Talk:Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization

By Swami Harshananda, Himanshu Bhatt, and Krishna Maheshwari

The Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization or the Saraswati-Sindhu Sabhyata, also known as Indus-Sarasvati Civilization[1], Indus-Ghaggar-Hakra Civilization[2], Sapta-Sindhu[3] (or Sapta-Sindhava), and formerly known as the Indus Valley Civilization, was the first civilization to implement architectural designs for creating entire cities. The first cities found of this ancient civilization were Harappa and Mohenjo Daro in modern day Sindh (Pakistan), and Dholavira and Lothal in modern Gujarat. It is 8,000 years old[4] or more. Its extent was from Daimabad in the south, Mandi in the east, Sutkagan Dor in the west, to either Burzahom or Shortugai in the north. Because Bhirrana is the oldest documented settlement from the civilization, it is most likely that it was also where the civilization first began and spread from. it is also important to note that Rakhigarhi (also along the Sarasvati) was the largest of the civilization's settlements, measuring around 300 hectares (whereas the 2nd largest settlement is Mehrgarh at 200 ha.)

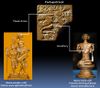

The discovered artifacts (found in the early 20th century) provide a good idea of what religious customs of the time were like. Three lingas dating around 5,000 years old were found in Harappa, the famous Pasupati Seal was found there too, while Mohenjo Daro contained the ceremonial Great Bath, fire altars were found in Kalibangan, and Dholavira contains a ceremonial well for purification purposes.

Massive and constant flooding, due to sea levels rising, was the major reason for abandoning the cities and relocating to other urban centers. From the devastation of flooding, its residents migrated and many of the Sindhi migrants were the ones who had migrated from their homeland in the Indian Subcontinent to the Middle East and Europe. Some of its residents had also migrated by sail in a 30° pathway fron Mohenjo Daro to Giza (Egypt), Machu Pichu (Peru), and Easter Island. In the latter two are where Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization scripts were found.

The Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization and culture represents the Rig Vedic culture.

Timelines of the Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization[edit]

The Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization, in its urban or “Mature” phase, is dated to 2600–1900 BCE. However, it was preceded by a millennium-long “Early” phase, which saw the convergence of important concepts and technologies, and had further antecedents reaching back to about 7000 BCE, a Neolithic culture at Mehargarh, which shows a continuous evolution all the way to the Mature phase.

The oldest site of the civilization is Bhirrana (in modern-day Haryana), which was actively inhabited approximately between 8000-2600 BCE. S.R. Rao states the following and is supported by Sarkar et al. [5], who also refer to a proposal by Possehl [6][7] and to various radiocarbon dates from other sites:

7000 – 3300 BCE = Pre-Harappan (Mehargarh)

3300 – 2600 BCE = Early Harappan

2600 - 2500 BCE = Early Mature Harappan

2500 – 1900 BCE = Mature Harappan

1900 – 1300 BCE = Post-urban Harappan.[8]

By 1900 BCE, the civilization started breaking down. The archeological evidence shows consequent migration of the population eastwards. Mohenjo-Daro completely vanished by 1900 BCE but Harappa shows continuity till about 1300 BCE.

Some other sites in Gujarat show continuity till 1000 BCE[9]. Many aspects and cultural practices, including the city building plan, of the Harappans continued till the historic times as evidenced in the excavation of a 600 BCE city of Shishupalgarh by B. B. Lal [10] and its incorporation in the Arthaśāstra of Kautilya [11], who apparently was the mentor and teacher of Chandragupta Maurya.

- Proposed Reasons for Decline Beginning in Late Harappan Phase

| Cause(s) | Scholar(s) |

|---|---|

| Change in River Course | Dales, M.S. Vatsa, H.T. Lambrick |

| Drying of Ghaggar (Sarasvati) and Increasing Airidity | D.P. Agarwal and Sood |

| Earthquake | Rakes and Dales |

| Ecological Disturbance | Fairchild |

| Flood | Macay, S.R. Rao |

| Low Rainfall | Stein |

| Natural Calamities | K.A.R. Kennedy |

Archaeological Sites in India[edit]

Further excavations over the next few decades revealed roughly 50 sites along the Indus and 1,000+ along the Sarasvati belonged to this civilization[12]. However, almost all the findings cognate to the discoveries at other sites indicating that they span a single civilization.

Over 1,400 Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization sites have been discovered, of which 925 sites are in India and 475 sites in Pakistan, as well as some sites in Afghanistan which are believed to have been trading colonies established by people of the Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization.

Overview of Discoveries[edit]

The archaeological findings at various levels or depths have been assigned to different periods of history. The oldest of these findings is from 7000 BCE and the most recent one is from 2000 BCE. These discoveries reveal that the Harappan culture spread across more than 1,000 sites was a Vedic culture with findings that reference practices that continue to this day in modern day India.

- Amalgamation of Local Cultures into Common Civilization

| Date | Culture (Rao 2005) |

Period (Dikshit 2013) |

Phase (Sarkar 2016) |

Conventional date (HP) | Harappan Phase | Conventional date (Era) | Era |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7500-6000 BCE | Period IA: Hakra Wares Culture | Pre-Harappan Hakra Period (Neolithic) | Pre-Harappan | 7000-3300 BCE | Pre-Harappan | c.7000-c.4500 BCE | Early Food Producing Era |

| 6000-4500 BCE | Period IB: Early Harappan | Transitional Period | Early Harappan | ||||

| 4500-3000 BCE | Period IIA: Early Mature Harappan | Early Harappan Period | Early Mature Harappan | c.4500-2600 BCE | Regionalisation Era | ||

| 3300-2600 BCE | Early Harappan | ||||||

| 3000-1800 BCE | Period IIB: Mature Harappan | Mature Harappan Period | Mature Harappan | ||||

| 2600-1900 BCE | Mature Harappan | 2600-1900 BCE | Integration Era | ||||

| 1800-1600 BCE (1800-800 BCE) |

Late Harappan Period | Late Harappan Period | 1900-1300 BCE | Late Harappan | 1900-1300 | Localisation Era |

- Localization of Civilization

| Date | Main phase | Subphase | Harappan Phase | Era |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ca. 4000 - 3500 BCE | Formative Phase | e.g., Mehrgarh-IV-V | Pre-Harappan | Regionalisation Era |

| ca. 3500 - 2800 BCE | Early Phase | e.g., Kalibangan-I | Early Harappan | |

| ca. 2800 - 2600 BCE | Period of Transition | e.g., Dholavira-III | ||

| ca. 2600 - 1900 BCE | Mature Phase | e.g., Harappa-III, Kalibangan-II | Mature Harappan | Integration Era |

| ca. 1900 - 1500 BCE | Late Phase | e.g., Cemetery H, Jhukar | Late Harappan | Localisation Era |

| ca. 1500 - 1400 BCE | Final Phase | e.g., Dholavira |

- Concordance of Periodisations

| Dates | Main Phase | Mehrgarh phases | Harappan phases | Other phases | Era |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7000–5500 BCE | Pre-Harappan | Mehrgarh I (aceramic Neolithic) |

Early Food Producing Era | ||

| 5500–3300 BCE | Pre-Harappan/Early Harappan | Mehrgarh II-VI (ceramic Neolithic) |

Regionalisation Era c.4000-2500/2300 BCE (Shaffer) c.5000-3200 BCE (Coningham & Young) | ||

| 3300–2800 BCE | Early Harappan c.3300-2800 BCE c.5000-2800 BCE (Kenoyer) |

Harappan 1 (Ravi Phase; Hakra Ware) |

|||

| 2800–2600 BCE | Mehrgarh VII | Harappan 2 (Kot Diji Phase, Nausharo I) |

|||

| 2600–2450 BCE | Mature Harappan (Indus Valley Civilisation) | Harappan 3A (Nausharo II) | Integration Era | ||

| 2450–2200 BCE | Harappan 3B | ||||

| 2200–1900 BCE | Harappan 3C | ||||

| 1900–1700 BCE | Late Harappan | Harappan 4 | Cemetery H Ochre Coloured Pottery |

Localisation Era | |

| 1700–1300 BCE | Harappan 5 | ||||

| 1300–600 BCE | Post-Harappan Iron Age India |

Painted Grey Ware (1200-600 BCE) Vedic period (c.1500-500 BCE) |

Regionalisation c.1200-300 BCE (Kenoyer) c.1500-600 BCE (Coningham & Young) | ||

| 600-300 BCE | Northern Black Polished Ware (Iron Age)(700-200 BCE) Second urbanisation (c.500-200 BCE) |

Integration |

Significance of Sarasvati River[edit]

- See also: Sarasvati River

After having analyzed geophysical features, combined with satellite imagery, further elaborated by the stories of the Sarasvati River within northern Indian cultures, the consensus among geoscientists and archaeologists is that the Gaggar-Hakra was the Sarasvati, and that the now-extinct Nara (upon which the Nara Canal in Sindh was built) was a part of the river too.

The disintegration of the Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization can be traced to the gradual disintegration and erosion. This explains areas in which the Indus and its tributaries did not flow through broke away from the Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization first. In Gujarat and southeastern Sindh, in which the Indus did not flow through or have any impact on, flourished in the peak of the Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization. The Sarasvati was not only able to connect that region, but also some cities on the Gangetic Basin, including settlements now in the statement of Uttar Pradesh (Alamgirpur, Bargaon, Hulas, Mandi, Sanauli, and Sothi.) Of the 10 most important Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization sites, only 3 (Harappa, Mohenjo Daro, Chanhu Daro) are along the Indus River, while 1 (Lothal) lies on the shoreline, and the other 6 (Rakhigarhi, Banawali, Kalibangan, Dholavira, Surkotada) are along the tract of the Sarasvati. Further, the Rann of Kutch was inundated with water during the Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization era as is it now, even without receiving water from the ocean or another river. This is because of the supply of water that came from the Sarasvati River, which passed through the Rann while making its way into the ocean.

The erosion of rivers as they have "shifted underground," have continued being used in some cases[13]. The Nara was a part of the Sarasvati which has become the modern-day Nara Canal. This erosion occurs due to tectonic uplift, especially due to Tectonic–climatic interaction.

After the river’s decline, the change in the epicentre of Indian civilization from the Sarasvati river to the Ganga is seen implicitly in the Puranic story of the descent of Ganga and more clearer in the Mahabharata (Vana Parva, chapter 85) which states that in the Treta Yuga Puskara was the holiest tirtha, while in Dvapara it was Kurukshetra, and in the Kali it is Prayaga.[14] Prayaga is at the confluence of the Ganga and Yamuna. Both it and Varanasi are considered the holiest places of Hinduism, and their pilgrimages, known as Kumbh Mela, are the largest human gathering on Earth (more so than Jerusalem and Mecca.) So why did Prayaga become the seat of chief Hinduism during the Mahabharata War's era?: Because a part of the Sarasvati was still flowing through the city (while in some areas it had already eroded), along with the Ganga and Yamuna rivers.

Denial of Existence[edit]

Writers have opposed the idea of the Ghaggar-Hakra and its former Nara segment, being parts of the no fragmented Sarasvati River. Their reason for doing so was to discredit Hinduism by portraying the holiest land of the Rig Veda compilers, known as Brahmavarta (situation between the Sarasvati and its Drishadwati tributary, as being outside of India (thereby depicting Hinduism and Aryans as non-Indian in origin.) Historically, supporters of this have been Islamists (both Indian and foreign), Eurocentrists (i.e., White nationalists, and imperialists), and Indian liberals (i.e., Marxists, certain Dalit Neobuddhists, staunch atheistic Dravidianists.)

With more and more investigation from both Indian and international researchers, this denial has become very difficult, especially as the Ghaggar-Hakra actually does match every geophysical description within texts, and because it actually was very significant for the establishment and decline of the Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization.

Restoration Efforts[edit]

"To me the project is much more than religious...Every year farmers in the district lose crop over a vast stretch of cultivated area because of floods in the Somb. If we can divert the waters, as much 10,000 acres of land can be reclaimed." - Gagandeep Singh, Haryana civil services officer and volunteer of revival project

The point of origin of the fragmented river is believed to be the base of the Shivalik Mountains and has been called Saraswati Udgam Sthal. Resurrecting this river would be helpful to farmers in particular because it would save their crops, and others because they would have a new drinking souce. Some notable Jains are part of the revivalist effort as well.[15][16]

Harappa[edit]

The Harappa town was a square of about 1.5 kms. (0.9 mile) on each side and 4.8 kms. (3 miles) in circumference. It was laid out in a grid pattern of the streets. The houses were built of burnt bricks whose dimensions conformed strictly to the Kāśyapa Samhitā. The dimensions of the bricks were 11.75" x 5.25" x 7.5" and two other sizes. The houses had only one main door for entrance fixed on the side lanes. There were courtyards inside and the windows opened to the streets. Small houses had just two rooms whereas the bigger ones could have even twenty five rooms. Bathrooms, latrines and sanitary arrangements were very good. Apart from bricks and mortar, wood was generously used not only for construction purposes but also for a wide range of furniture like cots, chairs, stools, tables and easy-chairs. Firewood and charcoal were in use in the domestic stoves. Rooms were often set apart for the purpose of worship.

Roads were straight and well maintained. Special chambers had been constructed for the collection and disposal of garbage. One of the most striking features of the Harappa town was its big granary or warehouse. There were 12 granaries arranged in two parallel rows with proper arrangements for ventilation and passages of approach. There were grain millers built on brick platforms where wooden pestles were used for crushing the grains.

Mohenjo Dāro[edit]

Mohenjo Dāro means ‘the mound of the dead’. It is situated on the west bank of the Indus river about 600 kms. (375 miles) to the south-west of Harappa. This site is larger and better preserved than Harappa. The layout is strikingly similar to that of Harappa.

The chief attraction of this site is ‘The great Bath.’ It was built of brick set in gypsum mortar with a damp-proof course of bitumen. The dimensions were 54 by 33 meters (177 by 108 ft.). The outer walls were massive having thickness of 2 to 2.5 meters (7 to 8 ft.). In the center there was an open paved quadrangle with verandahs on the four sides. At the back of the verandahs, galleries and rooms were situated. In the center of the paved quadrangle there was a large swimming bath of 11.8 by 7 meters (39 by 23 ft.) dimensions. The swimming pool was lined by finely dressed brick laid in gypsum mortar and covered with bitumen. Steps leading to a low platform were also constructed for the convenience of the bathers. Arrangements for some kind of steam-bath were also found.

Dholavira[edit]

- Main article: Dholavira and Buddhism

Dholavira matches the descriptions of the Sukhavati paradise mentioned in Buddhist scriptures. It is tis Buddha-kshetra in which Amitabha resided, and in which his disciples Alokiteshvar and Vajrapani lived with him before establishing their own Buddha-kshetras.

Dholavira was also the Sukha city of Varuna.

Lothal[edit]

Add summary here

Ganweriwala[edit]

Selection of uncovered cities[edit]

| Site | District | Province/State | Modern Country | River Source(s) | Active Era | Hectares | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alamgirpur | Meerut | Uttar Pradesh | India | Yamuna, Hindan | 3300 - 1300 BCE | 10 | Impression of cloth on trough |

| Allahdino | Karachi | Sindh | Pakistan | Indus | ? - 2000 BCE | 1.4 | Floor tiles of a house have been discovered at this site[17] |

| Amri | Dadu | Sindh | Pakistan | Indus | 3500 - 2400 BCE[18] | 3.5 - 4 | Remains of rhinoceros |

| Babar Kot | Saurashtra | Gujarat | India | Amreli | A stone fortification wall,[19] plant remains of millets & gram.[19][20] | ||

| Balu | Kaithal | Haryana | India | Sarasvati | Earliest evidence of garlic.[21] Several plant remains were found here include various types of barley, wheat, rice, horse gram, green gram, various types of a pea, sesamum, melon, watermelon, grapes, dates, garlic, etc. (Saraswat and Pokharia - 2001-2)[19] which is comparable to a nearby Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization site Kunal, Haryana revealed remains of rice (probably wild). | ||

| Banawali | Fatehabad | Haryana | India | Sarasvati, Rangoi | 2500 - 1450 BCE | 16 | Barley, terracotta figure of plough |

| Bara | Rupnagar | Punjab | India | Sarasvati | 2000 - ? BCE | 4 - 8 | |

| Bargaon | Saharanpur[22] | Uttar Pradesh | India | Yamuna, Hindan | |||

| Baror | Sri Ganganagar | Rajasthan | India | Sarasvati | Human skeleton, ornaments, 5 meter long and 3 meter clay oven, a pitcher filled with 8,000 pearls[23] | ||

| Bet Dwarka | Devbhoomi Dwarka | Gujarat | India | Gomti | ? - 1500 BCE | Late Harappan seal, inscribed jar, the mould of coppersmith, a copper fishhook[24][25] | |

| Bhagatrav | Bharuch | Gujarat | India | Tapi | |||

| Bhagwanpur (or Baghpur) | Kurukshetra | Haryana | India | Sarasvati | 1700 - 1000 BCE | ||

| Bhirrana | Fatehabad | Haryana | India | Sarasvati | 7500 - 800 BCE | Graffiti of a dancing girl on pottery, which resembles a dancing girl statue found at Mohenjo Daro | |

| Chak 86 | Ganganagar | Rajasthan | India | Sarasvati | |||

| Chanhu Daro | Nawabshah | Sindh | Pakistan | Indus | 4000 - 1700 BCE | Bead making factory, use of lipstick,[26] only Indus site without a citadel | |

| Chapuwala | Cholistan Desert | Punjab | Pakistan | Sarasvati | unexcavated 9.6 hectares[27] | ||

| Daimabad | Ahmadnagar | Maharashtra | India | Pravara | 2300 - 1800 BCE | 20 | A sculpture of a bronze chariot, 45 cm long and 16 cm wide, yoked to two oxen, driven by a man 16 cm high standing in it; and three other bronze sculptures.[28] Southernmost Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization site |

| Daulatpur | Hisar | Haryana | India | Drishadvati | |||

| Dhalewan | Mansa | Punjab | India | Sarasvati | |||

| Desalpur | Kutch | Gujarat | India | Sarasvati, Rann of Kutch | Massive stone fortification, Harappan pottery, three script bearing seals; one of steatite, one of copper and one of terracotta.[29] | ||

| Dholavira | Kutch | Gujarat | India | Sarasvati, Rann of Kutch | 3500 - 1450 BCE | 47 | Figure of chariot tied to a pair of bullocks and driven by a nude human, Water harvesting and number of reservoirs, use of rocks for constructions |

| Farmana | Rohtak | Haryana | India | Sarasvati | Largest burial site of Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization, with 65 burials,found in India | ||

| Gamanwala | Bhawalpur | Punjab | Pakistan | Sarasvati | 27.3 | ||

| Ganweriwala | Bhawalpur | Punjab | Pakistan | Sarasvati | 2500 - ? BCE | 81.5 | Equidistant from both Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, it is near a dry bed of the former Ghaggar River. It is a site of almost the same size as Mahenjo Daro. It may have been the third major center in the Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization as it is near to the copper-rich mines in Rajasthan. |

| Ghaligay | Swat | Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa | Pakistan | Swat | 2000 - ? BCE | ||

| Girawar | Rohtak | Haryana | India | Sarasvati | |||

| Gola Dhoro | Kutch | Gujarat | India | Satalli | 2500-2000 BCE | 0.005 | Production of shell bangles, semi-precious beads, etc. |

| Harappa | Sahiwal | Punjab | Pakistan | Ravi | 2600 - 1300 BCE | 150 | Granaries, coffin burial, lot of artifacts, important Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization town, the first town which is excavated and studied in detail |

| Hisar Mound (inside Firoz Shah Palace) | Hisar | Haryana | India | Sarasvati | Unexcavated site | ||

| Hulas | Saharanpur | Uttar Pradesh | India | Yamuna, Hindan | 2000 - 1000 BCE | ||

| Jalilpur | Multan | Punjab | Pakistan | Ravi | |||

| Jalwali | Bikaner | Rajasthan | India | Sarasvati | 22.5 | ||

| Jognakhera | Kurukshetra | Haryana | India | Sarasvati | Copper smelting furnaces with copper slag and pot shards[30] | ||

| Juni Kuran | Kutch | Gujarat | India | Sarasvati, Rann of Kutch | fortified citadel, lower town, public gathering area[31] | ||

| Kaj | Gir Somnath | Gujarat | India | Shingavadi , Somat | Ceramic artifacts, including bowls. Ancient port.[32][33] | ||

| Kanjetar | Gir Somnath | Gujarat | India | Shingavadi , Somat | Single phase Harapppan site.[32][33] | ||

| Kalibangan | Hanumangarh | Rajasthan | India | Sarasvati | 3500 - 1750 BCE | Baked/burnt bangles, fire altars, small circular pits containing large urns and accompanied by pottery, bones of camel | |

| Kanmer | Kutch | Gujarat | India | Sarasvati, Rann of Kutch | |||

| Karanpura (near Bhadra) | Hanumangarh | Rajasthan | India | Sarasvati | 2600 - 1900 BCE | Skeleton of child, terracotta like pottery, bangles, seals similar to other Harappan sites [34] | |

| Khirasara | Kutch | Gujarat | India | Sarasvati, Khari, Rann of Kutch | 2600 - 2200 BCE | Ware House, Industrial area, gold, copper, semi-precious stone, shell objects, and weight hoards | |

| Kerala-no-dhoro (or Padri) | Saurashtra | Gujarat | India | Shetrunji | Salt production centre, by evaporating sea water | ||

| Kot Bala (or Balakot) | Lasbela | Balochistan | Pakistan | Winder, Wirhab | 2.8 | Earliest evidence of furnace, seaport | |

| Kot Diji | Khairpur | Sindh | Pakistan | Sarasvati, Indus | 3300 – 2600 BCE | ||

| Kotada Bhadli | Kutch | Gujarat | India | Sarasvati, Rann of Kutch | Fortification bastion few houses foundations[35] | ||

| Kotla | Rupnagar | Punjab | India | Sarasvati | 3300-1300 BCE | 4 - 8 | |

| Kudwala | Bahawalpur | Punjab | Pakistan | Sarasvati | 38.1 | ||

| Kunal | Fatehabad | Haryana | India | Sarasvati | 5000 - 2800 BCE | Earliest Pre-Harappan site, Copper smelting. | |

| Kuntasi | Rajkot | Gujarat | India | Phulki | 2200 - 1700 BCE | Small port | |

| Lakhanjo Daro | Sukkur | Sindh | Pakistan | Indus | 300 | major unexcavated site (greater than 300 hectares) | |

| Larkana | Larkana | Sindh | Pakistan | Indus | |||

| Loteshwar | Patan | Gujarat | India | Sarasvati, Khari, Rann of Kutch | Ancient archaeological site | ||

| Lothal | Ahmedabad | Gujarat | India | Tapi | 2400 - 1900 BCE | 4.5 | Bead making factory, dockyard, button seal, fire altars, painted jar, earliest cultivation of rice (1800 BCE) |

| Lurewala | Sargodha | Punjab | Pakistan | Indus | |||

| Manda | Jammu | Jammu & Kashmir | India | Chenab | Northernmost Harappan site in Himalayan foothills[36] | ||

| Malwan | Surat | Gujarat | India | Tapi | Southernmost Harappan site in India[37] | ||

| Mandi | Muzaffarnagar | Uttar Pradesh | India | Yamuna, Hindan | |||

| Mehrgarh | Kachi | Balochistan | Pakistan | Bolan | 7000 - 2000 BCE | 200 | Earliest agricultural community (7000-5000 BCE) |

| Mitathal | Bhiwani | Haryana | India | Sarasvati | |||

| Mohenjo Daro | Larkana | Sindh | Pakistan | Indus | 2500 - 1800 BCE | 81.5 | Great Bath (the biggest bath ghat), Great granary, Bronze dancing girl, Bearded man, terracotta toys, Bull seal, Pashupati seal, three cylindrical seals of the Mesopotamian type, a piece of woven cloth |

| Nageshwar | Kutch | Gujarat | India | Rann of Kutch | Shell working site[38] | ||

| Navinal | Kutch | Gujarat | India | Nagmati | [39] | ||

| Nausharo (near Dadhar) | Kachi | Balochistan | Pakistan | Bolan | 3000 - 1900 BCE | ||

| Ongar | Hyderabad | Sindh | Pakistan | Indus | |||

| Pabumath | Kutch | Gujarat | India | Sarasvati, Rann of Kutch | A large building complex, unicorn seal, shell bangles, beads, copper bangles, needles, antimony rods, steatite micro beads; pottery include large and medium size jars, beaker, dishes, dish-on-stand, perforated jars etc.; fine red pottery with black painted designs etc.[40] | ||

| Pathani Damb | Makran | Balochistan | Pakistan | Mula Nai | 100 | At 100 hectares, this has the potential to be another city[41] | |

| Pir Shah Jurio | Karachi | Sindh | Pakistan | Lyari, Malir | |||

| Pirak | Sibi | Balochistan | Pakistan | Nari | 1700 - 1000 BCE | ||

| Rakhigarhi | Hisar | Haryana | India | Sarasvati | 6500 - 1900 BCE | 350 | Terracotta wheels, toys, figurines, pottery. Large site, partially excavated. |

| Rangpur | Ahmedabad | Gujarat | India | Sukhbhadar | 3000 - 1000 BCE | Seaport | |

| Rehman Dheri | Dera Ismail Khan | Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | Pakistan | Zhob | 3300 - ? BCE | ||

| Rojdi | Rajkot | Gujarat | India | Bhadar, Aji, Nyari | 2500 - 1700 BCE | ||

| Rupar | Rupnagar | Punjab | India | Satluj | 4 - 8 | ||

| Sanauli[42] | Baghpat | Uttar Pradesh | India | Yamuna, Hindan | 1850 - 1550 BCE | 4 - 8 | Burial site with 125 burials found |

| Sheri Khan Tarakai | Bannu | Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa | Pakistan | Kurram, Gambila | 4000 - 3000 BCE | pottery, lithic artifact | |

| Shikarpur[43] | Kutch | Gujarat | India | Rann of Kutch | Food habit details of Harappans | ||

| Shortugai | Darqad | Takhar Province | Afghanistan | Amu | 2000 - ? BCE | ||

| Siddhuwala (near Derawar) | Bahawalpur | Punjab | Pakistan | Sarasvati | |||

| Siswal | Hisar | Haryana | India | Sarasvati | 3800 - 3200 BCE | 4 - 8 | it is very closely connected to the Sothi settlement. |

| Sokhta Koh | Makran | Balochistan | Pakistan | Shadi Kaur | 2600 - 1900 BCE | Pottery | |

| Sothi (near Baraut) | Bagpat | Uttar Pradesh | India | Yamuna, Hindan | 4600 - ? BCE | ||

| Surkotada | Kutch | Gujarat | India | Sarasvati, Rann of Kutch | 2100 - 1700 BCE | Bones of a horse (only site) | |

| Sutkagan Dor | Makran | Balochistan | Pakistan | Dashti, Gajo Kaur | 4.5 | Bangles of clay, Westernmost known site of Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization [44] | |

| Tarkhanewala Dera | Ganganagar | Rajasthan | India | Sarasvati | |||

| Vejalka | Botad | Gujarat | India | Ghelo, Kalubhar | 2300 - 2000 BCE | pottery |

World's Farming First Began Within the Civilization[edit]

Recent Genetic research has shown that the base DNA for all modern Indians dates back to 10,000 BCE[45].

It has been found that the peoples of the civilization had practiced agriculture implementing zebu (AKA Bos Indicus) cattle.[46]

Salient Features of Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization[edit]

Economy[edit]

The soldiers used weapons as bows, arrows, spears, axes, maces, catapults and slings. Weights and measures had been standardized. One scale discovered in the ruins had very accurate markings. Trade and commerce through land and sea were quite flourishing. Contacts had been well-established with Sumeria, Babylonia and Egypt for trade and commerce.

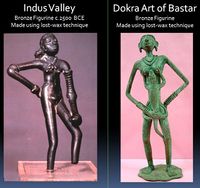

Culture and Arts[edit]

People were good at arts and crafts. This can be surmised through the various well-finished toys unearthed from the ruins. Chānhu Dāro town was famous for this. Music and dancing were also known to them. One can deduce from the figures found that the stringed instruments resembling a vīṇā (lute), cymbals, mṛdaṅga (drum) were in use. Pots and jars with various drawings and paintings have been recovered from the site. Various traditional Indian games like dice-game were known to them.

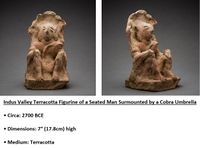

Religious Convictions[edit]

Worship of Shiva-Pashupati and his liṅga form, and Goddess Durgā, as well as spiritual symbolism of certain animals and trees like bison, fish, serpent, holy basil (tulasī) and peepul tree existed. A seal of people bowing before a tree was found in Ganweriwala.[47]

Presence of Shaivism[edit]

Many scholars such as Marshall associated Pashupati seal with Shiva because of its following features: (1) three faces (2) the attitude of yoga (3) ithyphallicism (4) connection with animals (5) pair of horns.[48] Shiva's association with the 'Pashupati seal' is that the seal reads "Lord of the Cattle" and "Lord of the animals" and Shiva has been described as both the lord of cattle and animals. The Pashupati seal also depicts the mendicant in the yogasana which is another attributed associated with Shiva from scriptures. In reference to the bulls that appear on the Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization seals, archeologists have linked them to Shiva as the bull is associated with him in scriptures. In the Rig Veda, Shiva (Rudra) is termed Vrishaba or "bull."[49] Shiva connection with the three heads on the Indus Valley yogi seal is that Shiva has been described and portrayed a three-headed in certain parts of history. For example, in the an Elora temple he is depicted with three heads.[50]

Rudra in the Vedas has been described as a hunter and tamer of animals.[51]

Standing meditative seal[edit]

A depiction called Ahmuvan has been found. It is of a standing figure who is given significance in the art by rays showing stemming from him, possibly indicating it is enlightened (having attained of possessing Moksha.) The standing yogic position in Hindu scriptures is associated with Shiva and has in earliest occurrences been mentioned as the sthanu asana. Shiva has repeatedly been called Sthanu in several scriptures.[52] That Shiva's standing pose is a meditative penance is clear from the pose being associated in Kalidas' literature as "Tapasvinah Sthanu"[53] and tapasvin is the term for a mendicant. Also Shiva as Sthanu in Kalidas' literature has been described as "Sthanu sthira-bhakti-yoga-sulabha" meaning "attainable through devotion yoga."[54] In modern Hindu yoga too the standing yoga asana is applied and called samabhanga asana[55] and tadasana.

Symbolism[edit]

- King-Priest Artifact

Apart from the Shiva icons, others present can be seen on depicted on tokens and the Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization walls.

The priestly meditative bust of Harappa depicts a clergyman in meditation. Apart from appearing as performing yoga, the figure is represented as the clergyman wearing a garment much like the garb of the sanyasi that goes over 1 shoulder. Further, the figure is wearing bands on his head and his biceps just like a Shaiva cleric that wears the vibhuti across his forehead and biceps.

Ascetics have also often been depicted wearing the mala (beads) on their biceps and marks on their foreheads. Wearing of iconography on their foreheads is a common practice for lay Hindus too, such as applying a tilak or Harimandira.

The dress of the Harappan figure is also notable because it looks like he is wearing a sanyasi robe, as it is also worn over just 1 shoulder.

- Swastikas

These emblems both clockwise and counter-clockwise are found across the Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization sites on tokens and walls. They are mentioned as early as the Rig Veda.

|

We invoke him who may bring us welfare. May the respected Indra guard our welfare, May the omniscient Pushan guard our welfare, May the Universal Creator guard our welfare, May the Great Protector bring us welfare. |

||

—Yajur Veda 25.18-19 | ||

Script or Language[edit]

One enigmatic aspect of the Sarasvatī-Sindhu Civilization is the script discovered on the various seals. The script remains to be deciphered.

Staple Diet[edit]

This civilization was more ancient and comprehensive than the ones of Egypt, Sumeria, Assyria and Mesopotamia. People were mostly vegetarians and many others consumed fish also. Apart from wheat, barley and rice, they grew several varieties of fruits and vegetables like pumpkin, dates and coconuts. They wore clothes made of cotton, jute and fibres.

Appearance of Men & Women[edit]

Several varieties of dressing hair were common among the women. The ornaments used to decorate them were girdles, ear-rings, bangles, necklaces, nose-rings, anklets, hairpins and beads. Turbans and head-dresses were used by women. The use of metals like gold, silver, lead, tin, copper, nickel, bronze and many precious stones like diamonds, rubies, emeralds and topaz was well-known to them. Shaving razors and highly polished mirrors were made out of these metals.

Cineration[edit]

Dead bodies were disposed through cremation, burial and the system of leaving the bodies to be eaten up by birds and animals seem to have existed. Bodies of babies and little children were generally interred in pots and then buried.

Related Articles[edit]

External Resources[edit]

- "Decoding the INDUS VALLEY SCRIPT" By Kak, Subhash

- "Indus era 8,000 years old, not 5,500; ended because of weaker monsoon" By Jhimli Mukherjee Pandey | TNN | May 29, 2016

- “Horses Are Indigenous To India; Here Are The Archaeological Evidences”

- “Dwarka – Pre-Harappan City That Could Rewrite The History Of The World” By A. Sutherland | AncientPages.com | August 19, 2014

- “Notes for Arts of the Indus Valley Civilization” | Art and Culture | UPSC | August 31, 2019

- “2,700 Year Old Yogi in Samadhi Found in Indus Valley” | June 7, 2016

- Indus Valley Cultural Elements In Minoan Crete By Bibhu Dev Misra

- "List of Indus Valley Civilization Sites in Haryana" | March 28, 2021

- THE INDUS CIVILIZATION

By A. H. Dani and B.K. Thapar

References[edit]

- ↑ Indus-Sarasvati Civilization By Sally Mallam

- ↑ P. 28 A Global History of Architecture By Francis D. K. Ching, Mark M. Jarzombek, Vikramaditya Prakash

- ↑ P. 23 South Asia in the World: An Introduction: An Introduction By Susan S Wadley

- ↑ "Indus era 8,000 years old, not 5,500; ended because of weaker monsoon" By Jhimli Mukherjee Pandey | TNN | May 29, 2016, 01.37 AM IST

- ↑ Sarkar, Anindya, Arati Deshpande Mukherjee, M. K. Bera, B. Das, Navin Juyal, P. Morthekai, R. D. Deshpande, V. S. Shinde, and L. S. Rao. “Oxygen Isotope in Archaeological Bioapatites from India: Implications to Climate Change and Decline of Bronze Age Harappan civilization.” Nature Scientific Reports 6 (May 2016): 1–9. doi:10.1038/srep26555.

- ↑ Possehl, Gregory L. Indus Age: The Beginnings. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999.

- ↑ Possehl, Gregory L. The Indus Civilization. Walnut Creek, CA: Alta Mira Press, 2002.

- ↑ K.N. Dikshit, “Origin of Early Harappan Cultures in the Sarasvati Valley: Recent Archaeological Evidence and Radiometric Dates,” Journal of Indian Ocean Archaeology 9 (2013): 132.

- ↑ Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark. Ancient Cities of the Indus Civilization. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- ↑ Lal, B. B. Piecing Together: Memoirs of an Archaeologist. New Delhi: Aryan International Books, 2011.

- ↑ Kautilya. The Arthaśāstra. Translated and edited by L. N. Rangarajan. New Delhi: Penguin Books, 1992.

- ↑ Jane R. McIntosh, A Peaceful Realm: The Rise and Fall of the Indus Civilization (Boulder: Westview Press, 2002), 53

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ “The Mahabharata and the Sindhu-Sarasvati Tradition”

By Subhash Kak

- ↑ "The Saraswati river is part of our rich cultural heritage and coordinated efforts are needed for its revival that would go a long way in making India Vishvaguru (world leader) once again. [The Indian Space Research Organization] has been working on Saraswati river for the last 20 years." ‒ Kavita Jain, Haryana Art and Cultural Affairs Minister, 2018[2]

- ↑ "Over the years, it can become a river of reasonable size," says octogenarian Darshan Lal Jain, an industrialist and president of the Saraswati Nadi Shodh Sansthan[3]

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Subcontinent from C. 7000 BCE to CE 1200 By Burjor Avari

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Archaeological Survey of India Publication:Indian Archaeology 1963-64 A Review

[4]

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ "Indus Valley Civilization". http://www.osmanian.com/2011/06/indus-valley-harappan-civilization.html.

- ↑ "Hidden agenda testing models of the social and political organisation of the Indus Valley tradition"

. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1899/2/1899_v2.pdf

.

- ↑ [5]

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263580655_Was_the_Rann_of_Kachchh_navigable_during_the_Harappan_times_Mid-Holocene_An_archaeological_perspective

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Gaur, A.S.. "Excavations at Kanjetar and Kaj on the Saurashtra Coast, Gujarat". http://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=AV2012095098.

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ India Archaeology 1976-77, A Review. Archaeological Survey of India.Page 19.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ "Nageswara: a Mature Harappan Shell Working Site on the Gulf of Kutch, Gujarat" (in en). https://www.harappa.com/content/nageswara-mature-harappan-shell-working-site-gulf-kutch-gujarat.

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315796119_Fish_Otoliths_from_Navinal_Kachchh_Gujarat_Identification_of_Taxa_and_Its_Implications

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ "What have been the most interesting findings about the Harappan Civilization during the last two decades?" (in en). https://www.harappa.com/answers/what-have-been-most-interesting-findings-about-harappan-civilization-during-last-two-decades.

- ↑ "Archaeological Survey of India". http://asi.nic.in/asi_exca_2007_sanauli.asp.

- ↑ Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Maharaja Sayyajirao University, Baroda. Excavations at Shikarpur, Gujarat 2008-2009."Archived copy"

. http://www.harappa.com/goladhoro/Shikarpur-2008-2009.pdf

.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ "An Ancient Harappan Genome Lacks Ancestry from Steppe Pastoralists or Iranian Farmers" By Vasant Shinde, Vagheesh Narasimhan, Nadin Rohland, Swapan Mallick, Matthew Mah, Mark Lipson, Nathan Nakatsuka, Nicole Adamski, Nasreen Broomandkoshbacht, Matthew Ferry, Ann Marie Lawson, Megan Michel, Jonas Oppenheimer, Kristin Stewardson, Nilesh Jadhav, Yong Jun Kim, Malvika Chaterjee, Avradeep Munshi, Amrithavalli Panyam, Pranjali Waghmare, Yogesh Yadav, Himani Patel, Amit Kaushik, Kumarasamy Thangaraj, Matthias Meyer, Nick Patterson, Niraj Rai,5, and David Reich (Published: Published online: September 5, 2019)

- ↑ "The Indian humped cattle Zebu, and elephant had been domesticated by the 7th to 6th millennium BCE."; P. 83 History of Ancient India Revisited, A Vedic-Puranic View. By Omesh K. Chopra

- ↑ All About: The Incredible Indus Valley By P. S. Quick

- ↑ P. 79 Calcutta Review By University of Calcutta

- ↑ P. 89 The Concept of Rudra-Śiva Through the Ages By Mahadev Chakravarti

- ↑ P. 461 The Cave Temples of India By James Burgess

- ↑ P. 21 The Presence of Siva By Stella Kramrisch

- ↑ P. 33 The Concept of Rudra-Śiva Through the Ages By Mahadev Chakravarti

- ↑ P. 104 The Birth of Kumāra By Kālidāsa

- ↑ P. 14 The Megha-Dūta of Kālidāsa By Kālidāsa

- ↑ P. 16 The Book of Hindu Imagery: Gods, Manifestations and Their Meaning By Eva Rudy Jansen

- The Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Swami Harshananda, Ram Krishna Math, Bangalore