Talk:The Creation is a Part of Īshvara and Contained within Him

By Sri Vishal Agarwal

In contrast to Abrahamic traditions, where God is viewed as external to and above creation, Hindu dharm emphasizes that nothing exists outside the Supreme Being. All existence is considered to be within and part of the Supreme Reality.

The Ṛgveda raises a fundamental inquiry into the origin of creation: what was the original and material cause by which the creator, who envisioned this universe, fashioned the earth and the heavens? It asks what tree or forest served as the source of this creation, and upon what support the worlds rest (Ṛgveda 10.81.2,4).

The Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa of the Yajurveda responds by declaring that Brahman is both the forest and the tree from which the earth and heavens were formed. It affirms that Brahman alone existed and sustains all worlds (Yajurveda, Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa 2.8.9.6).

The Chūlikā Upaniṣad of the Atharvaveda describes Brahman as the principle in which the universe is interwoven, whether moving or motionless. Just as bubbles arise and dissolve in the ocean, beings emerge, disappear, and reappear in Brahman.[1]

Philosophical Interpretation

A modern interpretation explains that this perspective regards Brahman not as a personal deity with attributes, but as the principle underlying all existence. Brahman is the Ultimate Reality manifesting as everything—galaxies, living and non-living entities, as well as mental and intellectual faculties. The universe is thus viewed as sṛṣṭi (projection) of this principle, paralleling the scientific search for unity behind all phenomena.[2]

The same author clarifies that Hindu thought does not equate the universe with Bhagavān, which would amount to pantheism. Instead, Bhagavān or the Ultimate Reality manifests as the universe. Within this manifestation, living beings hold a special position, as Brahman is more fully expressed in them. This understanding introduces the related concept of ātmā (self or inner essence).[3]

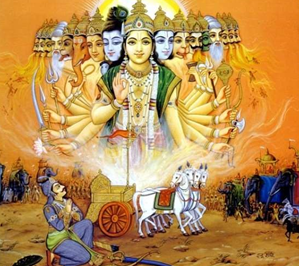

Arjuna’s Vision of the Viśvarūpa (Bhagavad Gītā, Chapter XI)

After Kṛṣṇa had explained the nature of Bhagavān and His divine manifestations, Arjuna requested to see the Universal Form. He asked that if he was deemed worthy, he should be granted the vision of the Divine Form.

Kṛṣṇa responded that ordinarily no one can see this form, but as Arjuna was His companion, He would bestow divine sight. With that vision, Arjuna beheld the Viśvarūpa (Universal Form): a being with countless faces and eyes, adorned with celestial ornaments, garments, and garlands, radiating a brilliance greater than a thousand suns. Within this vision, Arjuna perceived the entire universe—past, present, and future.

Overwhelmed, Arjuna bowed and described what he witnessed. He declared that within the form he could see Brahmā, Viṣṇu, Śiva, the heavens, the earth, planets, stars, and all beings. He described the radiance as dazzling and infinite, without beginning, middle, or end, sustaining dharm eternally. He noted the terrifying sight of blazing mouths into which the warriors of Kurukṣetra were seen plunging like moths into flames, symbolizing the inevitability of destiny. Arjuna, both awed and fearful, pleaded to again behold the familiar four-armed form of Viṣṇu.

Kṛṣṇa then resumed His Viṣṇu form and explained that such a vision cannot be attained merely by study, ritual, or austerity. It is through devotion (bhakti) that this form becomes accessible. He instructed Arjuna to act as His instrument, as the outcome of the battle was already ordained. The vision conveyed that all space and time—past, present, and future—are contained within Bhagavān, who is infinite, the creator, sustainer, and destroyer of the universe.

References[edit]

- ↑ Bedekar, V. M., and G. B. Palsule. Sixty Upanishads of the Veda. Vol. II, English translation of a German translation by Paul Deussen. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited, 1995, p. 222.

- ↑ Lakhani, Sita. Hinduism for Schools. London (UK): Vivekananda Centre, 2005, p. 21.

- ↑ Lakhani, Sita. Hinduism for Schools. London (UK): Vivekananda Centre, 2005, p. 21.