Talk:Vātsalya Bhāva: Bhagavān as a Loved Child

By Vishal Agarwal

‘Vatsa’ means a ‘calf’. A mother cow is known for its love for her baby calf. In Vātsalya Bhakti, the Bhakta is a parent of his Ishtadevatā, treating Him/Her like a little child lovingly, protectively, and indulgingly. The Bhagavan can be either a Divine Son or a Daughter. The imagery of the Deity being likened to a baby or a child is found in the Vedas too. For example-

Our thoughts caress Indra, the Devta of Strength…just as the cows lick their calf. Rigveda 3.41.5

Worship of the One Supreme Being through icons, sacred symbols, and elaborate ceremonies and prayers was aligned among six traditions of worship – Shākta, Vaishṇava, Shaiva, Gāṇapatya, Kaumāra and Saura. In many of these traditions, which comprise practically all Hindus today, Bhagavān is often worshipped as a child, or children are revered as embodiments of Divinity.

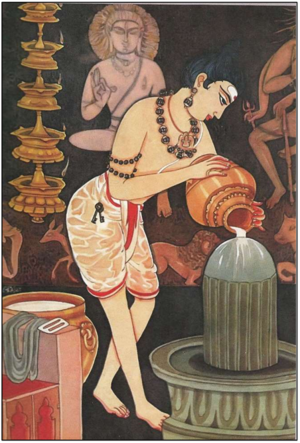

In the Shaivite Hindu traditions, a very beautiful story is narrated from the life of Nayanmar

Tiruneelanakkar and his wife on the vātsalya bhāva of Bhakti. Once, the couple went to a Shiva Mandir to perform worship, when they saw a spider fall on the Shivalinga. Immediately, the lady blew on it and the spider fell and scampered away.

But her husband was furious and said to his wife, “Don’t you know that blowing at a Mūrti with your out-breath is a sin? I am very annoyed with you. From now onwards, you will no longer be my wife.” He abandoned his wife at the Mandir itself, and went home! That night, Tiruneelanakkar had a dream in which he saw that the Shivalinga was covered with boils all over wherever the spider had sprayed its poison. But, there was one spot that was free of boils- the spot where his wife had blown her breath to remove the spider. In the dream, Shiva said, “Your wife blew away the spider out of the love that a mother has for his child. Like a mother, she ensured that the spider would not bite me and blew it away. It was due to her love, that the spot where her breath hit my Shivalinga had no boils. Therefore, you should return to the Mandir, and bring your wife back. I am not upset with her. I deeply appreciate the maternal love that she has for me.”

Tiruneelanakkar woke up and rushed to the Mandir. He apologized to his wife and brought her back with honor[1].

It might be pointed out however that in Shaivite Hindu Dharm, Bhagavān Shiva is not worshipped as a child and he never takes an Avatāra with human parents.

Shākta (Worshipping the Divine Mother):

The Devi has eight major forms according to tradition, and numerous rituals directed towards her involve worship (called ‘kanjaka-puja’) of pre-pubescent girls as manifestations of her eight forms. Pilgrimages to several Devi shrines (such as Vaishno Devi in Jammu, India) are concluded with this ritual. In Nepal, a girl is periodically selected from a particular lineage and worshipped as a living goddess till she reaches puberty. In an annual ritual, she is taken out in a ceremonial procession in a chariot, and even the King of Nepal participates in pulling her chariot[2]. These examples show how in this Hindu tradition, the Devī is worshipped also as a loved daughter.

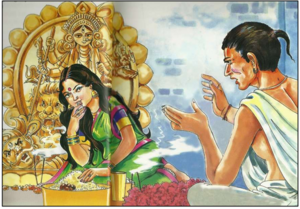

Story: The Devi Comes As Sarvamangalā

Once, a poor Brahmana and his wife in a village in Bengal had a beautiful daughter named Sarvamangala. She was their only child. One day, a wealthy merchant from another village saw her and fell in love with her beauty. He approached her father and asked for permission to marry her. The Brahmana thought that Sarvamangala being their only child, would be lonely after she married and left them. But as her father, it was his duty to marry her to a good groom. Therefore, with a heavy heart, he married Sarvamangala to the merchant, after getting a promise that he would allow her parents to come and visit her as often as they wished, and would allow her to visit her parents frequently.

During the Navaratri festival, Bengali Hindus install a clay Mūrti of Ma Durga and worship her for nine days and nights. The entire period is marked by joyous celebrations, prayers, dancing, and eating delicacies. The Brahmana felt very lonely this year because his beloved daughter was no longer with them to prepare for the festivities. The lonely father therefore went to the merchant and begged him to allow his daughter to come to their home for the festival. But the merchant refused, saying, “We are expecting guests in our own home. How can we send your daughter with you?”

With a heavy heart, the Brahmana started walking back to his village. But he had taken just a few steps when his daughter called him from behind, “Father, my husband agreed to let me come with you this year. His mother will take care of the guests.”

Sarvamangala’s father was overjoyed to see his daughter come with him. The festival was, as every year, a joyous event, and Sarvamangala did all the preparations as usual. On the last day, as the festival drew to a close, Sarvamangala suddenly disappeared!

The Brahmana and his wife thought that perhaps her husband had come to take her back with him. To thank their son-in-law, the Brahmana went a few days later to his daughter’s village. When he met his daughter, he said, “I am so glad that you could come with us this year to celebrate the festival. We will always remember the wonderful time that we had with you.” But Sarvamangala gave a puzzled look and said, “But Dad, I never left my home. Don’t you remember that my inlaws wanted me here to help out with serving our guests?” The Brahmana was surprised to hear his daughter’s reply. He realized that it was none other than Devi Durga, who had taken the form of their daughter to help them out and make their festival a joyous occasion.

The Brahmana returned to his home and the couple worshipped Ma Durga saying, “Thank you for answering our prayers. You knew that we’d be lonely during the festival due to the absence of Sarvamangala. And therefore you took her form and came to spend the nine days with her. You are loving and compassionate towards your devotees!”

In the Vaishnava Hindu traditions, Vishnu is worshipped generally through his two major incarnations (‘avataras’) namely Rama and Krishna. Hindu texts contain dozens of sacred stories narrating the childhood and teenage exploits of the two, especially the latter. The doctrine of vātsalya bhakti with its strong Vaishnava associations advocates loving God as a mother loves her child. Between 500-1000 CE, Alvar saints composed numerous devotional songs in the Tamil language to celebrate the themes of the divine childhood. This trend picked up all over the Indian subcontinent, and numerous saint poets (e.g., Sūrdās in Hindi) wrote thousands of devotional poems describing the wonderful pranks (‘līlā’) of child and teenage Krishna. In his poems, the description of Shri Krishna’s childhood activities is not merely an ‘ornamentation’, but rather forms the core theme. Iconic representations of Krishna as a child (‘the butter thief’) are very common and elders often narrate stories of his pranks to children.

Children are themselves often referred to as child Krishna or child Rama in homes, and the ‘birthdays’ (the days on which Bhagavan Vishnu incarnated in these forms) are celebrated as major festivals. Nativity scenes of Krishna and Rama are depicted in households and temples. Icons depicting them as children are placed on a swing and lullabies are sung to them. These rituals naturally endear a lot to children. Temples at their respective sites of birthplace in Mathura and Ayodhya were later displaced forcibly with mosques but are nevertheless visited by millions of Hindu worshippers even today.

The Bhakti poetry of Sant Sūrdās is the most famous example of this Bhāva. But even a thousand years earlier, Periazhvar wrote very moving verses describing baby Krishna, some of which we reproduce below from the Maṇipravalā (Tamil mixed with Sanskrit) compositions included in the compilation called Divyaprabandhaṃ-

He rolls in the dust so that the jewel on his forehead keeps swinging and the bells on his waist tinkle. Big Moon, look at the play of my son Govinda if you have eyes on your face, and then be gone! My little one, precious to me as nectar, a blessing in my life, is calling you, pointing repeatedly with his little hands. But Moon, if you wish to play with this little cute dark boy, then do not hide behind the clouds. Keep being visible and come near. Do not disregard him just because he is a baby. Did he not sleep on a banyan leaf? If he becomes annoyed with you, he will leap up and catch a hold of you. Big Moon, do not disregard my Bhagavan but come close to him joyously. Thirumozhi 1.5

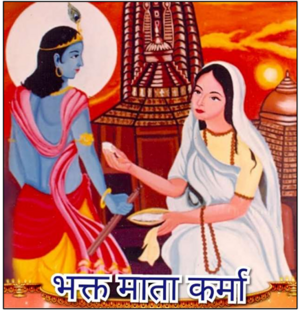

Story:The Khichuri of Karamā Bāī

It is a tradition to offer Khichuri to Bhagavān Jagannātha’s image at Puri before He is offered anything else to eat. The Khichuri is referred to as ‘Karamā Bāī’s Khichuri’. A very charming story is narrated about the name in the Bhaktamāla. Karamā Bāī was a poor Jat widow who lived alone in a village named Kalwa close to Nagaur, in eastern Rajasthan. She had an image of Bhagavan Jagannatha, whom she adored lovingly as her child. Every morning, she would offer the image of some Khichuri that she had cooked freshly, as if she were feeding her child. Being poor, that is all she could offer to the Bhagavān. Many a time, in her eagerness to feed the Bhagavān’s image, she would not even clean her hut or take a bath before cooking and offering the Khichuri. This was opposed to the Hindu traditions that say that one must be pure and clean and follow specific rituals while offering food to images of theBhagavān.

Once, she went to the town of Puri to witness the Jagannatha Rath Yatra. She was so charmed by the temple festival that she decided to spend a few days in the town. The image of Jagannatha at the Mandir reminded her of the image that she had worshipped back in Kalwa. So the next morning, she prepared Khichuri as usual before cleaning the kitchen and taking a bath. A learned scholar happened to stop by and when he saw Karamā Bāī serve the Khichuri to the Bhagavān, he scolded her, “How can you serve Bhagavān without first cleaning the kitchen and taking a bath? This is against the scriptures. It is an evil thing to do. I will teach the proper procedure that you must follow, and the verses that you must recite to offer food to the Bhagavān in the proper way.” Karamā Bāī, being simple-hearted that she was, took the scholar’s advice to her heart. The scholar instructed her on the correct procedure and the prayers to be chanted and went his way. Karamā Bāī then cleaned the kitchen and went to take her bath thinking that she would make Khichuri afresh and offer it ritually to the Bhagavān as she had been taught.

The result was that she became very late in cooking the Khichuri. After she had hurriedly served it to the image that she had brought with her, she rested with content that she had offered it per the instructions of the religious scriptures.

Meanwhile, when the Pujari of the Jagannath Temple opened the doors to offer the sumptuous morning feast to Bhagavān, he was shocked to note that some Khichuri was smeared on the face of the Bhagavān. He promptly shut the doors again and asked the visiting Bhaktas to wait for some time. He prayed, “Bhagavān, whose Khichuri have you eaten today? Was there some flaw in our feast that you chose to eat the Khichuri cooked by someone else?” Miraculously, the image spoke, “Every day early in the morning, I have relished Karamā Bāī’s Khichuri. She would hurry in the morning and cook it for me without even waiting to clean her kitchen and take a bath so that she would not keep me waiting. She has served me lovingly as a mother who feeds her hungry child. Today, she got late following some rituals that a learned Pandit taught her. As a result, I barely had time to eat a few morsels before I rushed to the Mandir to eat this feast that is offered to me every morning because I did not want to disappoint my long-time devotees. The truth is that rituals are important, but only till Bhakti has not sprouted in one’s heart. Once the heart of my Bhakta becomes full of love, rituals become irrelevant. Karamā Bāī loves me as a mother loves her child. Therefore, I like her Khichuri a lot and prefer to eat that as my first meal in the day.”

The Pujari was overjoyed that a pure and true Bhakta lived right within the town of Puri. He informed the King. Thereafter, as long as Karamā Bāī was alive, a pot of Khichuri was served to the Bhagavān every morning. And after she passed away, her recipe has been used to serve the Khichuri to the Bhagavān every morning down to the present times, and is still referred to as ‘Karamā Bāī’s Khichuri’.

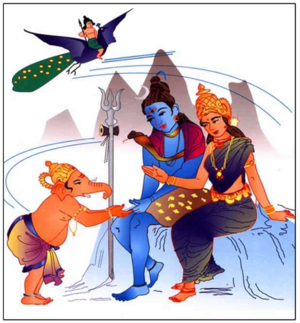

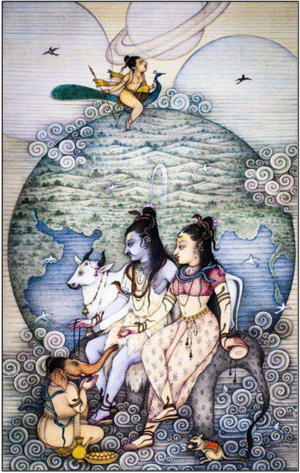

Ganapatya (Worship of Ganesha/Ganapati, the son of Parvati and Shiva): The very form of Ganapati as an elephant-headed deity appeals to children, who often have a personal icon of the deity in their homes. He is primarily worshipped as an adorable child, and tales of his childhood are often used as parables to inculcate virtues such as respect for elders among children. Most of the sacred stories in Hindu scriptures concerning him relate to his childhood and youth.

Ganesha and Karttikeya – Who won the race?

One day, Bhagavān Shiva and Devi Parvati called their two sons Ganesha and Karttikeya. Parvati said to them – “I want you two to race. Both of you should start from here. Then go around the world one time and return here. I have a very tasty mango. Whichever one of you comes first, will get to eat this mango.

Now Karttikeya was very happy when he heard this. He was sure that he would win the race because he could fly on a peacock. But Ganesha only had a mouse on which he could travel. So how could Ganesha beat him in the race? As soon as their father Shiva said ‘one, two, and three…..” Karttikeya sat on his peacock and started flying on his peacock to go around the world. But Ganesha did not even start! Instead, he folded his hands in a ‘Namaste’ and bowed in front of his parents. Then, he just took a round of his parents and said – “Dear Mom and Dad, you are more important to me than the whole world. Therefore, I will just go around you three times.” Just after Ganesha had completed his third round, Karttikeya landed back on his peacock.

Karttikeya was so happy to see that Ganesha had not even left that place. “Aha,” he said, “I have won the race.” “No,’ said their mother Parvati, “It is your brother Ganesha who won.” Karttikeya was shocked. “This is cheating, Ganesha did not even leave this place,” he said.

But their parents explained to him – “Look, we only wanted to test you two brothers. Ganesha won because he showed that he loved his parents more than the whole world. But you thought you could leave your parents behind and win a prize. So, the mango will be given as a prize to Ganesha.”

Karttikeya learned a very nice lesson from his brother Ganesha. He learned that no one else in the world cares for us as much as our parents. Therefore, we should always give more importance and respect to our parents than anyone else in the whole world. This is what Ganesha did, and therefore he won the race!

Other Traditions: Other Hindu religious traditions that cannot be compartmentalized within the above six modes also have their versions of young deities or Gurus. For instance Ayyappan[3], whose temple atop the Sabarimala hill in the Indian state of Kerala draws millions of worshippers each year, is said to be a divine teenager who combined the powers of Shiva and Vishnu.

References[edit]

- ↑ Nandakumar, Prema. Saints of Saivism. Sri Ramakrishna Math, 2013, pp. 115-116.

- ↑ Regmi, Jagadish C. The Kumari of Kathmandu. Heritage Research, 1991.

- ↑ "Quasi-official website of the temple." Sabarimala, <http://www.ayyappa.com/Sabarimala.htm>.