Talk:Shāstradriṣhṭi – Reads Scriptures with Full Faith and Devotion

The Bhakta Yogī focuses on reading the beautiful narratives of the Lord and never tires of or satiated by hearing them. Every incident reminds him of some parallel or anecdote in the scriptures. Every object reminds him of the Lord. And he reads or listens to the scriptures not mechanically but with full devotion. The following stories illustrate this quality of the Bhakta Yogī.

Live the Scripture, not just Study it:

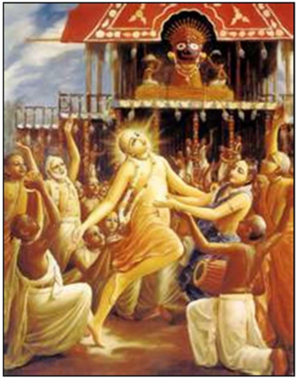

Studying the Bhagavad Gita is not an end in itself. Once, a man came to Swami Chinmayananda and said, “I have gone through the Gita fifteen times.” Swami-ji asked, “But has the Gita gone through you even once?” The story below illustrates this message very aptly- “While touring South India, Chaitanya encountered a certain Brahmin in the temple of Rangakshetra. This man daily sat in the temple turning over the pages of the Bhagavad-gita, but his constant mispronunciation of the Sanskrit made him the object of general mirth and derision. Chaitanya, however, observed signs of genuine spiritual ecstasy on the brahmin’s body, and he asked him what he read in the Gita to induce such ecstasy. The brahmin replied that he didn’t read anything. He was illiterate and could not understand Sanskrit. Nevertheless, his guru had ordered him to read the Gita daily, and he complied as best he could. He simply pictured Krishna and Arjuna together on the chariot, and this image of Krishna’s merciful dealings with his devotee caused this ecstasy. Chaitanya embraced the Brahmin and declared that he was an “authority on reading the Bhagavad-gita[1].””

Another time, during his South India tour, a group of young boys got very attracted to Chaitanya’s chanting of Krishna’s names. They started following him, chanting ‘Hari, Hari.’ When the father of one of the boys saw this, he was very angry. He started beating Chaitanya Mahāprabhu and said, “You are mad man, and you are now trying to make madmen out of these kids too.” Chaitanya Mahaprabhu said, “You may beat me as much as you want. But please do not stop these little children from chanting the names of Krishna.”

King Kulashekhara Alvār Orders His Army to Help Shri Rama

It is said that Kulashekhara Alwar, the saintly king of Kerala in the 8th9th cent., was one day listening to this section of the Ramayana in which Bhagavān Rama was gathering the army of ill-equipped and poor Vānaras to fight the powerful and rich king of Sri Lanka. For the King, the Ramayana was not an ancient historical story, but something that was happening in front of his own eyes because he listened to the Ramayana with his full heart in it.

He got so excited that he ordered, “What a shame that my Lord Rama should have to rely on the Vānaras who are short of armor and weapons, and here I am ruling a kingdom. I order my army to get ready and march towards Lanka to support Lord Rama and rescue Sita.” The ministers got scared when they heard the command of their King, and it was with great intelligence and tact that they were able to convince him to withdraw his command. They pretended that Rama had sent a message himself to the King that he no longer needed Kulashekhara’s help because Ravana had been defeated.

King Kulashekhara is regarded as one of the 12 greatest Vaishnava saints of southern India. He himself wrote many sacred hymns in Sanskrit as well as in a language named Maṇipravalā (a mixture of Tamil and Sanskrit) that are still sung by Hindus with great devotion.

References[edit]

- ↑ Rosen, Steven. The Life and Times of Lord Chaitanya. Folk Books, 1988, pp. 163–164. Brooklyn, New York.