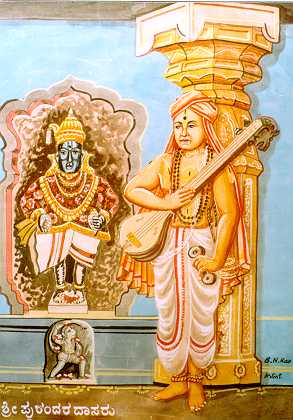

Purandara Dasa

Purandara Dasa was born to a pawnbroker named Varadappa Nayaka. Varadappa Nayaka and his wife Lakshmi Bai had been childless for several years, and finally, after praying to Lord Srinivasa of Tirupati, they became proud parents of a child whom they called Srinivasa. The family are supposed to have hailed from Pandarapur in modern day Maharashtra but Purandara Dasa lived in Hampi during the latter part of his life.

Srinivasa Nayaka grew up and entered his father's business. However, unlike his father, he was a miser, so much so that it is said that he even baulked at spending money on treatment for his father's illness. His wife Saraswathi bai was the opposite: always wishing to contribute to charity much to the displeasure of her husband.

One day, Lord Vishnu in the guise of a poor priest visited Srinivasa Nayaka's shop who wanted some alms to perform the thread ceremony for his son. Srinivasa Nayaka, being a miser, asked him to return the following day, and kept the Brahmin coming for another six months. Finally, fed up with the Brahmin's persistence, he gave him one fake coin that he played with as a child. Vishnu as the priest then told Srinivasa's wife Saraswathi the pitiful story of how a miserly pawnbroker made him come to his shop every day for six months only to give him a fake coin in the end. Saraswathi's heart melted and she gave the Brahmin her nose ring as alms (a gift from her parents and thus not something that she got from her husband). The Brahmin promptly took the nose ring back to Srinivasa Nayaka's shop, where he wanted to pawn it for money. The pawnbroker recognized it, however, so he locked it up in his safe and hurried home. He demanded that Saraswathi produce her nose ring immediately. Struck with fear, Saraswathi locked herself in the kitchen and tried to swallow poison. Miraculously, the nose ring dropped from the heavens into her cup of poison and she was able to produce it for her husband. Upon returning to his shop, he opened the safe, only to find that the nose ring in the safe had vanished. This put his mind into a turmoil. After deep thought, he came to the conclusion that the brahmin was none other than Lord Shri Purandara Vitthala Himself. He recalled all the incidents that had transpired in the previous six months. Wonderstruck, he was ashamed of his miserliness, Srinivasa Nayaka decided to renounce all material belongings and become a dasa (servant)of god. Thus, Srinivasa Nayaka came to be Purandara Dasa. In gratitude for this event, he would later compose a song dedicated to his wife, for having shown him the path to God. From that day onwards he became a devotee of Shri Hari. The once Navkoti Narayana became a Narayana bhakta, the hands which sported gold and diamond rings now played the tamboora, the neck which used to be resplendent with golden chains now housed the tulasi mAla. The man who had turned away countless people away, now himself went around collecting alms and living the life of a mendicant. The Nayaka who would have lived and died an inconsequential life became the Great Purandaradasa, loved and revered even centuries after his death.