Talk:What shapes our Personality:Effects of Previous Lives

By Vishal Agarwal

Whereas modern theories of personality acknowledge the first three factors,

- Genetics

- Environment

- Personal efforts, but they do not include the last factor now being discussed, which is

- the effect of our previous lives on our personality.

Although modern psychology indicates that the child develops his personality only by the age of four, it is seen that each child appears to be born with an inherent nature even before he turns four years of age- “And yet, why does it appear that children often emerge from the womb with very different and distinct characteristics – characteristics that emerge long before the child is old enough to experience anything that could emerge long before the child is old enough to experience anything that could conceivably shape his or her personality? Additionally, many child psychologists claim that a child’s basic personality is often set by the age of four, but, if so, how exactly are later experiences molding the future personality? If a child is naturally impatient, for instance, being put into a situation in which patience is called for will more likely be perceived as torturous rather than a growth experience. The child may learn to deal with his impatience in more constructive ways as he or she grows older, but the underlying impatience will still be there – it’s simply under better control. If experiences shape our personality, however, then being forced to wait should eventually result in a more patient persona, yet this is seldom the case. Life experiences may shape our coping mechanisms or even reveal to us things we may need to work on, but they rarely alter a person’s basic nature…”[1]

Modern psychological theories are simply inadequate in explaining why siblings too exhibit great differences in their personalities even during their infancy- “Despite what Western psychology teaches us about the overriding importance of family influence, those of us who have observed young children are immediately struck by the great differences between one child and another within the same family. Psychologists try to account for this through differences in body, brain, or genetic inheritance and then also suggest that the family environment is never quite the same for any two children. However, those who are around children find that the differences between siblings are often so great that the aforementioned factors, important as they may be, never seem to quite account for the observable facts. Even an infant who has not yet been subjected to much family influence may already show striking differences from the way its brothers and sisters behaved at the same stage of development. The notion that the child may bring its innate tendencies into its present birth seems to fit the facts more closely, although it certainly runs into the prejudices of most Westerners and is quickly rejected on that account.”[2]

Śāstras gives the obvious explanation for this – that one’s personality is shaped by actions performed repeatedly in earlier lives- The physical, mental, and verbal abilities of people become apparent in this life due to practice in previous lives, despite being reborn. Vāmana Purāṇa 64.18 The Yogshāstra discusses quite elaborately how the saṃskāras, or the effects of voluntary actions, influence the very species or state (e.g. rich or poor) into which we are reborn. A portion of these saṃskāras also shape our personality in our current life – our likes and dislikes, aptitudes, phobias, philias, innate skills, natural talents, and so on. As Swami Vivekananda explains- “Just as a large number of small waves create a big wave, the effects of Karm accumulate to form tendencies, an aggregation of which in a personality we call character. Man is like a center attracting all the powers of the universe towards himself, fusing them all and sending out his inner reaction to them as a current – the manifestation of his will, which in common parlance we call his personality or character.”[3]

The story of the rebirths of King Bharata in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, as retold by Swami Vivekananda, brings together numerous concepts in this section and several preceding ones:

Story: The Many Lives of Emperor Bharata

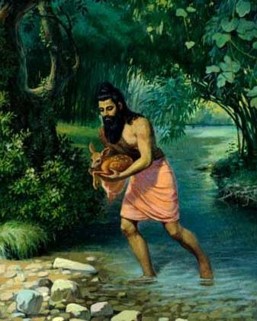

“The great king Bharata in his old age, gave over his throne to his son and retired into the forest. He who had been ruler over millions and millions of subjects, who had lived in marble palaces, inlaid with gold and silver, who had drunk out of jeweled cups – this king built a little cottage with his own hands, made of reeds and grass, on the banks of a river in the Himalayan forests. Then he lived on roots and wild herbs, collected by his own hands, and constantly meditated upon Him who is always present in the soul of man. Days, months, and years passed. One day, a deer came to drink water nearby where the royal sage was meditating. At the same moment, a lion roared at a little distance off. The deer was so terrified that she, without satisfying her thirst, made a big jump to cross the river. The deer was with young, and this extreme exertion and sudden fright made her give birth to a little fawn, and immediately after, she fell dead. The fawn fell into the water and was being carried rapidly away by the foaming stream when it caught the eyes of the king. The king rose from his position of meditation and rescued the fawn from the water, took it to his cottage, made a fire, and with care and attention, fondled the little thing back to life. Then the kindly sage took the fawn under his protection, bringing it up on soft grass and fruits. The fawn thrived under the paternal care of the retired monarch and grew into a beautiful deer. Then, he whose mind had been strong enough to break away from lifelong attachment to power, position, and family, became attached to the deer which he had saved from the stream. As he became fonder and fonder of the deer, the less and less he could concentrate his mind upon the Īshvara. When the deer went out to graze in the forest, if it were late in returning, the mind of the royal sage would become anxious and worried. He would think, “Perhaps my little one has been attacked by some tiger – or perhaps some other danger has befallen it; otherwise, why is it late?”

Some years passed in this way, but one day death came, and the King lay himself to die.

But his mind, instead of being intent upon the self, was thinking about the deer; and with his eyes fixed upon the sad looks of his beloved deer, his soul left the body. As a result, he was born as a deer in the next birth. But no Karm is lost, and all his great and good deeds as a king and sage bore their fruit. The fruit was a born Jatismara, and remembered his past birth, though he was bereft of speech and living in an animal body. He always left his companions and was instinctively drawn to graze near hermitages where oblations were offered and the Upanishads were preached.

After the usual years of a deer’s life had been spent, it died and was born as the youngest son of a rich Brahmin. In that life also, he remembered all his past, and even in his childhood was determined no more to get entangled in the good and evil of life. The child, as it grew up, was strong and healthy, but would not speak a word, and lived as one inert and insane, for fear of getting mixed up with worldly affairs. His thoughts were always on the Infinite, and he lived only to wear out his past Prarabdha Karm. Over time, the father died, and the sons divided the property among themselves; and thinking that the youngest was a dumb, good-for-nothing man, they seized their share. Their charity, however, extended only so far as to give him enough food to live on. The lives of the brothers were often very harsh to him, putting him to do all the hard work; and if he was unable to do everything they wanted, they would treat him very unkindly. But he showed neither vexation nor fear, and neither did he speak a word. When they persecuted him very much, he would stroll out of the house and sit under a tree, by the hour, until their wrath was appeased, and then he would quietly go home again.

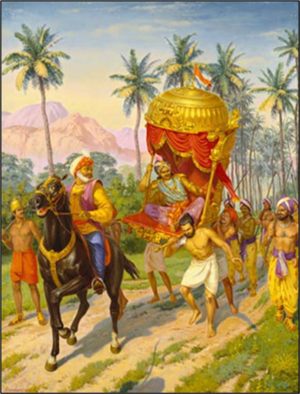

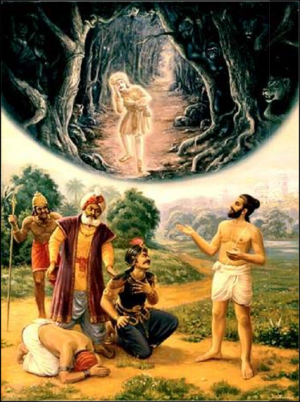

One day, when the wives of the brothers had treated him with more than usual unkindness, Bharata went out of a tree and rested. Now it happened that the king of the country was passing by, carried in a palanquin on the shoulders of bearers. One of the bearers had unexpectedly fallen ill, and so his attendants were looking about for a man to replace him. They came upon Bharata seated under a tree; and seeing that he was a strong young man, they asked him if he would take the place of the sick man in bearing the king’s palanquin. But Bharata did not reply. Seeing that he was so able-bodied, the king’s servants caught hold of him and placed the pole on his shoulders. Without speaking a word, Bharata went on. Very soon after this, the king remarked that the palanquin. But Bharata did not reply. Seeing that he was so able-bodied, the king’s servants caught hold of him and placed the pole on his shoulders. Without speaking a word, Bharata went on. Very soon after this, the king remarked that the palanquin was not being evenly carried, and looking at the palanquin, addressed the new bearer, saying, “Fool, rest a while; if thy shoulders pain thee, rest a while.” Then Bharata, laying the pole of the palanquin down, opened his lips for the first time in his life, and spoke, “Whom do you, O King, call a fool? Whom do you ask to lay down the palanquin? Who do you say is weary? Whom do you address as ‘you’? If you mean, O King, by the word ‘you’ this mass of flesh, it is composed of the same culture as yours; it is unconscious, and it knows no weariness and it knows no pain. If it is the mind, the mind is the same as yours; it is universal. But if the word ‘you’ is applied to something beyond that, then it is the Self, the Reality in me, which is the same as in you, and it is the One in the universe. Do you mean, O King, that the Self can ever be weary, that it can ever be tired, that it can ever be hurt? I did not want, O King – this body did not want to trample the poor worms crawling on the road, and therefore, in trying to avoid them, the palanquin moved unevenly. But the Self was never tired; It was never weak; It never bore the pole of the palanquin: for it is omnipotent and omnipresent.” And so he dwelt eloquently on the nature of the soul, and the highest knowledge, etc.

The King, who was proud of his learning, knowledge, etc., and philosophy, alighted from the palanquin, and fell at the feet of Bharata, saying, “I ask thy pardon, O mighty one, I did not know that you were a sage when I asked you to carry me.” Bharata blessed him and departed. He then resumed the even tenor of his previous life. When Bharata left the body, he was freed forever from the bondage of birth.”[4]

References[edit]

- ↑ Danelek, J. Allan. Mystery of Reincarnation. Llewellyn Publications, 2005, Woodbury, Minnesota (USA). p. 45.

- ↑ Swami Rama and Swami Ajaya. Creative Use of Emotion. Himalayan Institute India, 1986, Allahabad. p. 92.

- ↑ Swami Tapasyananda. The Four Yogs of Swami Vivekananda. Advaita Ashram, 2010, Kolkata. p. 1-2

- ↑ Vivekananda, Swami. Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. Vol. 4, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, Calcutta, pp. 111-114.