Akka Mahādevi

By Swami Harshananda

The middle ages (A. D. 900-1600) were a ‘golden era’ for religious revival. Most of the Bhakti Movements belong to this period. The movements in the North were predominantly Vaiṣṇavite in character. The movements in the South were both Śaivite and Vaiṣṇavite, the former being the more widespread. The movement of the Śivaśaraṇas of Karnataka with its philosophy and religion of Vīraśaivism, became and still is a force to reckon with. The stress on bhakti (devotion) as an easy mode of sādhanā (spiritual practice) available to everyone and the loosening of the caste restrictions among the bhaktas (devotees of God) thereby giving the masses a chance to mix on equal terms with the classes, were the special features of this movement.

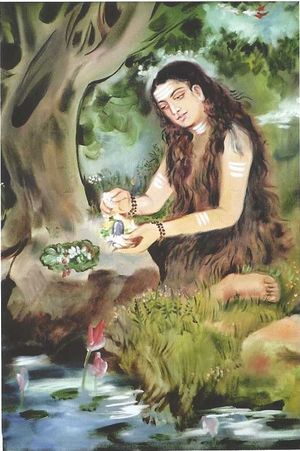

Among the sixty well-known mystics of the Vīraśaiva movement most of whom were men, Akka Mahādevi (also known as Mahadeviyakka) has occupied an important place. Born probably in 1130 A.D. at Uḍutaḍi (a village in the Shivamogga District of Karnataka) as the only child of a devout Śaiva couple, she had instinctively cultivated madhurabhakti, loving God Cannamallikārjuna (an aspect of Śiva) as her spouse.

In her youth, Kauśika, the king of the place sought her hand in marriage. She married him after laying down certain conditions. When these conditions were broken by him she renounced the world and went away as a wandering minstrel. At Kalyāṇa in northern Karnataka she joined the group of devotees of the anubhava-maṇṭapa (a forum for discussion and exchange of views on spiritual life and experience) led by Basaveśvara and Allama Prabhu. After being initiated by Basaveśvara and feeling spiritual elevation, she retired to Srīśaila (now in Andhra Pradesh) where she was ‘united with her Lord Śiva,’ probably in 1166 A.D.

Unlike the vacanas, a kind of lyrical prose of Basaveśvara and others, her vacanas describe her longing for union with her divine spouse and the joy of fulfillment. A few of them also deal with the practical aspects of spiritual life.

References[edit]

- The Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Swami Harshananda, Ram Krishna Math, Bangalore