Talk:Excessive Reliance on Scriptural Knowledge

By Vishal Agarwal

Knowledge of scriptures is an aid to develop faith and love towards the Divine but is not an end in itself. Swami Ramakrishna Paramahamsa describes this attachment with the help of the following example from our everyday lives:

“A man received a letter from home informing him that certain presents were to be sent to his relatives. The names of the articles were given in the letter. As he was about to go shopping for them, he found that the letter was missing. He began anxiously to search for it, several others joining in the search. For a long time, they continued to search. When at last the letter was discovered, his joy knew no bounds. With great eagerness, he opened the letter and read it. It said that he was to buy five kilograms of sweets, a piece of cloth, and a few other things. Then he did not need the letter anymore, for it had served its purpose. Putting it aside, he went out to buy the things. How long is such a letter necessary? As long as its contents are not known. When the contents are known one proceeds to carry out the directions. In the scriptures, you will find the way to realize Bhagavān. But after getting all the information about the path, you must begin to work. Only then can you attain your goal.”

Swami Abhinava Vidyateertha, the late Acharya of the Shringeri Shankara Matha elaborates how stopping at the study of scriptures without taking the next steps of practice and spiritual experience stunts one’s spiritual growth:

“Shāstra Vāsanā is of three types;

- obsession with study,

- preoccupation with many subjects,

- and marked squeamishness about observances specified in the scripture.

The Taittiriya Brahmana contains a narrative that can serve to illustrate the first kind of Sastra Vasana. Bharadvaja, the Veda says, seriously applied himself to the study of the Vedas for three successive births. In his fourth life too, he wished to strive unremittingly. Taking pity on him, Indra explained the impossibility of learning all the Vedas and then taught Bharadvaja about Brahman with attributes [Traigunya Ishvara]. While Bharadvaja’s study of the Vedas was not wrong, it was his obsession with mastering all the Vedas that was the problem. To get rid of this type of Sastra Vasana, the aspirant should impress upon himself that it is impossible to know a subject in its totality. Addiction to the study of many subjects is also bad. The story of Durvasa encountered in the Kavaseya Gita is pertinent. Durvasa, it is said, once came to the assembly of Bhagavān Mahadeva to pay his respects. He arrived with a cart- a load of books. Narada made fun of him by comparing him to a donkey burdened with a great load on its back. Irritated and cured of his obsession, Durvasa dumped his books into the sea. Thereafter, Mahadeva initiated him into the knowledge of the Atma. One should realize that the Supreme cannot be known by being preoccupied with books on a variety of topics. Thus, the Katha Upanisad declares, “This Atma is not attained through many studies, through the power of grasping the meaning of the texts or through much mere hearing”. Likewise, in the Chandogya Upanisad, we read that despite mastering a wide variety of subjects, Narada was not free from grief as he had not realized the Atma. To attain that sorrow-eradicating knowledge, he approached Sanatkumara as a disciple. It has been said, “What is the point in vainly chewing the filthy rag of talk about sacred treatises? Wise men should, by all means, seek the light of consciousness within”.[1] Sincere practice of scripturally ordained rituals is essential for a person who has not progressed to the stage when he can dispense with rituals. However, undue fastidiousness concerning religious observances, which characterizes the third type of Sastra Vasana, is an impediment. In the Yog Vasista, we encounter the story of Dasura which is relevant here. Dasura, on account of his intense fastidiousness, was unable to locate a single spot in the whole world adequately pure for him to perform his religious rites. Sri Vidyaranya who has elaborately dealt with the destruction of Vasanas in his Jeevanmukti Viveka, points out that Sastra Vasana leads to pride of learning. This is a reason, in addition to the impossibility of consummating the needs of Sastra Vasana, for the Sastra Vasana being labeled as impure.[2]”

The second story included above is given in a more elaborate form below-

Rishi Durvasa and His Pride of Learning Once, a gathering of Rishis took place at Mt Kailash, where Bhagavan Shiva lives. Rishi Durvasa too walked in with a bundle of books in his hand. But he did not greet any of the other Rishis present, and went up to Bhagavan Shiva’s throne, sitting right next to him. Bhagavan Shiva asked him, “Rishi, how is your study progressing?” With pride on his face, Rishi Durvasa replied, “I have studied all the books that I am carrying and have learned them by heart.” Rishi Narada got up and then said, “Pardon me Rishi Durvasa, but you are just carrying these books like a donkey that carries the burden on its back.” When Rishi Durvasa heard these words, he became red with anger, and threatened Rishi Narada, “How dare you ridicule me? I will curse you. Why did you compare me to a donkey?” Rishi Narada replied, “True knowledge gives humility, forgiveness, and good manners. You walked in without greeting others, and sat right next to Bhagavan, instead of sitting at His feet. Does this not show that you have not learned anything even after memorizing your books?” Rishi Durvasa realized that Rishi Narada was telling the truth. He realized that his behavior had been foolish. In repentance, he discarded his books in the ocean and left the assembly to do meditation to atone for his inappropriate behavior.

Story: Bhaja Govindam

One day, Shri Shankaracharya was walking along the banks of the Ganga River in Varanasi with his disciples. He saw a very old Pandit, almost on his deathbed, trying to master and teach the rules of Sanskrit grammar. Out of compassion, the Acharya composed a stotra of 13 verses, in which he asks humans to seek refuge in Krishna because only He can save us at the time of death. Learning rules of grammar for mere intellectual satisfaction will not save us from death. The 14 disciples of Shankaracharya added a verse each, and collectively, it became a Stotra of 27 verses. This beautiful stotra is called Bhaja Govindam, or Moha Mudgara (a Hammer to shatter delusion). The stotra teaches the worthlessness of worldly desires and ego and asks us to seek refuge in Bhagavān by chanting His name, reading the Gita, and becoming dispassionate towards worldly pleasures.

Parāshara Bhattār and Sarvajna Bhatta (12th Cent. CE)

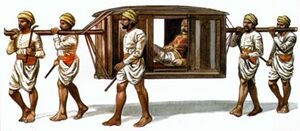

Now, let us learn another story from the life of Parashara to understand the seventh habit of a successful man. The story is from the time when he was a five-year-old child in the temple town of Srirangam in southern India. One day, he saw a grand procession in the honor of a visiting scholar. At the head of the procession was a palanquin lifted by many servants. The scholar arrogantly looked outside from the widow of his palanquin. As the priests of the temples came to meet him, he did not get off the palanquin. He did not even do a Namaskār to them because he was very arrogant and proud of his knowledge and wisdom. He did not even bow to the Murti of Bhargava Vishnu in the Mandir. Everyone around him was heard saying, “What a great scholar this man is! He can answer any question that you can think of.” The little boy Parashara approached the palanquin and asked the scholar, “Sir, I have heard that you can answer any question because you know every holy book. Can you answer my question too? Can you tell me how many grains of sand are in my right fist?”

The scholar was annoyed that a five-year-old kid should stop the procession and ask him such a ridiculous question. He shouted back and said, “Out of my way kiddo! This is not the kind of question that I answer. Why should I care how many grains this worthless sand in your fist has?” The little boy replied, “The fistful of sand that I held had millions of grains of sand. But it was still just a fistful of sand, which is not worth much. Likewise, you might know answers to as many questions as the number of grains. And yet, all your knowledge is like a worthless fistful of sand. The branches of a tree laden with fruit bow, whereas a dry tree with no fruit stands stiff and erect. Likewise, a man who is truly great, wise, and knowledgeable becomes humble. He bows to Bhagavān and takes care to follow Dharm. Faith in Dharm and Devotion to Bhagavān alone is what makes one truly great and successful.”

The scholar was very impressed with the little boy’s response. He got off the palanquin, lifted the child, and carried him on his shoulders to meet with and offer respects to his parents, who had given birth to such a wonderful boy and taught him that the secret to being truly successful is having faith in Dharm and Bhagavān.

Story: Madhusūdana Sarasvati The Learned Scholar who learned the value of Devotion Madhusudana Saraswati was a very renounced scholar of the 17th century. He was born in what is today Bangladesh and lived in Bengal and Varanasi, where he wrote his famous works like the commentary on the Bhagavad Gita. He also organized the ascetic orders of Dashnami Sannyasins and opened some of these orders to women and Shudras for admission. A beautiful story is narrated on how he forsook his ego and merged it with Krishna, melting his pride in the love for Krishna[3].

One day, he was busy writing his classic on Advaita Vedanta called the ‘Advaita Siddhi’. Suddenly, a monk entered his study room and rudely sat on a very high pedestal in front of him. Madhusudana Saraswati was taken aback but immediately upon sitting, the Sadhu asked Madhusudana Saraswati – “Tell me truthfully. During a philosophical debate with another scholar, do you feel agitated in your mind when you are not able to refute or respond to your opponent’s arguments?” “Yes,” said Madhusudana Saraswati.

The Sadhu then asked, “And when you defeat an opponent, do you feel euphoric?” “Yes,” replied Madhusudana Saraswati again. The Sadhu smiled and said, “You have not shed your ego to the extent that you should have. I recommend that you worship Krishna. Over time, you will lose your ego, merge in Krishna, and experience a joy that you cannot get even if you defeat the greatest scholar on this earth in a debate. You are a great scholar of Advaita Vedanta, but you will get the fruit of your wisdom if you have devotion for Krishna.” Then, the Sadhu instructed Madhusudana Saraswati in the 8-syllable mantra on Krishna and left.

Madhusudana Saraswati chanted the mantra for six months with the correct procedure but he saw no result. So he repeated his religious vow for another six months. But Krishna did not appear to him even in his dreams. Despairing, Madhusudana Saraswati thought, ‘What a fool I was to have abandoned my profound study of Advaita Vedanta for the sake of this useless chanting and prayer.”

He left Varanasi and went to Kapildhara – a sacred waterfall close to Amarkantak on the Narmada river in central India. One day, a cobbler (the profession of a cobbler was considered a lowly profession in those days) came to him and said, ‘Swami-ji, looks like you have no patience or persistence. You gave up your search for Krishna in a mere twelve months, whereas even the less knowledgeable people spend their entire lifetime in His search.” Madhusudana Saraswati was greatly humbled. “How could this cobbler know what I have been doing in the last year?” he thought. He asked the cobbler, “How did you find out that I gave up my search for Krishna in a mere 12 months?”

The cobbler replied, “I have pleased a ghost, who tells me secret information about others.” Madhusudana Saraswati replied, “I have not been able to see Krishna. Perhaps, you can teach me how to see your ghost. I am willing to humble myself and see that unclean ghost, because he may be able to take me to Krishna.” The cobbler told him the correct procedure to propitiate the ghost. Madhusudana Saraswati now started worshipping the ghost, but when he did not appear even after three days of non-stop prayer, the ascetic got angry. Now he, a scholar, walked himself to the hut of the humble cobbler and asked him why the ghost had not appeared.

The cobbler replied, “My mantra is effective and true indeed. But the ghost is scared to appear in front of you. He says that you have chanted the Gayatri mantra for many years, then the Vedas for a long time. And finally, the mantra of Krishna for a year. All this has made you very powerful. If the ghost appears in front of you, he will get incinerated immediately, and therefore he dare not come to you. The ghost says that you need to have more persistence and patience. Chant the same mantra of Krishna with devotion and faith for six more months, and you will see a magnificent result.” Madhusudana Saraswati was chastened, and he did as the ghost had said. And after six months, when his ego had melted away, and his heart had been filled with the love of Krishna, he had a Divine vision. Moved by this vision, Madhusudana Saraswati then wrote his masterpiece, ‘Bhakti-rasāyana’ (The Alchemy of Devotion), a famous treatise on the path of Bhakti.

References[edit]

- ↑ Adiswarananda, Swami. The Four Yogas. Skylight Paths Publishing, Woodstock, Vermont, p. 139. (Quoted with slight modification.

- ↑ A Disciple. Enlightening Expositions: Philosophical Expositions of Sringeri Jagadguru Sri Abhinava Vidyatheertha Mahaswamigal. Sri Vidyateertha Foundation, 2009, pp. 43–45.

- ↑ Sarasvati, Swami Akhandananda. Narada Bhakti Darshana. Satsahitya Prakashan, 1966, pp. 15–16.