Talk:Commentary on Īśāvāsya Upaniṣad: Karmyog

By Vishal Agarwal

Context

With the spiritual frame of mind taught in the preceding verse, one should perform one’s duties ceaselessly. This is the central teaching of the present mantra.

Mantra 2 Devanāgarī

कुर्वन्नेवेह कर्माणि जिजीविषेच्छतं समाः । एवं त्वयि नान्यथेतोऽस्ति न कर्म लिप्यते नरे ॥ २ ॥

(Same in both Śākhās)

IAST Transliteration

kurvann eveha karmāṇi jijīviṣec chataṃ samāḥ | evaṃ tvayi nānyathā ito’sti na karma lipyate nare || 2 ||

Translation

By performing action alone here, one should desire to live for a hundred years. For you, this is the only way, there is no other. Actions do not taint such a person. Īśāvāsya Upaniṣad 2

Purport

One must not seek the Truth by abandoning the world or by renouncing one’s duties. Such withdrawal is not the path to mokṣa. Rather, one should wish to live a full life of a hundred years, actively engaged in the selfless performance of one’s duties for as long as one lives. This alone is the path prescribed for human liberation, and not its opposite.

All actions inevitably bear fruit—good or bad—and these fruits bind the ātmā, causing rebirth. However, the fruits of action do not taint the wise person who performs duties selflessly as an offering to the Lord, just as a lotus leaf remains untouched by water though it rests upon it. On the other hand, one who, through ignorance, avoids his duties deludes himself by thinking, “I am not performing any action,” for no human being can remain without action even for a single moment.

Notes

This verse teaches that one should always perform prescribed duties while mentally relinquishing the fruits thereof in favor of God. Both performing good actions with desire for their results and neglecting one’s duties are hindrances on the path to mokṣa. Freedom from karma does not arise from abandoning action, but from performing action continuously without attachment.

The spiritual path is not one of inertia or laziness, but of constant striving. Hence the Kaṭha Upaniṣad declares:

Devanāgarī

उत्तिष्ठत जाग्रत प्राप्य वरान्निबोधत ।

IAST

uttiṣṭhata jāgrata prāpya varān nibodhata |

“Arise, awake, and stop not until the goal is reached.” Kaṭha Upaniṣad 1.3.14

Everyday examples include a banker who handles vast sums of money daily without attachment, knowing that it is not his own, or a diligent nurse who serves many patients without excessive elation or grief over outcomes. Both remain steadily focused on their duties without attachment.

This verse of the Īśāvāsya Upaniṣad anticipates the doctrine of niṣkāma karmayoga, which is taught in great detail in the Bhagavad Gītā.

Illustrations The Royal Ṛṣis

The Upaniṣads mention jñānī kings such as Aśvapati Kaikeya and Janaka, whose social and political roles required them to perform their royal duties on a daily basis. The Mahābhārata (12.320.4) refers to Dharmdhvaja Janaka, the king of Mithilā, who attained the fruit of sannyāsa while remaining both a householder and a ruler. The Mahābhārata (12.320.24) mentions Pañcaśikhā as a bhikṣu belonging to the Parāśara gotra. Verse 27 records Dharmdhvaja Janaka stating that Pañcaśikhā imparted to him the complete wisdom of Sāṃkhya, yet did not permit him to renounce the world and become an ascetic.

In the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, we similarly read of King Priyavrata, who was a realized jñānī while actively ruling his kingdom.

Chapter 18 of the Śānti Parva (Book 12) of the Mahābhārata records a dialogue between King Janaka, who desired to adopt the life of an ascetic, and his queen, who reasoned with him against this inclination. She convinced him that, as a king, he could serve the devas, gurus, and society at large far more effectively than by renouncing the world. She emphasized the greatness of the householder, who generates wealth and sustains all other sections of society.

Furthermore, she explained that asceticism is primarily a mental state. One who is formally an ascetic yet remains attached to selfish motives and worldly objects is a hypocrite. Conversely, one who is not formally an ascetic but is self-controlled and serves ascetics and gurus with reverence and gifts is also truly an ascetic. Recognizing the soundness of his wife’s reasoning, King Janaka abandoned his desire to become an ascetic.

Story: The Brāhmaṇa Sannyāsī Jājali Accepts the Superiority of the Vaiśya Tulādhāra[1]

A brāhmaṇa ascetic named Jājali spent several years studying the scriptures and practicing meditation and other austerities. As a result, he acquired great powers of self-control. One day, while he stood absorbed in meditation, a pair of birds began hovering over his head. They soon started constructing a nest upon it. Moved by compassion, Jājali refrained from shaking his head, fearing that he might frighten the birds away.

Standing motionless, he allowed the birds to complete the nest and lay a few eggs in it. Not wishing to harm the eggs, Jājali resolved to remain still until they hatched. When the eggs hatched and the young birds emerged, he continued to stand unmoving for many days, exercising extraordinary self-control. Day after day, the parent birds traveled long distances to bring food and feed their offspring. Within a few weeks, the fledglings grew strong, matured, and finally flew away from the nest on Jājali’s head to begin independent lives. Throughout this entire period, Jājali remained steadfast in meditation, not moving his neck or head lest the birds be harmed or disturbed in any way.

However, this remarkable achievement, born of years of austerity, unfortunately gave rise to a subtle sense of pride. He thought to himself, “Who else could have accomplished such an extraordinary feat?” No sooner had this thought arisen than a voice resounded from the sky, saying, “Do not become conceited, Jājali. Your glory is not equal to that of the shopkeeper Tulādhāra of Vārāṇasī. And yet, even he does not utter words of self-praise such as you have just done.”

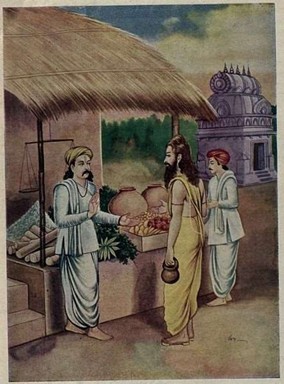

Jājali felt somewhat affronted, but nevertheless resolved to travel to Vārāṇasī to learn what Tulādhāra had to teach. Upon arriving at the shop, he found Tulādhāra engaged in weighing spices, vegetables, grains, and other goods for his customers. Seeing Jājali, Tulādhāra remarked, “I knew that you would come to see me to learn dharm.”

This astonished Jājali even more. He asked, “How did you know that I was coming to see you? And how can you, a mere shopkeeper, instruct me in dharm?”

Tulādhāra replied, “Most people in this world follow dharm for selfish reasons. Some desire to attain heaven by performing virtuous karma. Others, like you, derive self-satisfaction and happiness through acts of compassion. You have spent your life studying the śāstras and practicing meditation. But these alone do not automatically lead to a true understanding of dharm.”

Source: Mahābhārata, Śānti Parva. Narrated by Bhīṣma to King Yudhiṣṭhira.

Tulādhāra continued:

“Observe the weighing scale that I use to measure goods before selling them. I always weigh honestly, and the beam of my scale remains perfectly balanced. I neither give less nor more, regardless of whether a customer praises me or criticizes me. I practice honesty not out of desire for praise or fear of blame, but because I have faith in honesty itself. I seek the welfare of all creatures and work diligently to serve others—not for the pleasure of self-satisfaction, but because I have faith in Brahman. I know that this same Brahman dwells in all beings. Therefore, I must act for the good of all and give each their rightful due. This, I believe, is the true essence of dharm: equanimity towards praise and blame, selfless action for the welfare of all, and unwavering faith in Brahman.”

As Tulādhāra spoke these words, the birds appeared from the sky and declared that although Jājali had been like a father to them, Tulādhāra had indeed spoken the truth concerning the essence of dharm. Jājali now realized that while one must avoid evil karma and perform good karma, the highest path lies in performing good actions not for self-gratification or fear of criticism, but for the welfare of all beings and with faith in goodness and in Brahman.

Embracing this understanding of dharm, Jājali practiced it diligently and eventually attained mokṣa.

Story: The Sannyāsī Learns from the Devoted Housewife and Dharmavyādha, the Righteous Meat-seller

A young brāhmaṇa boy named Kauśika, living with his elderly parents, suddenly decided to become an ascetic in order to pursue the spiritual path. His parents begged him not to abandon them, for they were old, he was their only child, and they were entirely dependent upon him. However, the boy paid no heed to their lamentations and left them without compassion.

Kauśika went to live in a forest on the outskirts of a village. He spent most of his days in meditation and other spiritual disciplines. At midday, he would go to the village to beg for food.

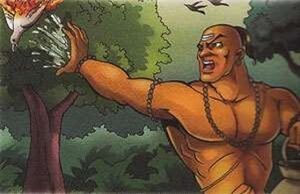

One day, while walking toward the village, bird droppings fell upon his body. Looking up, he saw a crane perched on a tree branch above him. Enraged by this, he cast an angry glance at the bird, whereupon it instantly burst into flames and was reduced to ashes.

Kauśika was astonished. It became evident that he had acquired extraordinary powers through his prolonged meditation. He felt proud and gratified, thinking that the bird deserved its fate for having defiled him.

Thereafter, Kauśika approached a house in the village to beg for alms. From inside, the lady of the house requested him to wait for a few minutes until she finished serving her husband. The boy waited, but the lady did not emerge immediately. He became irritated and thought to himself, “How dare she make a great man like me wait so long? Does she not know that I can curse her and burn her to ashes with my anger?”

Just as this thought arose, the lady called out from within the house, “O brāhmaṇa boy, I am not like that poor crane that can be burnt to ashes by your anger. Please wait, for I must complete serving my husband before coming to give you food.”

Kauśika was stunned. How could she have known his thoughts? He had spoken to no one, and she had not even seen him. When she finally came out with the food, she apologized for the delay, explaining that it was her duty to serve her husband before attending to anyone else.

Unable to restrain his curiosity, Kauśika asked her how she could read his mind when he himself had taken many years of austerity to gain spiritual powers. The lady replied, “I am a simple housewife and completely uneducated. I know only that it is my duty to serve my husband and family with devotion. This itself is my worship. Beyond this, I know no spiritual doctrine. However, if you wish to learn deeper spiritual truths, go to Mithilāpurī. There lives a butcher named Dharmavyādha. He keeps a meat shop in one of the streets there and may be able to instruct you.”

Excited and curious, Kauśika immediately set out for Mithilāpurī. After asking several people, he eventually reached Dharmavyādha’s meat shop. He was appalled by the sight—it was dirty, foul-smelling, and filled with blood and chopped meat. Nevertheless, he introduced himself to Dharmavyādha, who said, “Please give me some time to serve my customers. When I am finished, we shall go home, and then you may ask me about spiritual matters.”

Kauśika sat there waiting, deeply repulsed by the butcher’s occupation. He wondered why the housewife had sent him so far to meet such a person and how a butcher could possibly know anything about spirituality.

In the evening, after the day’s work was done, Kauśika followed Dharmavyādha to his home, where the butcher lived with his aged parents. Dharmavyādha respectfully offered the boy a seat. From there, Kauśika observed the butcher lovingly serving fruits, milk, and water to his elderly parents with great reverence. Only after attending to them did Dharmavyādha turn to Kauśika, and the two began a discussion on philosophy and spiritual wisdom.

Kauśika was astonished by the butcher’s depth of knowledge, intelligence, and spiritual insight. He realized that he had been foolish to abandon his aged parents in the pursuit of spirituality. Though proud of his individual accomplishments, he now saw that they were insignificant compared to the spiritual stature of the humble housewife and Dharmavyādha. Neither had neglected their duties; instead, they faithfully served their husband and parents with love, day after day, worshipping God inwardly. They worked without expectation of reward, simply because they regarded the fulfillment of dharma as their natural obligation.

Through such selfless action, they had attained spiritual enlightenment by the path of karma-yoga, as taught in the Bhagavad Gītā.

Kauśika then returned to his aged parents and served them devotedly. In due course, he married and raised a family. When he became old, after his parents had passed away and his children were settled, he formally accepted sannyāsa and eventually attained mokṣa.

Story: The Karmayoga of the Poor Farmer Surpasses the Bhakti of Nārada

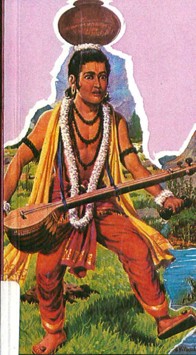

The divine sage Nārada Muni incessantly traveled from one world to another, chanting praises of Bhagavān Viṣṇu. Over time, however, a subtle pride entered his heart, and he began to regard himself as the greatest devotee of Viṣṇu. Wishing to verify whether this self-assessment was correct, he approached Kṛṣṇa and asked, “Bhagavān, whom do You consider to be Your greatest devotee on this earth?”

Kṛṣṇa replied, “This is indeed a difficult question. But come with Me; I shall take you to the home of a farmer living in Hemakūṭa. He, I believe, is My greatest devotee.”

Kṛṣṇa and Nārada assumed disguises and arrived at the farmer’s humble dwelling just as the sun was setting. The farmer’s wife had just served food to her husband and their two children. Seeing strangers at his doorstep, the weary and exhausted farmer welcomed them inside and asked whether they needed anything. The visitors requested some food.

The only food available was what the farmer’s wife had prepared for the family. The farmer therefore offered his portion to the guests, and seeing that there were two visitors, his wife also gave them her share. The guests then expressed their desire to rest for the night. As the hut was very small, the farmer, his wife, and their children slept outside, generously offering the hut to the visitors.

The following morning, the farmer and his wife prepared more food and served it to the guests as breakfast. Kṛṣṇa (still in disguise) then expressed a wish to see the farmer’s fields. The farmer invited them to accompany him. There, he began plowing the land laboriously with his bullock, explaining to Kṛṣṇa and Nārada the arduous nature of agricultural work.

After several hours, when it was time to rest, Kṛṣṇa asked the farmer, “You remain occupied all day working in the fields. You return home, tend to your buffalo, eat the meager food your wife prepares from your limited income, spend a little time with your children, and then fall asleep exhausted. Do you ever find time to remember Bhagavān?”

The farmer replied, “I am a poor man who must labor constantly to support my family and animals. Still, I remember Bhagavān three times each day—when I walk to the fields in the morning, when I return home at sunset, and just before I sleep at night.”

Nārada smiled inwardly upon hearing this and thought, “He remembers Bhagavān only three times a day, whereas I remember Him thousands of times. Surely Viṣṇu will now realize that I am the greater devotee.”

Kṛṣṇa, perceiving Nārada’s thoughts, decided to teach him a lesson. As the visitors prepared to depart, the poor farmer offered them a pitcher of oil, saying, “This oil is extracted from the mustard seeds that I grow. Please accept it as a humble gift.”

After they had walked some distance, Kṛṣṇa said to Nārada, “Place this pitcher of oil upon your head and walk carefully, ensuring that not a single drop is spilled.” Nārada complied. The task proved extremely difficult, and he remained tense throughout. After some time, Kṛṣṇa asked him, “How many times did you remember Me while carrying that pitcher?”

Nārada replied, “I was so anxious about spilling the oil that I did not remember You even once.”

Kṛṣṇa smiled and said, “Observe that humble farmer, Nārada. His life is filled with hardship. He works tirelessly for a meager income and bears the heavy burden of responsibility for his family—far heavier than this pitcher of oil. Yet he performs his duties without pride and remembers Me with devotion three times each day. Do you think your life is more difficult than his? Do you think he is inferior simply because he does not chant My name incessantly, while you, a wandering ascetic, are free from worldly responsibilities?”

Nārada was humbled. He realized that the farmer performed his svadharma with devotion, composure, and a sense of duty. Though he remembered Bhagavān only three times a day, every action of his life was, in truth, an act of worship. His three daily remembrances merely served to consciously dedicate the entire day’s karma to Viṣṇu.

References[edit]

- ↑ Mahābhārata, Shānti Parva. Narrated by Bheeshma to King Yudhishthira.