Talk:The Mechanics of Voluntary Karm (Puruṣhakāra Karm)

By Vishal Agarwal

Now we can summarize how puruṣakāra karm (voluntary action) is performed in a more precise manner.

The knower (jñātā), knowledge (jñāna) and the object of knowledge (jñeya) – these three motivate action. Even so the doer (kartā), the organs (karaṇa) and activity (karm) – these are the three constituents of action. — Gītā 18.18

There are threefold instigators of karm. First, the manas generates the thought. Then, the buddhi takes a decision (and results in the action). And finally the heart (the ātman seated in the heart) has pleasurable and non-pleasurable experiences (due to the actions taken). — Mahābhārata 12.248.1

In light of the above verses and the preceding sections, puruṣakāra karm (voluntary action) is completed in the following steps:

1. Object of Knowledge (jñeya): First, a cognition (through one of the sense organs) or a thought (new or recalled from memory or arising in a dream) arises in the manas (mind).

2. Knowledge (jñānaṃ): This object of knowledge is presented to the buddhi and is interpreted by it through the filter of five karmayonis. This interpretation results in the formation of ‘knowledge’ and leads to a decision on the action. The Bhagavad Gītā gives a tripartite classification of jñāna to emphasize the choice of the sāttvika variety:

The jñāna by which one sees the One Imperishable Being in all beings, undivided in separate beings – know that jñāna to be sāttvika.Gītā 18.20

The jñāna which sees in all beings separate entities of various kinds due to their differentiation – know that jñāna to be rājasa. Gītā 18.21

But that jñāna which is attached to a single effect as if it were whole, without concern for the (real) cause, without grasping the real truth, and trivial – that jñāna is declared to be tāmasa.Gītā 18.22

3. Desire and Resolve (karmayoni and saṃkalpa): The object, interpreted by the buddhi, creates a motivation or desire (karmayoni) about the necessity of performing the action (saṃkalpa). The decision of the buddhi may be influenced by the citta (reservoir of vāsanā-s), ahaṃkāra, and the senses (indriya) through the manas, but the final resolution (niścaya) belongs to the buddhi.

As described:

“The manas also collects and organizes data from ahaṃkāra. Information from the ahaṃkāra can be valid and useful, but its inherent bias must be taken into account... The individual consciousness of ego is born when an infant begins to view existence exclusively in terms of subject and object. This limited “I” perceives every object or relationship as either pleasant or unpleasant. Left undisciplined, the unruly ahaṃkāra continually reinforces a human being’s alienation from the One Absolute Reality.” [1]

“As the manas debates whether or not to take an action, information retrieved from the unconscious portion of the mind (citta) is added to the various suggestions of the ahaṃkāra and senses. The citta is analogous to a computer’s hard drive – a reservoir of all your saṃskāra-s and the storehouse of information defined as useful in fulfilling your desires.”[2]

“The buddhi is the only function of the mind that has the competence to discriminate and decide. It has the potential for great wisdom. However, without sufficient exercise and purification through sādhanā, the buddhi may reflect the limited perspective of the senses, ahaṃkāra and citta instead of the wisdom of the superconscious mind. This is a perfect example of the ‘squeaky wheel’ theory. Sometimes the loud insistence of the ego, senses, memories, imagination, fear, anger, and selfish desires can become the sole basis upon which buddhi makes a decision.

When employed regularly, however, the purified buddhi has the reflective quality of a well-polished mirror. It is the instrument through which the conscious mind can know the will of the Divine Reality. With the regular practice of seated meditation, the buddhi increasingly reflects the intuitive library of knowledge of the superconscious mind. The purified buddhi can always discriminate between the preya [worldly, temporary happiness] and the śreya [spiritually beneficial]. When the manas presents us with the choices that echo the calls of the senses, ahaṃkāra (ego), and citta (unconscious mind), the purified buddhi will unerringly define and endorse the śreya – that choice will lead us to our highest and greatest good…”[3]

4. Knower (Parijñātā): The buddhi (intellectual organ) presents the knowledge to the ātmā, which is the true knower. The ātmā is the witness-consciousness (sākṣī) and the substratum of all cognition, while buddhi merely reflects and channels the knowledge gathered.

5. Doer (Karttā): The ātmā, when influenced by the ego (ahaṃkāra), identifies with the body-mind complex and thinks “I am the doer” and desires the fruits of action. While the ātmā itself is nirguṇa (beyond the three guṇas), the ahaṃkāra is saguṇa (composed of the guṇas), and thus the perceived doer (karttā) is classified into three types in the Gītā:

The doer who is free from attachment, free from the speech of egotism, full of steadfastness and enthusiasm, and who is not perturbed by success or failure – he is said to be a Sāttvic doer. — Bhagavad Gītā 18.26

The doer who is swayed by passion, who eagerly seeks the fruit of his karm, who is greedy, violent-natured, impure, and who is moved by joy and sorrow – he is said to be a Rājasic doer. — Bhagavad Gītā 18.27

The doer who is undisciplined, vulgar, obstinate, wicked, deceitful, lazy, despondent, and procrastinating – he is said to be a Tāmasic doer. — Bhagavad Gītā 18.28

Thus, while the ātmā is the ultimate source of consciousness, the guṇa-laden ahaṃkāra attributes agency and thus distorts the doership unless purified by viveka and sādhanā.

6. Organs and Activity (Karaṇa): Once the saṃkalpa (resolve) is made in the buddhi, it initiates action through the manas and the prāṇas, which animate the karmendriyas (organs of action). The action (kṛti) may be physical, verbal, or mental. If the action is purely mental (e.g., contemplation, memory, meditation), then the manas alone acts under the directive of the buddhi. In physical or verbal actions, the respective sensory and motor faculties are employed.

Let me know if you'd like a flowchart or a table summarizing these six stages of Puruṣhakāra Karm or if you'd like to continue with step 7 (Phala – fruits of action).[4]

7. Fruit of Action (Karm) and Its Impressions (Saṃskāra):

Once an action is performed, it creates a dual effect:

External result (karmaphala) – the tangible or intangible outcome experienced as pleasure or pain, success or failure, etc.

Internal imprint (saṃskāra) – the subtle impression stored in the chitta (subconscious mind), which shapes future tendencies, desires, and even rebirth.

The Bhagavad Gītā classifies action (karm) based on the quality of intent, detachment, and wisdom behind it:

That karm which is ordained and is performed without attachment, without desire or hate, with no desire for its fruit, is said to be Sāttvic. — Gītā 18.23

But that karm which is performed by one who wants to satisfy his desires, with great effort and with ego, is declared to be Rājasic. — Gītā 18.24

That karm which is undertaken because of delusion, disregarding the consequences, loss or injury, without regard to one’s ability, is termed as Tāmasic. — Gītā 18.25

Prābhākara Mīmāṃsā Model of KarmSmall text (Six Stages) The Prābhākara school offers a parallel model, deeply analytical, on how puruṣhakāra or human initiative unfolds:

- Kāryatājñāna (Knowledge of Duty):

The initial cognition that “something ought to be done” arises from a sense of duty or recognition of a śāstrīya niyama (scriptural mandate) or an internal moral imperative.

- Kṛtisādhyatājñāna (Knowledge of Doability):

Next arises the realization that the intended act is possible to accomplish through one's effort (kṛti).

- Svaviśeṣattāpratisandhāna (Self-Identification with the Action):

The self then appropriates the action by relating it to one’s own interest or identity, i.e., "I must do this."

- Chikīrṣā (Will to Act):

Then comes the intention or resolve to undertake the act – “I want to do this.”

- Ceṣṭā (Effort):

The volitional effort of the body–mind complex begins – planning, moving, speaking, etc.

- Kriyā (Execution):

Finally, the action is performed externally, completing the chain of volitional activity. [5]

Purification of Buddhi is emphasized by practicing various spiritual disciplines that restrain the manas (mind), chitta (memory-impression storehouse), ahaṃkāra (ego), and the senses (indriya-s). A pure buddhi is essentially of the nature of sattva guṇa—clear, reflective, and luminous—and hence sattva and buddhi are often used interchangeably in the scriptures. When buddhi is tainted by rajas (desire, agitation) or tamas (inertia, ignorance), it becomes clouded, leading to incorrect decisions and binding actions.

But when the buddhi becomes free from these impurities, it no longer generates saṃkalpa (will/desire to act) rooted in ego or attachment. It becomes a transparent instrument through which the Divine Will (Īśvara icchā) can act without obstruction. Such a person, established in śuddha sattva, is referred to as an akartā—a Non-Doer—because their actions are no longer self-driven but flow from higher wisdom, like a flute played by the Bhagavān.

“Purifying the buddhi is essential. The more you cleanse and clarify the buddhi—by the practice of seated meditation and all forms of meditation in action—the greater will be your access to the superconscious mind.” — Adapted from Yogic and Vedāntic teachings[6]

“Yog science recognizes a parallel in human life.The collective noise of the senses (indriya-s), the opinions and projections of the ahaṃkāra (ego), and the persistent power of the chitta’s stored memories and imaginations often become so loud and overpowering that they drown out the quiet, resolute signal of the buddhi (intellect).

To hear that signal—and more importantly, to heed its guidance—the seeker must learn the art of inner silence.

This begins by consciously reducing the volume of the chatter of the manas (restless mind), the cravings of the senses, the distortions of the ego, and the unconscious pull of memory.

This ‘noise reduction’ is accomplished through the practice of attention control, which is the very foundation of Yog. Directing the awareness inward, again and again, is how the luminous voice of the buddhi becomes audible. And once heard, it becomes the inner compass guiding one toward clarity, purpose, and liberation.” [7]

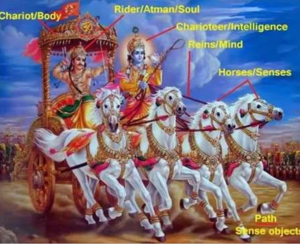

The chariot analogy given in the Kaṭha Upaniṣad 1.3.3–4, as depicted pictorially, is very useful to understand this concept.

A modern scholar uses this analogy from the Upaniṣads to explain:

“This image has many important implications. First, it’s the role of the buddhi to keep you headed in the best direction. The manas serves as reins to steer you for your highest and greatest good. When all the major functions of your mind are coordinated to work in harmony, the real Ātman makes all the decisions. The buddhi, reflecting the will of the Divine Reality, communicates this wisdom to the manas, and the senses and body obey. But when the senses are uncontrolled, they immediately take to the road of desire that promises pleasure. Then we are not determining our destiny. We are enslaved to the whim of our horses.”

“If you are ignoring your Divine Nature at the moment a thought, desire or emotion appears in your awareness, you are likely to disregard or overlook the wise and good counsel of the buddhi and fall sway to the siren call of the senses, ahaṅkāra and citta. You may even be fooled temporarily into believing that you are choosing the preya through your own free will, but actions chosen based on fear, anger and greed will always result in disease.”[8]

References[edit]

- ↑ Perlmutter, Leonard. The Heart and Science of Yoga. AMI Publishers, 2005, New York, pp. 278

- ↑ Perlmutter, Leonard. The Heart and Science of Yoga. AMI Publishers, 2005, New York, pp. 278

- ↑ Perlmutter, Leonard. The Heart and Science of Yoga. AMI Publishers, 2005, New York, pp. 279-280

- ↑ Swami Hariharananda Aranya. Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali with Bhasvati. University of Calcutta, 2000, Calcutta.

- ↑ Anand, Kewal Krishna. Indian Philosophy – The Concept of Karma. Bharatiya Vidya Prakashan, 1982, Delhi.

- ↑ Perlmutter, Leonard. The Heart and Science of Yoga. AMI Publishers, 2005, New York, pp. 279-280

- ↑ Perlmutter, Leonard. The Heart and Science of Yog. AMI Publishers, 2005, New York, pp. 281

- ↑ Perlmutter, Leonard. The Heart and Science of Yoga. AMI Publishers, 2005, New York, pp. 283-284