship is done to the consort of the main deity and minor deities associated with it.

Occasional Worship[edit]

Worship done on special occasions like Śivarātri, Vaikuṇṭha Ekādaśī or Dasara is called ‘naimittika-pujā.’ This worship differs from place to place or from temple to temple. It is done in addition to the daily worship. Distinct feature of this worship is:

The utsavamurti is meant to be taken out in procession. It is well-decorated and exhibited to the devotees.

Rathotsava and Brahmotsava[edit]

On the special occasions mentioned above, religious celebrations may be spread over a number of days. The biggest festival among these is called ‘Brahmotsava’.[51] This is also called rathotsava since the utsavamurti is taken out in a procession in the temple car. Some of the important aspects of the festival are:

- Beating the drum[52]

- Hoisting the flag of the deity.[53]

- Inviting the deity to the yāgaśālā.[54]

- Establishing the kalaśas

- Performing homa

The temple car is taken out for two days before concluding the festival. In some temples where there are facilities of a river or a big tank, teppotsava[55] is the center of attraction. A procession is carried out with music, lights, crackers and entertainment. Hundreds of devotees, without any distinction of caste, creed or color, draw the car. Devotees who are unable to go to the temple due to any reason, can have the darśan at their doorsteps. They can even offer their private worship.

Temple Arts and Crafts[edit]

Kings are considered as the lords and masters of the country they rule. They were well-known for their fortification towards arts, crafts and artisans. Hence the temple which is the house of God, also should be magnificently elaborate. Consequently the temples, especially the bigger ones, form the biggest employers providing the greatest security and encouragement to the artisans and artists. Development of the crafts and their flourishing trade over the centuries, is largely due to the temples. Apart from sculpturing stone images or casting metallic ones, the other arts and crafts associated with the temples can be listed as follows:

- Music

- Dance

- Preparation of musical instruments

- Embroidery work on cloth

- Tailoring

- Preparation of perfumes and scents

- Making flower-garlands

- Cooking of special dishes

- Astrology

- Building Ratha

- Etching or embossing on metal plates used in various ways

- Making of lamp-posts and stands as also pujā vessels in brass

- Bronze and copper

- Painting

- Gold and silver smithy

- Ivory- craft

- Etc.

Temple and the Devotee[edit]

When we want to meet our superiors, we observe certain etiquette, norms and decorum. Therefore it is but natural that the devotee, who wants to visit the Lord of the universe in a temple, is expected to observe certain code of conduct. Taking bath, wearing freshly washed clothes is must. If and when possible, it should be done in the Puṣkariṇī attached to the temple.

Worship Regime[edit]

- While entering the precincts of the temple, he should observe silence and try to engage the mind in the thoughts of God.

- After doing the darśan and worship of the deity, he should circum ambulate the main shrine three, five or seven times.

- Then he should bow down to the deity from a place outside the dhvajastambha.

- He has to takes care that while bowing down his feet do not point in the direction of any of the minor deities.

- Visiting the shrines of the minor deities is his next duty. Before leaving the precincts of the temple, he should sit quietly in some corner and meditate.

- Since distribution of alms to deserving beggars in the vicinity of the temple is considered meritorious, the devotees are advised to do so.

Restrictions Inside the Temple[edit]

Apart from these general rules to be observed by the devotee, he should also be aware of daivāpacāras, modes of behavior, which will offend the deity in the temple. This is very important because when a temple is built and the image is consecrated ceremonially, the power of the deity manifests through that image. This is technically called arcāvatāra. The following are some of the modes of behavior, to be observed in the temple, which will offend the deity and bring misery and sufferings upon the transgressor:

- One should avoid the personal rules.

- Environmental and ceremonial cleanliness should be maintained.

- One should not miss the important festivals of the temple.

- A devotee should alwas make the obeisance or circumambulation.

- One should restrict the careless handling of the things offered to the deity.

- A devotee must offer the best things if he can afford to do so.

- He should not dispose the offered articles to the people who have no faith or devotion.

- One should never engage in secular and nonreligious activities in the presence of the deity.

- Boisterous behavior in the temple is strictly restricted.

- A person is expected to follow the caste restrictions.

- No one should misuse the things belonging to the temple.

- Etc.

Temple and the Priest[edit]

Role of a priest in a temple is very eminent. Since it is the chief responsibility of the head-priest and his assistants to maintain the spiritual atmosphere of the temple, a strict code of conduct is admonished upon them. Some of them are briefed below:

- They are expected to lead a very pure and pious life.

- They should know all the rituals and ceremonies connected with the temple worship and festivities.

- They should observe all the rules concerning personal and ceremonial purity.

- They should perform the worship with śraddhā (faith) and devotion.

- They should not misuse the temple property ny any means. In fact, they are expected to protect it.

- They should have genuine concern for the devotees.

- They should treat the followers with sympathy and understanding.

- Broad-mindedness and a liberal outlook is an additional qualification required for modern day priests.

Temple and the Society[edit]

Authority of Temple[edit]

Throughout the history, temple has exercised an enormous influence on the social life. Temples have been one of the eminent factors in motivating the society to follow and imbibe dharma in their lives. It's shrine and icons have given peace to the frustrated minds. The religious and musical discourses[56] of the temple have helped the propagation of the religion. Music, dance and other fine arts have received a great encouragement and provided pure and upgrading entertainment to the devotees.

Aid and Abet of the Temple[edit]

The construction and maintenance of the building have provided employment to the architects, artisans, sculptors and laborers. Being a center of learning, the temple helped in the acquisition and propagation of knowledge. Both scholars and students found shelter here. With its enormous wealth, it also acted as a bank to the needy by donating easy credits. The granaries of the temple feed the hungry people and persons unable to earn the livelihood due to disease and deformity. Many hospitals and dispensaries are being run by the temple. The temple often played the role of a law court for settling disputes. It also gave shelter to the people during wars. Overall, a temple was the social life of the country for centuries.

Devadāsīs, A Disposition[edit]

The system of the temple-dancers, commonly known as devadāsīs, was prevalent in ancient times. The concept behind this arrangement was that if the god in the temple is considered to be a living being, it is natural that the devotees should offer him all the enjoyments to which an emperor or a king is entitled to. The system of offering unmarried girls to the temple for the service of the deity originated due to this notion. This is not peculiar only to India. There are evidences to prove that in ancient Babylonia, Cyprus, Greece, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Syria,Arabia, and in the South East Asian countries such a system existed.

This system was opposed by the brāhmaṇas. However, due to the pressure of the kings and noblemen it was deferred. The girls chosen to become devadāsīs would marry the deity of the temple in a ceremonial way. Their main duties consisted of cleaning the temple, fanning the image, carrying lights, singing and dancing before the deity, devotees and others.

The system might have started during the 3rd century A. D. It soon degenerated into prostitution due to the notorious human weaknesses. The practice of the kings and noblemen, to entertain their important guests with music and dance by the slave girls and maids of their harem, might have been extended to the devadāsīs also. This extended to the limit of prostitution in course of time. Eventually, with the growth of society, this system was impeded.

Epilogue[edit]

Thus one can coclude that the temple which represents God and His abode, creation and the Creator, man and his true Self, has played a very insignificant part in the life of our society. Today, when its effect has waned considerably, the study of the maladies affecting it and searching for the appropriate remedies is worth.

The basic malady of this arrangement was the lack of proper organisation. It is due to some of the non proper arrangements. The Hindu society as a whole suffer from an utter lack of discipline due to the absence of a central church controlling all the sections of the society and claiming the loyalty from all. This is a big urgent problem which needs some attention. It can be solved when the highly respected and influential religious leaders of the society make earnest attempts to tackle this problem on the priority basis. Hindus have huge catholicity to accept all the great religious systems of the world as equally valid and true. They can certainly extend that catholicity towards their own innumerable sects and groups thereby achieving greater amalgamation.

While restoring the temples to their former glory and pride of place, the first problem that confronts us is that of the many historical temples which are in dilapidated condition and regular worship has been totally abandoned. Then there are temples where worship is still in vogue but which needs renovation badly. The need to build new temples in the new townships and colonies coming up all-over the country, especially in industrial project areas, cannot also be overemphasized. Hence the constitution of an All India Temple Trust to which not only devotees but also the richer temples in the country will contribute should seriously be considered. This should be an autonomous body and can release the funds to the concerned temple projects as and when necessary.

The second important problem is the one concerning the priests and other staff managing the temple. Efforts should be made to set up enough number of institutions to train the priests properly with the āgamaśāstras. Only such trained personnel should be employed in the temples. Though simple living and high thinking should be a basic concept to be integrated with their training, they should be paid decent salaries so that they are not forced to develop the ‘panda-psychology’ which is now rampant. This psychology should not be entertained.

Apart from the spiritual atmosphere, even the physical atmosphere in the precincts of the temple, is equally important. Physical atmosphere is always conducive to the spiritual arena. The churches and mosques, even in the remote or in the socially and culturally backward areas, are kept clean. The votaries of these two religions (Christianity and Islam) maintain good discipline during their community prayers and worship. This is lacking among the Hindus.

Our third denominations should be on keeping the temples and the surrounding areas clean, maintaining discipline like following the queue system, observing silence at the time of worship and reasonable quietness at other times. These are the virtues that needs to be inculcated among our people. Only the meagre temple staff cannot perform such tasks. The devotees living in the vicinity of the temple should volunteer corps of active men and women including students, who can take turns to keep the temple area clean and educate the people visiting the temple. Religious organisations can conduct short-term courses to train these volunteers. These volunteers will prove to be an asset during the festivals and rathotsavas. While these celebrations they can perform other duties like taking care of the footwear, vehicles and personal belongings of the visiting devotees, regulating the queues, helping the aged and the infirm, distributing drinking water, giving emergency medical aid and so on.

Propagation of our religion among our people or to put it succinctly, ‘Hinduising the Hindus’, is another grave problem. Temples can play an active role in deciphering it. Production of Hindu religious literature written in non-technical and popular language at a cheap price is one of the effective methods of such propaganda. The volunteers can help in the sale of such literature. Organizing regular classes on Hinduism, both for children and adults, is another activity that can be undertaken by the temples. Religious discourses, community bhajans, harikathas and staging of dramas which are in vogue even today can be organised in more systematic ways.

One of the banes of the Hindu society is the tendency to convert cash into ornaments instead of spending the same on socially useful channels like increasing the facilities for the devotees and pilgrims visiting the temple, better emoluments to the temple staff, beautifying the area to create a better atmosphere and so on, apart from what has already been mentioned earlier.

The ignorance of the Hindus about their own religion is not only colossal but also ignominious. The bigger temples with larger incomes, can organize permanent exhibitions depicting the salient features of our religion and culture. The millions of devotees who visit these temples every year can be educated with the fundamentals of our great religion. The bigger temples can also think of running educational, cultural and medical institutions to serve the public.

Marriage is the most important sacrament in the life of a Hindu. The influence of Western culture is having a deleterious effect upon this. If marriages are compulsorily performed in the temple premises, or at least solemnized by a suitable ritual in a temple, it may have greater stabilizing effect. In addition, the Hindus should feel obliged to attend all the important festivals of a temple and perform at least one important worship of their family in it.

The temple has occupied the central place in the society for centuries. It has been the greatest single factor in keeping it intact. There is no reason why it should not be revitalized so that it can play even greater roles in the future. It is the sacred duty of all the leaders of the Hindu society to make every effort in this direction.

References[edit]

- ↑ This temple is at Ālampur in Andhra Pradesh.

- ↑ These temples were built by the Chandellas.

- ↑ These temples were built by the Solaṅkis.

- ↑ This temple was built by the kings of Majapahit dynasty (14th century A. D.).

- ↑ It was built by Surya Varman II.

- ↑ It is also spelled as sukhanāsi or sukanāsī.

- ↑ It is the small enclosure in front of the garbhagṛha.

- ↑ It is the passage next to the previous one, leading to the main maṇḍapa called nṛtta-maṇḍapa.

- ↑ In many temples the antarāla is merged with the śukanāsī and not built separately.

- ↑ They are the surrounding walls.

- ↑ Śikhara is the superstructure over the garbhagṛha

- ↑ It is finial.

- ↑ Gopuram is the high tower at the entrance.

- ↑ Satyaloka is also called Brahmaloka.

- ↑ Śikhā means tuft of hair.

- ↑ The other lokas comprise of bhuvarloka, svarloka, maharloka, janaloka and tapoloka.

- ↑ Purāṇas are the Hindu mythological literature.

- ↑ Yajamāna is generally known as the sacrificer; but here he is referred as the financier and builder.

- ↑ Sthapati is the chief architect.

- ↑ Saṅkalpa means religious resolve.

- ↑ The last stone is called murdheṣṭakā.

- ↑ The ritual of opening the eyes is called as akṣimocana.

- ↑ Ādhāraśilā is the base stone.

- ↑ Pradakṣiṇapatha is a circum-ambulatory passage.

- ↑ Naivedya is the food offerings.

- ↑ Maṇḍapa is the pavilion or hall.

- ↑ Maṇḍapa is also called ‘nṛtta-maṇḍapa’ or ‘navaraṅga’.

- ↑ Dhvajastambha is the flagpost in the temple.

- ↑ Lāṅchana is the insignia.

- ↑ Vāhana is the carrier vehicle.

- ↑ Balipīṭha is the pedestal of sacrificial offerings.

- ↑ Parivāra-devatās are the attendant and associate deities.

- ↑ Yupastaribha is the sacrificial post.

- ↑ Gopuram is the high tower, sometimes called as the Cow-gate.

- ↑ Iconography is the science of preparing the images.

- ↑ Pañcaloha is the alloy made of five metals.

- ↑ Ratha is the temple car.

- ↑ It starts from the tip of the middle finger to the wrist.

- ↑ Rasa means emotion or sentiment.

- ↑ Kalaśas are the ceremonial pots filled with water, the number being up to a maximum of 32.

- ↑ Homakuṇḍas can be 1 or 5 or 9.

- ↑ This ritual is termed as netronmīlana.

- ↑ Adhivāsa means abode.

- ↑ Yantra is a gold plate with occult designs

- ↑ Prāṇapratiṣṭhā is the ceremony for infusing life-force.

- ↑ This bath is called ‘avabhṛtha-snāna’.

- ↑ Before sunrise, after sunrise, between 8 and 9 a.m., noon, evening and night.

- ↑ Upacāras are the items used in special service.

- ↑ Japa means the repetition of the divine name

- ↑ Abhiṣeka means bathing the image.

- ↑ Brahma means big.

- ↑ It is called bherītāḍana.

- ↑ It is called as dhvajārohaṇa.

- ↑ It is called āvāhana.

- ↑ Teppotsava is the boat-festival.

- ↑ These discourses are pravacanas and harikathās.

- The Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Swami Harshananda, Ram Krishna Math, Bangalore