Talk:Knowledge of Sanskrit and Scriptural Learning

By Vishal Agarwal

Most of the core sacred literature is composed in the Vedic and Sanskrit languages that have not been understood by the masses for several centuries. To take the egalitarian message of Bhakti to these masses, our Saints and Bhaktas have composed devotional literature in the vernaculars. Even Sanskritic texts declare that one can communicate spiritual teachings in languages other than Sanskrit as well –

He is a Guru, who enlightens his student not through the medium of Sanskrit or Prākṛta alone, but even through the medium of the local vernaculars which the student understands as his mother tongue. Śivadharmottara Upapurāṇa 2.3

Below are a few examples from the Bhakti tradition to illustrate this fact –

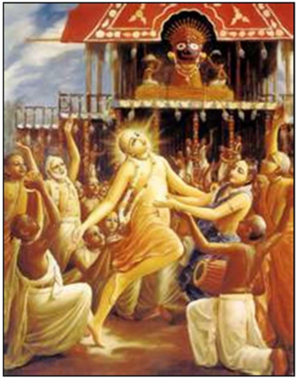

Story – Caitanya Mahāprabhu and the Illiterate Brāhmaṇa

While touring South India, Caitanya encountered a certain Brāhmaṇa in the temple of Raṅgakṣetra. This man daily sat in the temple turning over the pages of the Bhagavadgītā, but his constant mispronunciation of the Sanskrit made him the object of general mirth and derision. Caitanya, however, observed signs of genuine spiritual ecstasy on the Brāhmaṇa’s body, and he asked him what he read in the Gītā to induce such ecstasy. The Brāhmaṇa replied that he didn’t read anything. He was illiterate and could not understand Sanskrit. Nevertheless, his Guru had ordered him to read the Gītā daily, and he complied as best he could. He simply pictured Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna together on the chariot, and this image of Kṛṣṇa’s merciful dealings with his devotee caused this ecstasy. Caitanya embraced the Brāhmaṇa and declared that he was an authority on reading the Bhagavadgītā.[1]

Pūnthānam Pūnthānam Nampūtiri (1547–1640 CE), although born in a family of the learned Nampūtiri Brāhmaṇas of Kerala, was not very educated. He and his wife did not have any child for a long time. Therefore, they prayed to Bhagavān Kṛṣṇa at the Guruvāyūrappan temple in northern Kerala and were blessed with a baby boy. Their joy knew no bounds, and the couple soon organized the annaprāśana (first feeding of solid food) ceremony for their son.

Unfortunately, a guest accidentally threw his shawl over the baby, who was sleeping in the corner of a room on the floor. Other guests too blindly did the same. Tragically, the baby was suffocated to death. Pūnthānam and his wife were greatly grieved, and Pūnthānam sought solace by worshipping Kṛṣṇa in the Guruvāyūrappan Maṇḍira, imagining Kṛṣṇa Himself as his baby. In a mood of great sorrow, he composed a beautiful poem called the Jñānappāna, in which he expresses his great Bhakti for Kṛṣṇa. A line in the poem reads, When the baby Kṛṣṇa plays in one’s mind, does one need any biological children? This poem is in the Malayalam language which is spoken in Kerala.

Residing in the same Maṇḍira was Melpathūr Nārāyaṇa Bhaṭṭatiri, a renowned scholar of Sanskrit who composed the immortal Sanskrit classic called Nārāyaṇīyam in praise of Bhagavān Viṣṇu. Pūnthānam humbly approached Bhaṭṭatiri with the request, “Sir, you are a great scholar. Please go through my poem and let me know if I should correct any mistakes in it.” But Bhaṭṭatiri responded arrogantly, “Why should I review a poem in the Malayalam language which is spoken by the common people? Plus, your poem will have many mistakes anyway, because you are not very educated.”

When Pūnthānam heard this answer, he was greatly saddened. He burst into tears. Bhagavān Kṛṣṇa could not bear the fact that Bhaṭṭatiri, although a great scholar, had insulted His humble Bhakta Pūnthānam. And miraculously, a voice from the mūrti said, “Pūnthānam is perhaps not as strong as you in vibhakti (grammatical declensions in Sanskrit), but he is greatly superior to you in Bhakti. I prefer his Malayalam poem Jñānappāna over your Sanskrit work Nārāyaṇīyam.”

The command of Kṛṣṇa greatly shook Bhaṭṭatiri. He rushed to Pūnthānam and begged for forgiveness. When Bhaṭṭatiri read the Jñānappāna, he was moved and impressed by how profound the sentiments of the poem were. Bhaṭṭatiri then incorporated some ideas from the Malayalam poem in his own Sanskrit work! Today, the Jñānappāna, due to its great esteem and popularity in Kerala, is considered the Bhagavadgītā of Kerala. This poem is renowned for the fact that it explains the deep philosophy of Hindu Dharma in a very easy-to-understand manner in a language that is spoken by the common man.

The incident of Kṛṣṇa preferring Jñānappāna over Nārāyaṇīyam also demonstrates the fact that Bhagavān does not care about the language used by His Bhakta, as long as that language is full of love and devotion for Him.

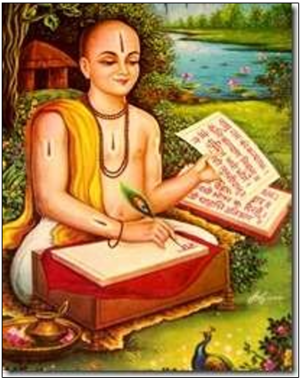

The Lord’s Language: Tulasīdāsa Writes His Rāmāyaṇa in Hindi

Many people think that Dharm can be taught only in its original language Sanskrit and only through the explanations of great Saints and Sages. However, the story of Tulasīdāsa below shows that given the ignorance of the common man, we should simplify the teachings of our scriptures, and teach them in a language that they can understand, be it English, Hindi, Tamil, etc.

Sant Tulasīdāsa is considered an incarnation of Sage Vālmīki in our modern times. Tulasīdāsa noted that India at that time was ruled by foreign Muslim rulers who were very harsh on the Hindus. Temples had been demolished, scriptures burned, people forced to convert. Tulasīdāsa decided to teach the Rāmāyaṇa to everyone, because it describes the life story of Lord Rāma, the ideal king, son, and devotee. But the original Rāmāyaṇa by Vālmīki was too long and in Sanskrit.

He initially began composing a shorter Sanskrit version, writing a few verses daily. But each night, the paper would mysteriously become blank. Eventually, Lord Śiva appeared in a dream and told him, “Tulasīdāsa, write your Rāmāyaṇa in the Awadhi language so that common people may benefit.” He obeyed and began composing the Rāmacaritamānasa, meaning “The Holy Lake of the Acts of Rāma.” Teaching it in Vārāṇasī, he attracted thousands.

Because it was written in Awadhi, a form of Hindi, the common people understood it and felt deep devotion. However, some local Paṇḍitas objected, claiming only Sanskrit scriptures were authentic. They placed his manuscript in the Kāśī Viśvanātha temple beneath the four Vedas. The next morning, it was miraculously on top, inscribed with the words Satyam Śivam Sundaram—Śiva’s divine endorsement.

Ashamed, the Paṇḍitas apologized, and Tulasīdāsa’s work was celebrated everywhere. People began singing the Rāmacaritamānasa across India. Though not in Sanskrit, Śiva deemed it equal to the Vedas, showing that any language filled with sincere Bhakti is accepted by the divine.

Story: Vāmana Paṇḍita Switches from Sanskrit to Marathi

The story of Vāmana Paṇḍita shows how mere scriptural knowledge is not enough. Only when our ego is removed and our hearts filled with Bhakti and compassion for common people does knowledge become spiritually fruitful.

Born in a Brāhmaṇa family in Bījāpura under Muslim rule, young Vāmana was a Sanskrit prodigy. Offered patronage to convert to Islam, his family instead sent him to Vārāṇasī to study. After 20 years, he became a master debater. Hearing of Rāmadāsa, he challenged him to a debate. But waiting all night, he overheard ghosts predicting his spiritual downfall due to pride. Shocked, he realized the truth and sought Rāmadāsa’s guidance.

Rāmadāsa advised intense meditation on Viṣṇu at Badarikāśrama. Later, after divine darśana, he was told to meditate on Śiva at Śrīśaila. After years of practice and visions, Rāmadāsa finally instructed him to write in Marathi so that ordinary people could benefit. Until then, his works were limited to scholars. He complied and authored several poems and a famous Marathi Bhagavadgītā commentary titled Yathārtha Dīpikā.[2]