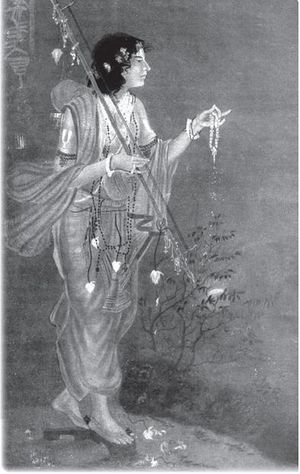

Narada

By Swami Purnananda

What would you feel if you were asked the question: How did you die? You would perhaps be bemused for a while and then feel convinced that your interlocutor was out of his head. But when Narada was asked this question by Krishna Dvaipayana Vyasa he was not taken by surprise; nor did he feel uncomfortable. Instead, his face lit up with a radiant smile as he proceeded to answer this seemingly unanswerable question.

Counselor to Vyasa[edit]

Once Vyasa was lamenting over the great dissatisfaction and unrest that was tormenting his mind even though he was well versed in the Vedas, had lived in consonance with dharma, and devoted himself to the welfare of all beings. He sat on the banks of the river Saraswati, cogitating on the cause of the depressive thoughts that were constantly weighing on his mind. Just then, Narada happened to arrive at Vyasa’s ashrama in the course of his perpetual peregrination across the three worlds. Though he was received with due respect, Narada realized that Vyasa was disturbed. So after praising him for his many achievements, he enquired afer his well-being:

Jijñāsitamadhītam ca yat-tat-brahma sanātanam; Athāpi śocasyātmānam-akrtārtha iva prabho.

O master of oneself, you have realized the eternal Brahman by the process of proper discrimination; why then do you look mentally troubled, as though possessed by a sense of futility.[1]

Vyasa replied: ‘I am aware that I have the excellences you mention; yet I have no peace of mind. I feel dissatisfied. I think I have some shortcoming, which I am unable to make out. You are a man of wisdom, the son of the Creator, and a beloved devotee of the Lord. You travel all over the three worlds and can penetrate into everything. You know the thoughts of every being. Be kind, I pray, and tell me the causes of my dysphoria.’

Narada pointed out the reason for Vyasa’s distress in a succinct reply: ‘You have not adequately described the unblemished glory of the Supreme Lord in your works. That is why he is not pleased with you. And for that reason, I reckon, your knowledge is incomplete.’ After elaborating upon his statement, he advised Vyasa to recall the divine play of the Lord by means of samadhi (and describe it) for liberation from all worldly bonds: urukramasyākhila-bandhamuktaye samādhinānusmara tad-vicestitam.

By the Lord's direction, living entities accept, with a material body, to be bound to birth and death, sadness, illusion, fear, happiness and distress; and act according to their karma [2]

The Housemaid’s Son[edit]

While dwelling on the need for contemplating and expounding the glories of Bhagavan, Narada recalled one of his previous births as a housemaid’s son: ‘In one of my previous lives, I was born to a housemaid who was engaged in a household of Vedic ritualists. I was appointed to serve the yogis who gathered at the place for cāturmāsya, retreat during the rainy season. Although impartial by nature, they were very gracious to me as I had engaged myself sincerely in their service. Moreover, I was self-restrained and devoid of childish frivolity. I was also obedient, reserved, and not fond of sports or games like other children. Having obtained their consent, I once partook a little of the remains of their meal. That was enough to free me from all past sin. With my mind thus purified, I felt greatly inclined to listen to the divine glories of the Lord that the sages were always engaged in singing. Gradually I developed an irresistible attraction for the Divine. My mind became steady in its devotion to the Lord and I could realize that my gross and subtle bodies, born of ignorance, were super-impositions on my real Self, the Atman. Thus, by hearing continuously the glories of the Lord from these great souls, throughout the rainy season and autumn, there arose in my heart that devotion which destroys rajas and tamas. As they were leaving, the kind and compassionate sages instructed me in the transcendental spiritual truths that are revealed by the Lord himself, for though a mere child, I was devoted, humble, guileless, respectful, restrained, and obedient by nature. By means of this knowledge, I could realize the infuence of maya, the power of the Lord; and this knowledge leads one to divine beatitude. So I also attained this state and became one of the pārsadas, immediate associates, of the Lord.’

Vyasa’s curiosity was aroused by this remarkable story. He wanted to know more about the housemaid’s son, and his questions included the following: ‘Katham cedam-udasrāksīh kāle prāpte kalevaram; in the end, how did you give up that mortal frame of yours?’ (1.6.3). Narada replied: ‘I was the only son of my mother. Though she was deeply attached to me, being but a mere housemaid, she was hardly capable of properly looking after me. All beings are under the control of Providence, much like puppets in the hands of a puppeteer. I was still a mere boy when my poor mother was fatally bitten by a venomous snake while on her way to milk a cow. Taking this to be a blessing (in disguise) for my welfare, I left home and started walking north, surrendering myself to the divine will. Passing through towns, villages, farms, and mines; through groves, jungles, and forests; and by the side of lakes flled with lotuses, at last I reached a dense and forbidding forest. Hungry, thirsty, and tired, I refreshed myself by bathing and drinking at a forest stream. Sitting under a pipal tree in that remote and desolate forest, I started meditating upon the Supreme Being immanent in oneself, as instructed by the sages. As I meditated on the lotus feet of the Lord, with a mind filled with devotion, and eyes brimming with tears due to the intensity of aspiration, my beloved Lord appeared in my heart. O Vyasa! How can I express the joy I experienced! With my hair standing on end in ecstasy, I was lost in an ocean of divine bliss. But alas! The vision disappeared and I could no more see that pleasing divine form that destroys all sorrow. I was utterly upset; I got up from the seat with a distressed mind. I tried again to dive deep into my mind and search for the divine form, but all effort proved futile. Deprived of the vision of the Lord, I became filled with frustration and anguish.

‘Just then, as if to assuage my grief, the Lord spoke to me in a deep, sweet voice: “My boy! Lament not, you shall not have any further vision of me. To those who are not established in yoga, whose minds are smeared with the taint of worldliness, I remain invisible. O taintless one! You have had my rare vision once, and this I bestowed to enhance your yearning for me. With the increase in right yearning, my devotees gradually give up all desires lodged in their minds and become pure; and only those that are pure in heart can have my constant vision. Through service to pure souls—even though it was only for a short while—you have developed unflinching devotion towards me. You will give up this mortal frame of yours within a short time and have the rare privilege of being one of my pārsadas. Moreover, your devotion to me will never be diminished and your recollection of me will not be affected by Creation or Dissolution.”

‘That formless Elysian voice which had assumed a spatial form, as it were, in my heart ceased to be heard thereafer. I bowed my head in salutation to that Noble Being. Repeating the auspicious names of the Lord, the Infnite Being, and recollecting his sacred and mysterious acts, I became contented in mind—devoid of attachment and shame, and free from egotism and malice. Waiting eagerly for the time wen I would be directly associated with the Lord, I kept wandering across the globe. For me, who was intensely devoted to the Lord, pure in heart, and totally detached from all mundane objects, the moment of departure arrived suddenly like a flash of lightning. The sacred and pure godly body, bhāgavatī tanu, made of pure sattva and fit for the service of the Lord, was generated in me even as my mortal body born of the five elements dropped away on exhaustion of its past karma.

‘At the end of the cosmic cycle, when all creation was withdrawn into the causal state and the Supreme Being lay resting on the causal waters, kārana salila, I too entered his divine body along with Brahma, his creative breath. After a thousand divine eons, when the Lord again resolved to create this world, I was born of his vital breath along with such rishis as Marichi and Atri. Committed to celibacy, I have been roaming the three worlds unhindered, by the grace of the Lord, chanting the divine name “Hari”, striking melodious notes on the strings of the veena that the Lord has himself given me. When I sing his glories to the accompaniment of the celestial lute, the Supreme Lord of endearing fame and sanctifying feet appears in my heart, as if promptly responding to a call by one’s name. This is the story of my death and birth, which you wanted to know.’[3]

We learn from this story that Narada had descended directly from Brahma, the Creator. At the beginning of every cosmic cycle, Narada accepts a gross body, and at the time of cosmic dissolution he merges into the Lord. He never loses the memory of his birth and disappearance in each cycle. Sri Ramakrishna pointed out that Narada is a nitya jiva, an ever free, eternally perfect being. Being a direct associate of the Lord, he is a free soul, never caught in the clutches of maya. Having broken the fetters of karma, he has gone beyond the bondage of birth and death as well as the other miseries of the world.

Seeker of Self-knowledge[edit]

The cosmic dimensions of Narada’s life make it very difcult for us to reconstruct his life history. He was, of course, a very famous sage even at the time the Aitareya Brahmana was recorded. He is widely recognized as a fascinating, albeit difficult to understand, personality. Narada is also a man of wisdom. Yet in the Chhandogya Upanishad, we find him approaching the sage Sanatkumara for spiritual instruction. Sanatkumara, one among the first four sannyasins, was a sibling to Narada, having been born of Brahma. When Narada requested Sanatkumara to teach him, Sanatkumara said: ‘Tell me what you already know, and I shall teach you what is beyond that.’ Narada replied with a long list: ‘I have studied the Rig Veda, Yajur Veda, Sama Veda, and Atharva Veda the fourth; Itihasas and Puranas—history and mythology—which are the fifth Veda; Vyakarana, by means of which the meaning of the Vedas is understood; the rites for manes, mathematics, natural science, mineralogy, logic, ethics, etymology, science of rituals, material sciences, the science of warfare, astrology, herpetology, and the fine arts—I know all this. But, O venerable sir, even after this vast study I am only a mantravit, knower of texts, not an ātmavit, knower of the Atman. I have learnt from persons of wisdom like you that the knower of the Atman alone can cross the ocean of misery; and I am afflicted with misery. Therefore, my Lord, rescue me from this ocean of misery.’ [4]

Sanatkumara did impart the knowledge of Brahman to Narada. But what interests us here is the wide range of Narada’s study and the vast repertoire of skills he commanded. The irony is that despite possessing such vast knowledge—virtually impossible for any one human being to attain in a lifetime—Narada lacked peace of mind. That is why he came to Sanatkumara seeking the knowledge of the Self, for only this knowledge can give one peace of mind. Self-knowledge or the knowledge of Brahman is called parāvidyā, supreme knowledge, and all else is inferior knowledge, aparāvidyā. As Sri Ramakrishna has said, ‘That alone is Knowledge through which one is able to know God. All else is futile.’[5]

Secular knowledge has its own value. Hence the Chhandogya Upanishad speaks of two types of knowledge, dve vidye, the parā and the aparā. But Narada’s experience reminds us that peace of mind or genuine contentment and happiness cannot be had without the knowledge of God. Narada had realized this truth; therefore he could tell Vyasa to describe the divine play and glory of the Lord, listening to which would arouse unflinching devotion to God in human hearts. And such devotion brings lasting peace and bliss.

An Enigma[edit]

His wisdom notwithstanding, there are times when Narada behaves like any common person, at times even like an ignorant one. This lends his character its intriguing aura. Here is one such instance: Once Narada became a little proud of his musical abilities—that none could play the veena as well as he did. Bhagavan Vishnu came to know this and thought: ‘My devotees should not be boastful. So Narada ought to be taught a lesson.’ He took Narada for a walk into a forest. Suddenly they heard someone weeping. On following the sound, they found some women with badly deformed bodies crying in pain. Vishnu asked them who they were and why they were weeping. The women replied: ‘We are the Raginis, the deities of music. Our bodies have been disfigured by Narada’s erroneous selection of notes. He is tone-deaf and has little musical sense. His singing is out of tune with his music, and this has disfigured us.’ Narada was humbled.

On the face of it, many of Narada’s actions and endeavors appear strange and meaningless; but deep meaning underlies each of them. He is intelligent and wise, a good counselor and a great devotee of the Lord. He wishes all beings well. He has no enemies. He can visit anybody, anywhere and at any time, irrespective of their social standing whether they be gods, demons, or human beings—for he is a sincere counselor. All the same, his intrusions do look awkward at times.

On hearing a celestial voice warning him that he would meet his death at the hands of the eighth issue of his cousin Devaki, Kamsa, the wicked ruler of Mathura, decided to kill Devaki. Devaki’s husband Vasudeva managed to save her life by promising to hand over all their children to Kamsa. When their first son Kirtiman was born, Vasudeva took the

baby to Kamsa with a heavy heart in order to keep his promise. Kamsa was pleased by Vasudeva’s strict adherence to truth and his even-mindedness towards friend and foe. He said to Vasudeva: ‘O Vasudeva, take this child back with you, I have no cause to fear him; it is only by your eighth child that I am destined to die.’ No sooner did Vasudeva

leave Kamsa’s palace than Narada arrived on the scene. He told Kamsa: ‘Did you know that Nanda and the other men and women of Vraja, as well as those of the Yadava clan, are all gods and goddesses in human forms? Once I happened to be there at a meeting of the gods. There I came to know that they were making plans to kill you along with all your relatives and followers. You are very dear to me; so, as a well-wisher, I came to inform you. Now you do whatever you think proper.’ Kamsa was prompt in acting on Narada’s words. He deposed his father Ugrasena and assumed kingship, had Devaki and Vasudeva imprisoned, and began persecuting the Yadavas.

This incident would convince us that Narada was a cruel person, given to provoking ill-feeling and quarrel. That is why he is often called a piśuna - a slanderer, given to backbiting. But Narada is endowed with a vision and memory that is far deeper than that of an ordinary person. So he is able to act in harmony with imperceptible divine plans, and his actions have a subtle and mysterious quality.

In this case, Kirtiman and the other children of Vasudeva were the presiding deities of the eight quarters of the globe. They had to take human birth as a result of Brahma’s curse. They were to regain their godly states only after their human bodies were destroyed by their maternal uncle. Moreover, only when adharma, lawlessness, reaches a climax, and the devotees of the Lord start suffering torture, does Bhagavan appear on earth to protect his devotees by destroying the perpetrators of adharma. So, Narada was only being a voluntary participant in the cosmic drama. Similar altruistic motives may also be discovered in other acts of Narada.

A Man of Knowledge and a Teacher[edit]

Nothing in the three worlds is beyond Narada’s ken. In Vedic passages, we see him performing yajnas on behalf of kings. Once Valmiki asked Narada if he knew of any person who was perfect in every respect, and if such perfection was at all humanly possible. Narada told him of Ramachandra and also narrated the story of his entire life. This helped Valmiki pen the epic Ramayana.

We also find Narada present in Yudhishthira’s court at Indraprastha, describing the secret behind the birth of the terrible demons Hiranyaksha and Hiranyakashipu, which is ‘impossible even for the gods to know’. Kayadhu, mother of the great devotee Prahlada was provided shelter by Narada in his ashrama while she was expecting. Narada would tell Kayadhu the mysteries of religion, the distinction between Self and non-Self, as well as the essentials of true devotion. The teachings were also for Prahlada, who was still in his mother’s womb:

Rsih kārunikastasyāh prādādubhayamīśvaram; Dharmasya tattvam jñānam ca māmapyuddiśya nirmalam.

Having me [Prahlada] also in mind, the merciful sage of great spiritual power imparted to her instructions regarding the flawless path of devotion and the enlightenment conveyed by it.[6]

Later, Prahlada also recalled that ‘owing to the blessings of the sage, those teachings have ever remained fresh in my memory; rsinānugrhītam mām nādhunāpyajahāt smrtih’ [7]

Narada is also the preceptor of another famous devotee: Dhruva. When he was denied the right to sit on his father’s lap by his stepmother Suruchi, Dhruva rushed back to his mother Suniti in tears. Poor Suniti was not a favourite with the king, and all that she could say by way of consolation to Dhruva was this: ‘Ārādhayādhoksaja-pāda-padmam yadīcchase’dhyāsanam-uttamo yathā; if you wish to sit (on your father’s lap) like Uttama (your stepbrother), then worship the lotus feet of Vishnu’ [8]

Dhruva took his mother’s advice seriously and, controlling his mind, left his father’s palace in search of Vishnu. Narada, omniscient that he is, came to know of Dhruva’s leaving home. He met him on the way and tried to dissuade him from undertaking all the austerity needed to secure the grace of Vishnu, saying: ‘Happiness and unhappiness are due to one’s past karma, so one should remain satisfied with one’s fate; one should not feel jealous of persons with superior qualities; it is difficult to serve and propitiate the Lord, you can undertake all the necessary spiritual practices once you come of age.’ But far from being dissuaded, Dhruva sought Narada’s help in his search for the Supreme Being:

Padam tribhuvanotkrstam jigīsoh sādhuvartma me; Brūhyasmat-pitrbhir-brahman anyair-apyanadhisthitam.

O great one! I desire to attain to that state which is the most excellent in the three worlds, and which has not been achieved by my forefathers or by anybody else. Please tell me the best way to achieve this [9]

Pleased with Dhruva’s resolve, Narada initiated him with the mantra ‘Om namo bhagavate vāsudevāya’, advised him to go to Madhuvana on the banks of the Yamuna ‘where Hari’s presence is palpable at all times’, and also instructed him how to undertake contemplation, worship, and other spiritual practices. Equipped with Narada’s instructions, Dhruva undertook intense tapas and was soon blessed with a vision of the Divine.

Counselor to Yudhishthira and Krishna[edit]

When Yudhishthira occupied the throne at the magnificent new court constructed at Indraprastha by Maya, Narada decided to visit him. At Yudhishthira’s request, Narada described to him the excellences of some famous celestial courts: those of Indra, the king of the gods; Yama, the god of death; Brahma, the grandsire; Kubera, the king of treasures; and Varuna, the lord of the waters. In the course of conversation, Narada also advised Yudhisthira on the science of politics, administration, diplomacy, and warfare. Narada’s political counsels would appear remarkable even in our days of democracy and globalization.

Narada’s is a multifaceted character that largely remains incomprehensible. All the same, Narada is loved by all. He is a beloved devotee of the Lord. He is the author of a number of texts like the Narada Bhakti Sutra, the Narada Pancharatra, and the Narada Samhita. Above all, Narada is a friend, philosopher, and guide to those who need help to find their way out of distressing situations. Even Krishna, the famous teacher of the Bhagavad Gita, sought Narada’s advice when his own kinsmen—the Yadavas, Vrishnis, Bhojas, and Andhakas—were causing him great worry through their unruly behavior and persistent mutual quarrels. He expressed his anxiety to Narada: ‘It is not proper to disclose one’s secrets to a stupid friend, nor to fickle souls, even though they be learned. You are my beloved, and also a great friend. You have a sharp mind; so please tell me what I should do about my relatives who grind my heart with their cruel talk, even as one grinds sticks for fire.’ Narada tells Krishna that this was a ‘domestic problem’. Krishna helped his clansmen by getting them land and wealth; and this turned their heads. He could not possibly take these away without provoking bloodshed. ‘Use then a weapon,’ said Narada, ‘that is not made of steel, that is very mild, and yet capable of piercing all hearts.’ When Krishna inquired what that weapon was, Narada replied: ‘The giving of food to the best of your ability, forgiveness, sincerity, mildness, and honouring those who deserve to be honoured—these constitute a powerful weapon not made of steel. Turn the hearts and minds of your kinsmen with soft words; for none who is not great and pure at heart, and backed by great achievements and reliable friends, can bear a heavy burden.’[10]

Narada in Krishna’s Eyes[edit]

Yudhishthira asked Bhishma, who was lying on the ‘bed of arrows’ on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, to tell him about one ‘who is dear to all, who gladdens all, and who is endowed with all merit and accomplishment’. Bhishma recounted Krishna’s words to Ugrasena, who wanted to know why everyone spoke so highly of Narada: ‘Narada is as learned in the scriptures as he is noble in conduct; yet he is not proud or boastful. Anger, impudence, fear, and procrastination have left him for good. That is why he is adored by all. He never deviates from his word, or overpowered by passion or greed; so he deserves worship. High honour is paid to him because he is a man of spiritual knowledge, and is energetic, forgiving, self-possessed, simple, truthful, intelligent, and modest. He is liked because he is austere, good-natured, eloquent, soft spoken, decorous, pure, amiable, devoid of malice, and an expert in music. He always does good to others and so is untouched by sin. He never finds pleasure in other’s misfortunes, and secures his ends with the aid of scriptural wisdom and knowledge of past events; hence he is universally held in high regard. He seeks to overcome all worldly desires by chanting the Vedas and attending to the Puranas. He is a great renouncer. He grants no special favours, nor does he despise anyone. He dispenses knowledge equally to all and speaks according to the temperament and needs of his listener, so his conversation is delightful. He is vastly learned, wise, free from passion, deceit, laziness, greed, and anger; hence he is venerated. He is a man of unflinching devotion. He has gone beyond delusion. He does not strive to achieve wealth or objects of passion. Though totally detached, he takes a keen interest in the affairs of the world. He observes the diversity of human thought and behaviour, but never speaks ill of anybody. He always strives to reconcile people and does not indulge in self-praise. He disregards no science, nor does he repudiate other faiths; but he lives by his own standards of morality. He never wastes a moment and is always a master of his own self. He has earned Self-knowledge through much labor, and he does not refrain from the practice of samadhi. He is not without a sense of shame and is always open to instruction from others, if that would add to his perfection. Never does he divulge others’ secrets, for his mind is always detached, his intellect firm, and his heart unmoved by gain or loss. Who would not make this paragon of virtue—efficient, holy, provident, and tactful—a beloved friend?’ [11]

It is small wonder, therefore, that the Bhagavata also eulogizes Narada:

Aho devarṣirdhanyo’yaṃ yatkīrtiṃ śārṅgadhanvanaḥ; GāyanmādyannidaṃTantryā ramayatyāturaṃ jagat.

Blessed is this divine sage Narada! For singing the divine glories of the Lord to the accompaniment of his veena, he himself is ever inebriated with divine love, and he enlivens with joy the hearts of beings distressed by the woes of the world.[12]

Narada’s Political Counsels[edit]

Narada [to Yudhishthira]: ‘Is the wealth that you earn spent on proper objects? Does your mind take pleasure in virtue? Are you enjoying the pleasures of life? Has your mind avoided sinking under their weight?… Ever devoted to the good of all, conversant as you are with the timeliness of all things, do you pursue dharma, artha, kama, and moksha, dividing your time judiciously?

‘The seven principal officers of your state—the governor of the citadel, the commander of the forces, the chief judge, the general in command of interior affairs, the chief priest, the chief physician, and the chief astrologer—have not, I hope, succumbed to the influence of your foes, nor have they, I hope, been idle in consequence of the wealth they have earned. They are, I hope, all obedient to you. Your counsels, I hope, are never divulged by your trusted spies, by yourself, or by your ministers. You ascertain, I hope, what your friends, enemies, and strangers are up to. Do you make peace and war at proper times? Do you observe neutrality towards strangers and persons who are neutral towards you? The victories of kings can be attributed to good counsels. Is your kingdom protected by ministers learned in the Shastras who keep their own counsel?

‘Do you never let agriculturists out of your sight? Are they free of fear in approaching you? Do you execute your plans through people who are trusted, incorruptible, and possessed of practical experience? Are your forts filled with wealth, food, weapons, water, engines and instruments, as also with engineers and bowmen? Even a single minister that is intelligent, brave, self-controlled, and possessed of wisdom and judgment, is capable of conferring the highest prosperity on a king or his son; do you have even one such minister? Do you try to know everything about the eighteen tirthas of your enemy and the fifteen of your own by means of three spies, all unacquainted with one another? Is the priest you honor possessed of humility and renown, born of noble lineage, and free from jealousy and illiberality? Have respectable servants been employed by you in offices that are respectable, indifferent ones in offices that are indifferent, and inferior ones in offices that are low? Have you appointed to high offices ministers that are guileless and of good conduct for generations and above the common run? Do you avoid oppressing people with cruel and severe punishments?

‘Is the commander of your forces confident, brave, intelligent, patient, well-behaved, of good birth, devoted to you, and competent? Do you treat with consideration and regard the chief officers of your army that are skilled, forward[-looking], well-behaved, and powerful? Do you give your troops the appointed rations and pay at the proper time? I hope no single person of unbridled passions is allowed to manage a number of concerns pertaining to the army? Is any of your servants who has accomplished well a particular business by employing a special ability disappointed in obtaining from you a little special regard, and an increase in food and pay? I hope you reward persons of learning, and humility, and skill in every kind of knowledge with gifts of wealth and honor proportionate to their qualifications? Do you support the wives and children of men who have given their lives for you and have been distressed on your account? Do you cherish with paternal affection the enemy that has been weakened or that seeks refuge in you, having been vanquished in battle? Are you equal to all, and can everyone approach you as if you were their father and mother?

‘Is your expenditure always covered by a fourth, a third, or half of your income?—Do your accountants and clerks apprise you every day, in the forenoon, of your income and expenditure? Do you take care not to dismiss servants that are skilled in their jobs, popular, and devoted to your welfare for no fault of theirs? Do you employ in your business people that are not thievish, or covetous, or minors, or women? Are the agriculturists in your kingdom contented? Are large tanks and lakes constructed all over your kingdom at proper distances so that agriculture is not exclusively dependent on showers from the heavens? Are agriculturists in your kingdom wanting in either seed or food? Do you grant generous loans [of seed] to the tillers? Are the four professions of agriculture, trade, cattle-rearing, and lending at interest carried on by honest men? Do the five brave and wise men, employed in the five offices of protecting the city, the citadel, the merchants, and the agriculturists, and of punishing criminals, always benefit your kingdom by working in unison? For the protection of your cities, have the villages been made like towns, and the hamlets and village outskirts like villages? Are all these entirely under your supervision and sway? Are thieves and robbers that sack your towns pursued by your police over the even and uneven parts of your kingdom? I hope no well-behaved, pure-souled, and respected person is ever ruined and his life taken, on false charge or theft by ministers that are ignorant of the shastra and acting out of greed.

‘I hope your ministers are never won over by bribes, nor that they wrongly decide disputes that arise between the rich and the poor. Do you keep yourself free from the fourteen vices of kings: atheism, untruthfulness, anger, lack of caution, procrastination, avoidance of the wise, idleness, restlessness of mind, seeking counsel from only one person, seeking advice from people unacquainted with the economics of profit, abandonment of settled plans, divulgence of plans, non-accomplishment of projects, and action without reflection? Are merchants treated with consideration in your capital and kingdom; are they allowed to trade without being deceived?

Do you always listen to instructions on dharma and artha from the elderly who are experienced in economics? ‘Do you give regularly to the artisans and artists employed by you the materials needed for their works as well as their due wages? Do you examine their works, appreciate them before good men, and reward them, having shown them due respect? Acquainted with every duty, do you cherish like a father the blind, the dumb, the lame, the deformed, the friendless, and the ascetics that have no homes? Have you overcome these six evils: sleep, idleness, fear, anger, weakness of mind, and procrastination?’ [13]

References[edit]

- ↑ Bhagavata, 1.5.4.

- ↑ Bhagavata, 1.5.13

- ↑ See Bhagavata, 1.5–6.

- ↑ Chhandogya Upanishad, 7.1.1–3.

- ↑ M, The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, trans. Swami Nikhilananda (Chennai: Ramakrishna Math,2002), 368.

- ↑ Bhagavata, 7.7.15.

- ↑ Bhagavata 7.7.16

- ↑ Bhagavata 4.8.19

- ↑ Bhagavata 4.8.37

- ↑ Mahabharata, ‘Shanti Parva’, 81.

- ↑ Mahabharata, ‘Shanti Parva’, 230; see also Swami Tyagisananda, Aphorisms on the Gospel of Divine Love or Narada Bhakti Sutra (Madras: Ramakrishna Math, 1943), 27–30.

- ↑ Bhagavata, 1.6.39.

- ↑ Adapted from Mahabharata, 'Sabha Parva', 5; trans. Kisari Mohan Ganguli

- Originally published as "Narada: The Sage Celestial" by Prabhuddha Bharata November 2008 edition

. Reprinted with permission.