Talk:Commentary on Īśāvāsya Upaniṣad: Mysterious Nature of the Divine

By Vishal Agarwal

Context The following two mantras of the Īśāvāsya Upaniṣad describe the profoundly mysterious and paradoxical nature of Brahman, who transcends the reach of the senses, the mind, and even the cognitive powers of the Devas. Brahman is presented as immanent yet unreachable, motionless yet surpassing all movement, forming a central Upaniṣadic meditation on transcendence and immanence.

Mantra 4

अनेजदेकं मनसो जवीयो नैनैव देवाः आप्नुवन् पूर्वमर्षत् । तद्धावतोऽन्यानत्येति तिष्ठत्तस्मिन्नपो मातरिश्वा दधाति ॥ ४ ॥

Translation The One that is unmoving is yet swifter than the mind. The Devas could not reach It, for It always went before them. Though standing still, It surpasses all that run. By It, Mātarīśvan, the vital air, supports the waters.

Īśāvāsya Upaniṣad 4

Purport Brahman, the Supreme Reality, is unique and without comparison, revealing itself through profound paradox. Though all pervading and ever present, Brahman remains inaccessible to the grasp of the mind. The mind, despite its remarkable subtlety and speed, cannot comprehend Brahman in its fullness. Whenever the intellect believes it has arrived at understanding, it discovers that Brahman exceeds all such conceptual boundaries.

The inability to comprehend Brahman is not due to spatial distance, for Brahman does not move from one location to another and is always immediately present. Rather, Brahman appears remote because it transcends all instruments of perception and cognition. Even the Devas, endowed with superior faculties, fail to apprehend its true nature, thereby underscoring the inherent limitation of sensory and intellectual means.

The mantra expresses this transcendence through striking imagery. Brahman is unmoving, yet faster than the mind, standing still while surpassing those who pursue it. Within Brahman and by its sustaining power, Mātarīśvan, identified with the cosmic vital force or prāṇa, moves within subtle space and upholds the waters, giving rise to cosmic order and life sustaining processes. Alternatively, this imagery may also signify the animation of prāṇas within the womb, sustaining life even before conscious awareness arises.

Thus, Brahman is revealed as the hidden ground of all activity, the silent presence that enables motion, life, and order, while remaining beyond all direct apprehension.

Note The textual difference between the Kāṇva and the Mādhyandina recensions does not result in any difference in meaning. In the second quarter of the mantra, the term Devas may be understood either as the Divine Beings or as the sense faculties, namely the five senses of perception together with the mind as the sixth. Since these luminous faculties dwell within the individual, the senses are also designated as Devas. The teaching that even the Devas are unable to fathom the mystery of Brahman, and that their powers are derived from Him alone, is illustrated by the well known episode from the Kena Upaniṣad.

In the fourth quarter of the mantra, commentators generally admit both meanings. Mātarīśvan denotes air or the vital life forces, so called because it moves and grows within space, mātari. By extension, the term is also applied to the fetus, which grows within the mother’s womb. The Vedic accent in the mantra indicates that the word apaḥ is plural and refers to atmospheric waters. This interpretation is accepted by Śaṅkarācārya as an alternative meaning and by Raṅgarāmānuja as the primary meaning.

Mantra 5 तदेजति तन्नैजति तद्दूरे तद्वन्तिके । तदन्तरस्य सर्वस्य तदु सर्वस्य बाह्यतः ॥

Translation It moves, and It indeed moves not. It is far and It is near. It is within all this, and It is also indeed outside all this.

Īśāvāsya Upaniṣad 5

Purport Brahman is all pervading and uniform. Therefore, it is immobile and does not travel from one place to another. There is no point where it is not eternally present. Yet, within Brahman, all cosmic bodies, matter, and energies continue to move, creating the appearance of movement attributed to Brahman itself. Because Brahman is omnipresent, it abides in the most remote regions of creation and is at the same time closest to us, as it is present within us. Brahman is immanent, being within everything, and also all pervading and all enveloping, surrounding all beings and existing equally within all.

Notes In Abrahamic religious traditions, God is conceived as dwelling in a remote realm called heaven, from where He governs the world, observes human actions, and communicates through intermediaries. In the Hindu tradition, Brahman is not a distant ruler but an intimate and immediate presence, eternally surrounding all beings and abiding within them, sustaining life, withdrawing it, and witnessing all actions.

Illustrations for Mantras 4–5

1. Elephant and the Six Blind Men

Once, six men who were blind from birth were brought to an elephant and were asked to describe it. They surrounded the elephant and each touched a different part of its body. The first blind man touched the tail of the elephant and declared that the elephant was like a rope. The second touched the leg and asserted that the elephant was like a pillar. The third touched the trunk and said that the elephant resembled a snake. The fourth, who touched the broad body, insisted that the elephant was like a wall. The fifth, who happened to touch an ear, claimed that it was like a fan. The sixth grasped a tusk and confidently proclaimed that the elephant was like a sharp spear. Each of the six men refused to accept the descriptions of the others, firmly believing that his own limited experience revealed the true nature of the elephant.

The moral of the story is that although truth is one, it is described partially from different standpoints. When all perspectives are taken together and harmonized, a more complete understanding emerges. Similarly, those who quarrel over the nature of God resemble these blind men. Their differing views may represent distinct aspects or partial apprehensions of the same truth. Just as the blind men could not perceive the elephant in its entirety, human beings cannot see, hear, taste, touch, or smell the Divine in its fullness. Therefore, dogmatic assertions about the nature of God and the rejection of other perspectives are unwarranted.

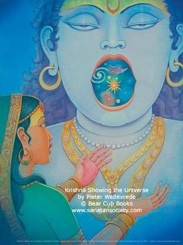

Yaśodā Beholds the Universe in Kṛṣṇa’s Mouth Kṛṣṇa had grown into a young child who could walk and play with other children of his age outside his home. One day, while playing, Kṛṣṇa put some soil into his mouth. One of his companions reported this to Yaśodā. She took Kṛṣṇa by the hand and brought him inside, admonishing him that eating soil was harmful and could lead to illness. She asked him whether he had eaten soil and demanded that he open his mouth to show her.

Kṛṣṇa denied the accusation, but at Yaśodā’s insistence, he opened his mouth wide. Yaśodā was astonished to behold within it the entire universe, including the sun, the moon, the stars, and the earth. She was then convinced that her son was not an ordinary child but the Divine Himself. Perceiving her amazement, Kṛṣṇa employed his divine power to make her forget this realization. Yaśodā resumed her maternal affection, fondling him lovingly, while Kṛṣṇa smiled gently.

These illustrations convey the teaching that the Divine simultaneously transcends and pervades all things, being both beyond complete comprehension and yet intimately present within the world.

Parable When Bāhva was questioned about Brahman by Vāśkalin, he explained it to him through silence. He said, “Learn about Brahman, my friend,” and then remained silent. When questioned a second and a third time about Brahman, he replied, “I am indeed teaching you, but you are not trying to understand. That Ātmā is silence.”

Story: Even Devas Cannot Fathom Brahman

The universe was functioning in its usual orderly manner. In the course of time, the elements of nature, namely earth, water, fire, space, and air, became subtly arrogant. They began to think that they themselves constituted the universe and that they alone were responsible for its existence and maintenance. In order to remove this delusion, Bhagavān resolved to teach them a lesson.

Bhagavān appeared before Fire in the form of a young man. Blinded by pride, none of the elements recognised Him and regarded Him as a stranger from some distant land. Bhagavān addressed Fire and asked him about his powers. Fire replied with confidence that he could burn the entire creation to ashes. Bhagavān then placed a single blade of grass before him and said that he should burn it. Fire exerted itself repeatedly, but the blade of grass did not burn at all. Fire was astonished and shaken.

The other elements were not prepared to abandon their pride. Air stepped forward and declared that he could blow away everything in his path and that he was almighty. Bhagavān placed the same blade of grass before Air and asked him to blow it away. Air made repeated efforts, but was unable to move even that blade of grass. In the same manner, the remaining elements attempted to demonstrate their powers and failed before that mysterious presence.

The five elements were now overcome with fear, for they did not know who this stranger was who had rendered them powerless. They therefore approached their leader Indra, identified with the ātmā, and requested him to investigate. Indra went to the place where the stranger had appeared, but the stranger had vanished. In his place stood a radiant lady named Umā, representing spiritual knowledge.

Indra asked her who the mysterious person was who had humbled the five elements and deprived them of their powers. Umā replied that it was Brahman, the Supreme Being. It is by the will of Bhagavān that the wind blows, the rivers flow, fire burns, space contains all things, and the earth supports living beings. Without the will of that Bhagavān, even a leaf cannot move. The sun rises by His command, the stars shine through Him, and the moon reflects His grace. She instructed Indra to know Bhagavān alone as the source of all power and all properties of the universe, and declared that by knowing Him alone one attains mokṣa.

Story: Brahman is Outside and Within Us The following story from the Śrīmad Bhāgavata Purāṇa, Skandha 12, illustrates through a mystical example how Bhagavān is both within us and outside us.

By the boon of Bhagavān Śiva, the Ṛṣi Mārkaṇḍeya became immortal. Therefore, when the age of the universe came to an end and dissolution began, Ṛṣi Mārkaṇḍeya did not perish. He witnessed a vast cosmic deluge in which waters rose and submerged everything in their path, engulfing all the worlds and all living beings. Distressed by this sight, the sage wondered whether there was anything at all in the universe that was permanent. As the waters continued to rise, he clung to the upper branches of a banyan tree.

At that moment, he saw a single leaf floating upon the turbulent waters below him. Upon the leaf lay a beautiful infant, smiling and sucking his own toe. The child was none other than Kṛṣṇa. Ṛṣi Mārkaṇḍeya rushed towards the child, but as he drew near, he was drawn inside the child by the force of the child’s inhalation. Within the child’s body, an astonishing vision unfolded before him. He beheld innumerable worlds, entire universes, and the continual processes of destruction and creation of universes.

When the child exhaled again, Ṛṣi Mārkaṇḍeya was expelled from the child’s body. He then understood the meaning of what he had witnessed, namely that Bhagavān dwells within creation and that the entire creation also exists within Him. At every moment, countless universes are created within Him, and countless others are dissolved. Everything that can be seen, heard, touched, tasted, or spoken of ultimately perishes, while Bhagavān alone is eternal and imperishable.

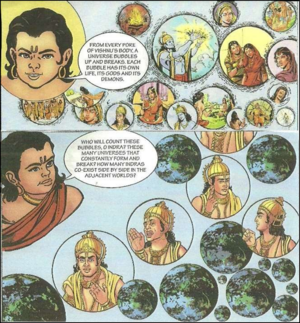

Story: Indra and Many Indras

After Indra defeated the powerful Asura, he faced another task, namely the rebuilding of his capital, Amarāvatī, which had been destroyed in the war. He summoned his architect Viśvakarmā and said, “I am the mighty Indra who has defeated the powerful demon Vṛtra. Build for me a magnificent palace worthy of my greatness, for I am the king of all the Devas.”

In obedience to this command, Viśvakarmā constructed a lofty palace and invited Indra to inspect it. Indra, however, expressed his dissatisfaction, saying that such a structure was beneath his dignity and that something far more grand should be designed and built.

Viśvakarmā redesigned and constructed an even more magnificent palace, whose towers and domes seemed to touch the clouds. Yet Indra remained dissatisfied and demanded something still greater, asking how the mightiest Deva in the universe could live in what he considered an ordinary palace. Though disheartened, Viśvakarmā, fearing Indra, set about creating an even grander structure.

When the day of inauguration arrived, all the Devas marvelled at the beauty, splendour, and opulence of Viśvakarmā’s palace. To their astonishment, Indra was still displeased and reproached Viśvakarmā, accusing him of failing to do justice to Indra’s glory. Unable to bear this any longer, Viśvakarmā approached Bhagavān Brahmā and prayed that Indra’s vanity and pride were boundless, and that despite exhausting all skill and resources, nothing satisfied him. Brahmā replied that they should approach Bhagavān Viṣṇu, who alone could set Indra in his proper place. They went to Viṣṇu, who promised to intervene.

The following day, Indra noticed a group of children playing outside his palace. One child in particular appeared extraordinarily charming and radiant. Indra invited the boy inside and, moved by an instinctive reverence, washed his feet. He then proudly showed the child his latest palace. After observing it carefully, the boy remarked that it was indeed the greatest palace among those in which the Indras before him had lived.

Indra reacted sharply, asking what was meant by Indras before him, asserting that he alone was Indra and that none greater had ever existed. The boy laughed and explained that Indra was merely the ruler of this universe. At any given time, innumerable universes exist, while countless others continuously emerge from and dissolve back into the body of Viṣṇu. Each universe has its own Indra, and during the lifetime of a single universe, many Indras arise one after another. The number of universes and Indras is beyond all counting.

Indra was deeply shaken and protested that such a thing was impossible. The boy then pointed to a stream of ants entering a crack in the palace wall and said that Indra’s finite mind could not comprehend the infinite Viṣṇu and His infinite creations. Each of those ants, he said, had been an Indra in some previous existence. Astonished, Indra questioned how this could be so. The boy replied that one who performs numerous virtuous acts of dharm is reborn as Indra in a heaven within a universe, and after the fruits of those deeds are exhausted, the soul is reborn again as another being. Greatness and insignificance alike arise and pass away, but none exist independently of Viṣṇu.

Indra’s pride was completely shattered. He realised that his vanity was meaningless. Although he had defeated Vṛtra, he was not supreme, and all his power, glory, and fame would eventually fade. Only the Supreme Being endures forever.