Talk:Implications of the Doctrine of Rebirth

By Vishal Agarwal

The conviction that we are reborn upon death and that our perishable body is merely a temporary garment or house that is replaced by another in the next life has many implications.

The first is that we become more accepting of death as a fact of life. We may of course grieve at the death of a loved one, but not excessively.

The wise people do not grieve excessively over those whose life breath is gone or those who are living. Gita 2.11cd

Story: Ma Sharada Devi feels the constant presence of Swami Ramakrishna Paramahamsa after his Death

“In 1885, Ramakrishna developed cancer of the throat and steadily grew worse. On August 15 of the following year, realizing his end was near, Ramakrishna assured his wife, Sharada Devi, that she would be all right and that his young disciples would care for her as they had of him. He died the next day. In his last days, he addressed himself saying, “O mind, do not worry about the body. Let the body and its pain take care of each other. Think of the Holy Mother [Sharada Devi] and be happy.

After the cremation of his body, Sharada was removing her jewelry, as widows do, when Ramakrishna appeared to her. In the vision, he told her not to remove her jewelry, assuring her that he had not gone away but had only passed from one room to another. Confident of his continual presence with her, the Holy Mother, as she was known to her devotees, committed herself to teaching and guiding the young disciples who had been left in her care.”

The second implication is the awareness that the only constant in life is change, and death is also one such change that the eternal, changeless ātmā experiences. All these ‘changes’ pertain only to the body and not the ātmā.

Just as the embodied (ātmā) within this body goes through childhood, tough, and old age; in the same way, it takes on another body (after death). Therefore, the firm and wise person is not deluded by this. Gita 2.13

Our entire life is transitory, like a dream. To the eternal reality of the ātmā, our bodily existence is temporary and false.

The Dream of King Janaka: A beautiful story is narrated traditionally to demonstrate that relative to eternity of our ātmā, even our entire physical life in a body is inconsequential and unreal-

“His Majesty King Janaka, the ruler of Mithila, once had a dream. In his dream, he was a starving beggar. For seven days he had gone without food. He went to Delhi and begged, “Please, will someone give me a morsel to eat?” He had no money. He asked if there was an almshouse nearby. “Yes, there’s one where they give free rice to eat,” someone guided him.

He found the almshouse but the man in charge was quick-tempered. He ordered, “Bring your bowl for food.” King Janaka had nothing with him and so searched for a potter. After a while, he came to a potter’s house but he abused him with foul language and closed his doors. Hopeless and depressed, Janaka turned to the garbage heaps, looked through litter, and found a broken clay vessel. He got his share of food and moved to a small corner to sit and quietly eat. Just then, two bulls which had run loose, came near him and started a furious duel. Scared, Janaka got up, and as he tried to save himself, his portion of food fell. He was shocked and paralyzed with fear.

Just then his eyes opened. The dream abruptly ended. He shook himself out of his sleep and heard his guards sound the trumpets and call, ‘Victory to His majesty, the noble king of the city of Mithila.”

He was in his richly ornamented bed in his royal bedroom. He was lost in deep thought, “Which is real? The dream or this kingdom?” He approached his guru Aṣhṭāvakra. “O Guruji, in my dream I could not even eat a morsel, such was my fear, and now I walk supreme as a king. Which is real out of the two?”

Aṣhṭāvakra replied, “Neither! Even this life is a dream. That was a short dream and this life is perhaps a sixty, seventy, or eighty-year-long dream!” The things of this world are short-lived, only temporary.”

Third, just as death is inevitable for creatures, so is rebirth inevitable for the dead (unless they attain Moksha). In their next life, they might not be present with us in the form and through the relationship we had known them, but they manifest in another form unknown to us. This may be explained with the example of passengers traveling in a train. At every station, some passengers alight, others depart. Each passenger has different co-passengers sitting next to him from time to time during his journey. He talks to these different passengers and shares food with them. The co-passengers had never met before they came together on the train and may not get together again after they depart. This world is also similar – we come together for some time and then depart. We do not know where our relatives and friends were before this life, and where they will be after their current life.

Death is indeed certain for those who are born, and rebirth is certain for the dead. Therefore, over the inevitable, you should not grieve. Gita 2.27

What we call life, is a manifestation of the formless ātmā in a physical form. Over multiple lifetimes, the ātmā passes through a series of non-manifest and manifest states alternately. The Gita says-

Bhārata, beings are un-manifest in their beginning, manifest in their middle, and then un-manifest again in their end. Then, what is there in this for lamentation? Gita 2.28

For this reason, it is important not to get excessively attached to our loved ones. And when they die, we must not grieve excessively and should rather focus on acting in ways that smoothen the onward journey of the departed. The following story illustrates this teaching-

Chitraketu’s son refuses to become ‘alive’: The Bhāgavata Purāṇa narrates the following story -

Although King Chitraketu had many queens, none of them bore him a child. He was very depressed and worried about who would become the next king after him. Fortunately, due to the blessings of Rishi Angirasa, one of his queens gave birth to a Prince. The King was overjoyed. However, the other queens became very jealous. They were worried that the Prince’s mother would henceforth become the Chief Queen and the favorite of the King. Therefore, they conspired together and poisoned the infant Prince to death.

King Chitraketu’s grief knew no bounds, and he lamented over the dead body of his son. Rishi Angirasa happened to stop by along with Rishi Nārada. The King served him with respect and begged the Rishi, “Respected Sir, through your spiritual powers, you can bring my dead son back to life. I beg you, please revive him. He is the greatest joy of my life, the heir to my kingdom.”

Rishi Angirasa tried to explain to the King, ‘Everyone who is born has to die one day. Some die at an old age, some die young. It is against the rules of nature to revive a dead person. Let go of your attachments and accept the reality of death, no matter how dear your son is to you.” Rishi Nārada also counseled him saying, “This world is like an ocean and we humans are like the infinite number of sand grains on its shore. Two grains come together for some time, only to be separated by waves eventually. And these same two grains might come together again in the future. Dear King, accept this fact of life – that all relationships eventually come to an end.” But King Chitraketu and his Queen would not let go of their grief, and they begged piteously again and again. Out of compassion, Rishi Nārada revived the dead boy. King Chitraketu and his Queen were overjoyed. But a surprise awaited them.

The boy spoke to his parents like a spiritually realized adult. He said, “I did not go anywhere. When I left my body, I recollected all of my past lives through the grace of Rishi Angirasa. I have lived in many bodies before this one. I have had many fathers and many mothers. Therefore, who is my real father, and who is my real mother? I have never died, and I was never born. It was merely my body that died and took birth. I performed numerous karms in each life and was reborn to reap the results of my deeds. I have realized that I am, in reality, the eternal, unchanging, pure, and free Atman.”

Saying this, the boy died once again, because he did not want to get attached to his parents. King Chitraketu and his Queen understood the purpose of their son’s words. Their attachments disappeared when they realized that all relationships were temporary and end one day. It is only our soul that is permanent. The only permanent relationship that we have is with the Divine, and He is our goal. Swami Sivananda explains the principle of this story with the help of another example from our daily lives:

“Life is like a manuscript, and each person is an author of that manuscript. In this manuscript of life, some of the pages are missing – the beginning and end have been misplaced, and one cannot recollect what he has written in them. He has only the middle portion with him, and that portion tells what he is in this present life. He knows he is here, but he does not know from where he has come, why he has come, or where he will go.”

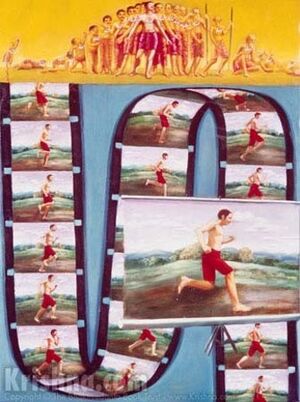

Another analogy is that our successive lives are like individual frames in a continuous reel of film that depicts a story without a beginning or an end (unless Moksha is achieved). Funeral ceremonies are therefore focused on enabling the departed ātmā to sever its attachment to the loved ones it has left behind and take rebirth into a better state (than its past physical life) or better still – attain Moksha.

Some other implications of the model of Ātmagati – or the journey of ātmā upon physical death are:

- First, it is an extremely comprehensive model that weaves all living creatures in the wheel of Samsāra (births and rebirths). It accounts for the phenomenon of ghosts and also includes the notions of Heavens and Hells.

- The second noteworthy feature of this model, which contrasts it with Abrahamic notions, is that there isn’t just one heaven and one hell – rather, there are many enumerated in Dharmic traditions.

- Furthermore, the Dharmic heaven and hell are not permanent post-death abodes of any ātmā; it is only temporary abodes. This is why Śāstras emphasize that we must not aspire merely to reach heaven. Heaven is not our final goal. The Deva-s (‘gods’) dwelling in heaven can get too attached to the pleasures of their world, and this can lead to their spiritual downfall. For this reason, the Śāstras delight in narrating stories of Indra and other residents of heaven, such as Nahuṣa, becoming arrogant, undisciplined, and hedonistic, and eventually being reborn as lower life forms.