Talk:Superiority of Bhakti Yog is Declared in the Scriptures

By Vishal Agarwal

According to some texts, the superiority of the path of bhakti over those of karm-yog and jñān-yog is self-evident because it is said so in the scriptures.

Kṛṣṇa said: "The yogī is superior to the ascetics, he is thought to be superior to the learned. And the yogī is also superior to those who perform ritual karms. Therefore, be a yogī, Arjuna.Gītā 6.46" "Moreover, of all these yogīs, he whose inner ātman abides in Me, and who worships Me, full of faith—him I consider to be the most devoted to Me in yog.Gītā 6.47" "Devotion is indeed the most superior because of the declaration (in the Gītā) that the devotee is superior to the performers of yajñas, the followers of jñāna-yog as also those who practice austerities.Śāṇḍilya Bhakti Sūtra 22"

The following story, among many others, is cited on the superiority of a bhakta over the yogī:

Story: Jñāneśvara and Yogī Cāṅgadeva[edit]

Yogī Cāṅgadeva had lived a long life of 1400 years due to his practice of intense yogic exercises. But his mind was still full of ego and pride. One day, he heard that a sixteen-year-old saint named Jñāneśvara was in his area, along with his two other saintly brothers and a saintly younger sister named Muktābāī.

He wanted to meet them, intending to make them his disciples. But he wondered, "How shall I invite them? I do not want to address them as 'Respected Jñāneśvara' because that would mean that I am inferior to him. Nor do I want to address him as 'Cirañjīvī' (long-lived), because I am almost 100 times older than him." Thinking thus, he sent a blank piece of paper as an invitation through one of his students.

When Jñāneśvara saw the blank paper, he smiled. His sister Muktābāī understood that Cāṅgadeva's pride prevented him from writing an appropriate invitation. She remarked, "Your guru may have lived 1400 years, but I am sorry to say that his life is as blank as this piece of paper."

Sant Jñāneśvara then wrote the message of spirituality in 65 Marathi verses on that piece of paper. He titled these verses Cāṅgadeva Praśasti ("In Praise of Cāṅgadeva"), which are considered a holy book even today.

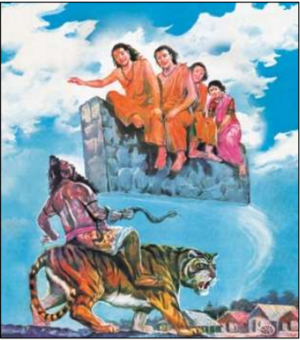

When the message reached Cāṅgadeva, he was livid with anger as well as pride. Moreover, he was unable to understand the verses at all. Determined to teach the four teenagers a lesson, he summoned a tiger to become his mount and took a snake as a whip in his hand. Onlookers marveled at Cāṅgadeva's command over the animals as he rode the tiger toward the place where the four siblings were staying.

When Jñāneśvara received advance news of Cāṅgadeva’s arrival riding a tiger and wielding a snake, he was disappointed by Cāṅgadeva’s pride. At that time, the siblings were sitting on a wall. Sant Jñāneśvara commanded the wall to fly toward Cāṅgadeva.

Seeing the wall flying toward him with the four saints seated on it, Cāṅgadeva was awestruck. He dismounted the tiger and bowed before the Sant, saying, "You are surely greater than I am. I can command living creatures, but even inanimate things obey your command." He became a disciple of Sant Jñāneśvara, who humbly asked him to become a student of Muktābāī instead.

The wall that flew at Jñāneśvara’s request still exists and is worshipped by in Vārkarī tradition. There are also several temples dedicated to Cāṅgadeva in that region, honored due to his association with Sant Jñāneśvara.

Story: Yogī Gorakhnātha is Humbled by Bhakta Allama Mahāprabhu[edit]

Numerous miracles are attributed to Gorakhnātha. Once, he made a clay toy for a child and brought it to life. On another occasion, he turned a part of a hill into gold and then reverted it. At the Kumbha Melā on the Godāvarī River, he miraculously produced large amounts of food, feeding thousands of pilgrims. Another time, he reduced his body to ashes and then revived it. He was also capable of aerial travel.

In many stories, it is narrated how Gorakhnātha, despite his powers, occasionally fell into the traps of dhyāna-yog and had to be humbled. One such story is as follows:

"Gorakṣa, the leader of the Siddhas, had a magical body, invulnerable as a diamond. Allama mocked his body and his vanity. Legend says that he gave Allama a sword and invited him to try cutting his body in two. Allama swung the sword, but it clanged on Gorakṣa's diamond body; not a hair was severed. Gorakṣa laughed in pride. Allamaprabhu returned the sword, saying, 'Try it on me now.' Gorakṣa came at Allama with all his strength. The sword swished through Allama’s body as if it were mere space. Such were Allama's powers of self-emptying—his ‘achievement of Nothingness.’ Gorakṣa was stunned. He realized the contrast between his own diamond-hard body—materially perfect but spiritually limited—and Allama's body of spirit. This revelation was the beginning of his enlightenment."

Allama said to him:

With your alchemies, you achieve metals but no essence. With all your manifold yogs, you achieve a body but no spirit. With your speeches and arguments, you build chains of words but cannot define the spirit. If you say ‘You and I are one,’ You were me, But I was not you. [1]

References[edit]

- ↑ Ramanujan, A. K. Speaking of Śiva. Penguin Books, 1973, pp. 146–147.