Zoroastrianism and Hinduism

Inception of both the Religions[edit]

Both Zoroastrianism and Hinduism have similar origins, pay homage to the same spiritual seers, venerate the same gods and even have the same verses throughout the early scriptures. Mazdaen scholars Zubin Mehta and Gulshan Majeed[2] had noted a similarity of Kashmiri customs with Zoroastrian ones. In the modern era, some Mazdaen clerics had visited Kashmir, who include Azar Kaiwan[3] and his dozen disciples[4], and Mobad Zulfiqar Ardastani Sasani[5] who compiled the Dabistan-e Mazahib.

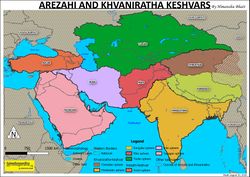

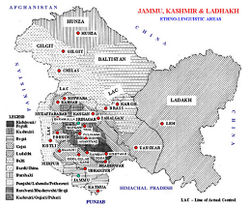

Zarathustra was definitely a Kashmiri Brahman from India as he was an Atharvan[6], who called himself a zaotar[7], manthran[8] and datta.[9] He was referred to as an erishi[10] and ratu[11].[12] He also wore the sacred thread and dressed like a traditional Kashmiri Pandit, compiled Gāthās containing Vedic verses, worshiped Varuna (Ahura Mazda) and venerated other holy Vedic Asuras. He lived as an ascetic in a cave[13] for some time and also had other traits similar to that of an Indian Brahman, not to mention other customs similar to those of Kashmiri Hindus. Further, the fact that Zarathustra personally debated Brahman clerics (i.e., Byas, Changragacha, Gautama) from India at King Vishtaspa’s court in Balkh shows how influential Indian spiritual preachers were then, and it only supports that Zarathustra himself was one. Also, linguistically, not only were some verses he wrote direct excerpts from the Vedas but the closest languages to his own, Avestan, are Sanskrit and Kashmiri. Both, the Vedic geography of Yama's domain and the Mazdaen geography of Yima's domain correspond to an area in central Kashmir. The geographical description of Zarathustra's birthplace in the Mazdaen scriptures match Kashmir's Diti (Daitya) and Indus (Veh) rivers and Urni Jabbar (Jabr) Mountain within Baramulla district. In addition, the descriptions of neighboring regions adjacent to Airyanem Vaeja, such as Ātaro-Pātakān, Kohistan, Kangdez and Panjistan match those of places surrounding Kashmir. Apart from these places in Mazdaen scriptures being in conformity with places in and around Kashmir, the birthplace of Tonpa Shenrab is also adjacent to Zarathustra's. (That makes sense because the religions of the 2 saints are similar in their concepts dualism, cimeration, and customs such as wearing of white turbans for sages.) Ancient scholars, such as Clement of Alexandria and Ammianus Marcellinus, connecting Zarathustra to Brahmans can definitely be seen, and even in modern times Godfrey Higgins had called him "Zerdusht the Brahmin[14]."

It is definitely not hard to imagine Brahmans in an Afghan king's court as there have been throughout history, and even during Zarathustra's time he converted at least 2 other Brahmans of the court, Changragach and Byas. Zarathustra also mentions having dealt with the Angras, and a Gautama.

Similarities[edit]

Zoroastrianism originated in India[edit]

Zarathustra's name[edit]

"Zarathustra became a generic name for 'great prophet' so several Zarathustras arose in the period 6000 to 600 BC the Avesta Y.XIX.18 named a hierarchy of five leaders, the supreme being called Zarathustrotema." - Duncan K. Malloch[15]

Just as the pseudonyms Gautama Buddha, Vardhman Mahavira, and Guru Nanak are reflective of the sages' names and titles, so too is the case of Zarathustra Spitama. 'Zarathustra' is a name that relates his devotion to Ahura Mazda.

| There are the master of the house, the lord of the borough, the lord of the town, the lord of the province, and the Zarathustra (the high-priest) as the fifth. | ||

—Avesta Yasna 19.18.50 [16] | ||

'Zarathustra' as a class of 'ustras' is alluded to in the Atharva Veda.

| Three are the names the ustra bears, Golden is one of them, he said. Glory and power, these are two. He with black tufts of hair shall strike. | ||

The ustras referred to in this passage are definitely humans because elsewhere too Atharvans with black hair (i.e., implying theur youth) are praised. In Mazdaen scriptures too, Athravans with black hair are praised.

| O Zarathushtra! let not that spell be shown to any one,

except by the father to his son, or by the brother to his brother from the same womb, or by the Athravan to his pupil in black hair, devoted to the good law, who, devoted to the good law, holy and brave, stills all the Drujes. |

||

There was "the Armenian Zoroaster, grandson of Zostrianus" ("Zostriani nepos"), who was the Pamphylian friend of Cyrus the Great. There was also a "Zoroaster" of Babylon whom Pythagoras had written of meeting. Further, the Changragach-Nameh and the Zarathusht-Nameh were written by Zarathusht Behrairi Pazdu, while Zaratusht Bahram was an important Mobed. Thus, this explains that the 'Zoroaster' written about after 6th century BCE wasn't always necessarily Zarathustra Spitama, and we can also cancel obscure regions as his supposed birthplace.

Zarathustra's surname 'Spitama' comes from his ancestor Spiti. This name traces its roots to the Spiti Valley of Himachal Pradesh, just south to Kashmir. This is also supported by the fact that Zarathustra had taken solitude at age 15 to Mt. Ushidaran which the Greater Bundahishn identifies as Mt. Kāf.[17] Today is a village in the Spiti Valley of Himachal Pradesh named Kāf.

'Spitama' itself has the Vedic Sanskrit attribute of containing 'tama', like the gotra patronyms of Gautama, Asvattama, Padmottama, Ratnottama, and Girghtama(s), as well as the titles of hiranya-vasi-mat-tama, rathi-tama, ratna-dha-tama, and sasvat-tama.

Background of erishis[edit]

According to the Rig Veda, Vasiśṭha Rṣi was the son of Mitra-Varuna by Urvashi. Vayu Purana[18] and Brahmanda Purana[19] mention that Shukra, Bhrgu, and Angirasa were born from the sacrificial fire of Brahma. The Jaiminiya Brahmana[20] and Satapatha Brahmana[21] mention that Bhrgu and Angirasa were born this way. Aitareya Brahmana [22] mentions this of Bṛhaspati, and Gopatha Brahmana[23] to that of Atharvan.

Athravans were Atharvans from India[edit]

Zarathustra was of the Athravan (Atharvan) priestly caste. The Avesta declares that Zarathustra was an Athravan.

|

Hail to us! for he is born, the Athravan Spitama Zarathustra. Zarathustra will offer us sacrifices with libations and bundles of baresma with libations and bundles of baresma and there will be the good Law of the worshipers of Mazda come and spread through all the seven Karshvares of the earth. |

||

—Avesta 24.94[25] | ||

The Atharvans are as ancient as the Rig Veda. It mentions that Brahmā taught the knowledge of Brahman to his eldest son Atharvan.[26] Further, the Atharvans are associated with fire symbolizing it to be as sacred to them as it was to the later Athravans. Bharadvaja says to Agni that Atharvan has churned Agni out from the lotus, from the head of everything.[27] Vitahavya also says that the Atharvans have brought Agni from the "dark-ones" (i.e., nights.)[28]

Angras are Angirasas[edit]

Further, Zarathustra in his Gāthās alludes to "old revelations"[29], and praises the Saoshyants[30] (fire-priests), and even exhorts his party of attendees to praise the Angras[31]. Hindu scriptures know the Angirasas (descendants of Rṣi Angiras) as the composers of the Atharva Veda, or as the "Atharvangirasa" and the Veda is also known as the Angiras Veda. (Angras are in no way connected to Angra Mainyu, the opposer of Ahura Mazda whose name means Dark Spirit.) Hence, those Angras mentioned by Zarathustra are also Vedic rṣis. He is referred to by some rṣis in the Rig Veda as their "father".[32] Angira is a son of Varuna, as are Bhargava and Vasiśṭha. Angirasas are sacerdotal families with ceremonial practices in the Atharva Veda.[33] Their connection to the sacred fire is such that the Rig Veda also names Agni as Angiras[34], and that the sons of Angiras were born of Agni[35]. In the RV, Angirasas were called "Sons of Heaven, Heroes of the Asura."[36]

The fact that Bhargavas are, like their subgroup Angirasas and the Athravans, also descendants of Vasiśṭha is established in Puranas.[37] Hence, Kava Uṣan (Shukra Acharya the Bhargava) is venerated and included as one of the holiest sages in Mazdayasna because he was also from Vahiśta (Vasiśṭha.)[38]

Sraosha of the Avesta is Bṛhasa (Bṛhaspati) of the Vedas who was the son of Angiras[39], so Sraosha is also of the category of Angras mentioned in the Avesta.

Zarathustra was of Vasiśṭha Gotra[edit]

The Denkard scripture specifically mentions that Zarathustra was a descendant of the law-giving immortals (Amesha Spentas, to which the Vahiśtas belong), as well as of "King Jam"[40] Mazdaen scriptures mention Vahiśta (Vasiśṭha) within the Avesta, wherein he is an Amesha Spenta[41] mentioned as Asha Vahiśta. In Mazdayasna, Asha Vahiśta is a divine lawgiver[42] and guardian of the Asha.[43] Vasiśṭha is a law-giver sage in many instances within the scriptures and is even quoted by other rṣis, such as Bhṛgu and Manu, when they prescribe societal laws.[44] Asha Vahiśta is also closely associated with the sacred fire in several Avestan passages[45][46], just as Vasiśṭha is. Vasiśṭha would have been a popular gotra in Kashmir especially because a major ashram of his was here, Vāngath[47].

The Atharvans are descended from Vasiśṭha Rṣi.[48] Vasiśṭha's dedication to Atharvan is demonstrated in the Rig Veda wherein after being filled with anger, he calms himself by reading the Atharva Mantra.[49] Vedic scholar Mallinatha writes in his commentary of the Kiratarjunya that the Śāstras declare that the mantras of Atharva Rṣi are preserved by Vaśiśṭha.[50] Just as there are several Vaśiśṭhas[51] within the community, the Avesta acknowledges that there are several Vahiśtas,[52] and refers to them as the "Lords of Asha." Even in the Vahistoistri Gāthā,[53] Francois De Blois notices that it consists of verses with a variable number of unstressed syllables.[54]

Avestan as a dialect of Sanskrit[edit]

"Slowly and gradually, it dawned upon them that the language of the Gatha and Zendavesta has very great kinship with the Sanskrta language; when the grammar of Panini, Katyayana, and Patanjali was applied then the Gāthās and Zendavesta came to be understood by the westerners. The lesson from this amazing fact is clear that once the Iranians of the Gatha and Zendavesta and the Indo-Aryans of the Vedas formed one single race, speaking language akin to Samskrta." - Yaqub Masih[55]

It is known that both Vedic Sanskrit and the Zhand Avestan languages were very close. In fact, some scholars have even stated that "the Parsi was derived from the language of the Brahmans"[56] like various Indian dialects. This view point was supported by "Zend language was at least a dialect of the Sanskrit."[57] Max Muller, William Jones[58] and Nathaniel Brassey Halhed[59] put forward this viewpoint.

Erskine Perry also was in the view that Avestan was a dialect of Sanskrit and was exported to ancient Persia from India but was never spoken there and his reasoning for this is that of the seven languages of ancient Persia mentioned in the Farhang-i-Jehangiri, none of them is referring Avestan language. Another scholar perpetuating the viewpoint of Avestan being a Sanskritic/Prakritic dialect was John Leyden.[60]

"Zend is a Brahmin language." - J.G. Cochrane[61]

- List of some Sanskrit and Avestan words

| Word | Sanskrit | Avestan |

|---|---|---|

| gold | hiranya | zaranya |

| army | séna | haena |

| spear | rsti | arsti |

| sovereignty | ksatra | khshathra |

| lord | ásura | ahura |

| sacrifice | yajñá | yasna |

| sacrificing priest | hótar | zaotar |

| worship | stotra | zaothra |

| sacrificing drink | sóma | haoma |

| member of

religious community |

aryamán | airyaman |

| god | deva | deva |

| demon | rákshas | rakhshas[62] |

| cosmic order | rta | arstat/arta |

- List of some Sanskrit and Avestan names for gods

| Sanskrit | Avestan | Status within Mazdayasna | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apām Napāt | Apam Napat | Yazata | Son of water, a god |

| Aramati | Armaiti | Amesha Spenta | Archangel of immortality |

| Baga | Bagha | Yazata | A sun god |

| Ila | Iza | Yazata | Goddess of sacrifice |

| Manu | Manu(shchihr) | Ancestor | Son of Vivanhvant |

| Marut | Marut | Yazata | Cloud god |

| Mitra | Mithra | Yazata | A sun god |

| Nābhānedista | Nabanazdishta | Ancestor | Name of Manu |

| Narasansa | Nairyosangha | Yazata | A fire god |

| Surya | Hvara | Yazata | A sun god |

| Trita | Thrita | Yazata | God of healing |

| Twastra | Thworesta | Yazata | Artificer of the gods |

| Usha | Ushah | Yazata | The Goddess Dawn |

| Varuna | Varuna | Ahura Mazda (one of his 101 names[63]) | The Wise Lord, creator of all |

| Vayu | Vayu | Yazata | A wind god |

| Vivasvant | Vivanhvant | Yazata | A sun god |

| Vritrahan | Verethragna | Yazata | Slayer of Verethra |

| Vasiśṭha | Vahiśta | Amesha Spenta | Archangel and lawgiver to humanity |

| Yama | Yima | King | A pious king of Airyanem Vaeja |

Apart from the gods that are common to both Zoroastrianism and Hinduism, names of some other Hindu gods are carried by even modern day Persian speakers. For example, the names 'Śiva' (Charming) and variations of 'Rāma' (Black)[64] are used by Iranic speakers, such as Persians and Pashtuns. King Ram is also added in names such as 'Shahram' (King Rām) and 'Vahram'/Bahram' (Virtuous Rām), which was the other name of Verethragna mentioned in the Bahram Yasht of the Avesta. The Sassanian kings took the Vahram title, such "Vahram I" (ab. AD 273-276.)[65] Toponyms as well include 'Ram'/'Raman' in their syntax, such as Ramsar in Iran.

- Daēvā does not mean Deva

"The term daeva as synonym with raksasa and distinct from deva survives in Kashmir." - Ashvini Agrawal[66]

Whereas the root of the Avestan word 'daēvā' is "daē" meaning god, of 'deva' it is "div", which means light. Zarathustra wrote in his Gāthās, "daēnāe paouruyae dae ahura!"[67] Hence, the word for religion in Avestan is daēnā.[68]

That deva carries positive connotations is seen in Gāthā 17.4 Yasna 53.4 wherein Ahura Mazda is said to be a "devaav ahuraaha."

As Airyanem Vaeja is in Kashmiri, the Avestan and Kashmiri vocabulary are similar. 'Dai' is still used by Kashmiris to refer as god.[1][2][3]

Many Avestan verses are from Vedas[edit]

The Rig Veda is believed to have been the oldest scripture in the world. In it are verses that are identical to ones within the Zhand Avesta, except the dialect of the Avesta is in Avestan. Ahura Mazda, whom the Mazdaens worship as the Supreme Lord is the Avestan equivalent to Vedic Sanskrit's Asura Medhira or Asura Mada. These terms mean "Wise Lord" and in the Rig Veda this phrase appears in a few places, in one verse being "kṣayannasmabhyamasura".

| With bending down, oblations, sacrifices, O Varuna, we deprecate thine anger:

Wise Asura, thou King of wide dominion, loosen the bonds of sins by us committed.[69] |

||

—Rig Veda 24.14 | ||

There are several passages in the Vedas (especially the Atharva Veda) and Avesta that are identical, with the only difference that they are in the different dialects, Avestan and Vedic Sanskrit.

There are two sets of Mazdaen scriptures; the Zhand Avesta[70] and the Khorda-Avesta.[71] The Zhand contains 3 further sets of writings, known as the Gāthās[72] compiled by Zarathustra, and the Vendidad, and Vispered. (Not surprisingly, Hindu scriptures also have collections known as Gāthas, such as the Vasant Gātha and Theragātha.) The Khorda contains short prayers known as Yashts. They are written in a metre much like the Vedas. Normally they contain 15 syllables known in Sanskrit as Gayatri asuri) like hymns of the Rig Veda, or Ushnih asuri such as in the Gāthā Vohu Khshathrem[73] or of 11 syllables in the Pankti asuri form, such as in the Ustavaiti Gātha.

Some scholars also note that there is a connection between Bhargava Rṣi and Zoroastrianism, as the Atharva Veda portion composed by him is known as Bhargava Upastha and the latter word is the Sanskrit version of the term 'Avesta'.[74]

"The Avesta is nearer the Veda than the Veda to its own epic Sanskrit." - Dr. L. H. Mills

- Some identical verses from Vedas and the Avesta

| Scripture | Sanskrit | Avestan | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rig Veda (10.87.21) / Zhand Avesta (Gāthā 17.4 Yasna 53.4) |

mahaantaa mitraa varunaa samraajaa devaav asuraaha sakhe

sakhaayaam ajaro jarimne agne martyaan amartyas tvam nah |

mahaantaa mitraa varunaa devaav ahuraaha sakhe ya fedroi vidaat

patyaye caa vaastrevyo at caa khatratave ashaauno ashavavyo |

O Ahura Mazda, you appear as the father, the ruler, the friend, the worker and as knowledge.

It is your immense mercy that has given a mortal the fortune to stay at your feet. |

| Atharva Veda 7.66 / Zhand Avesta (Prishni, Chapter 8, Gāthā 12) |

yadi antareekshe yadi vaate aasa yadi vriksheshu yadi bolapashu

yad ashravan pashava ud-yamaanam tad braahmanam punar asmaan upaitu |

yadi antareekshe yadi vaate aasa yadi vriksheshu yadi bolapashu

yad ashravan pashava ud-yamaanam tad braahmanam punar asmaan upaitu |

O Lord! Whether you be in the sky or in the wind, in the forest or in the waves.

No matter where you are, come to us once. All living beings restlessly await the sound of your footsteps. |

| Rig Veda / Zhand Avesta (Gāthā 17.4, Yasna 29) |

majadaah sakritva smarishthah | madaatta sakhaare marharinto | Only that supreme being is worthy of worship. |

| Atharva Veda / Zhand Avesta (Yasna 31.8) | vishva duraksho jinavati | vispa drakshu janaiti | All (every) evil spirit is slain. |

| Atharva Veda / Zhand Avesta | vishva duraksho nashyati | vispa drakshu naashaiti | All (every) evil spirit goes away. |

| Atharva Veda / Zhand Avesta | yadaa shrinoti etaam vaacaam | yathaa hanoti aisham vaacam | When he hears these words. |

Why Zarathustra's teachings are called Zhand Avesta[edit]

The Avesta is also known as the Zhand Avesta. Zhand is the Avestan equivalent of 'Chhand'.

| O Kshatriya, the verses that were recited by Atharvan to a conclave of great sages, in days of old, are known by the name of Chhandas. They are not be regarded as acquainted with the Chhandas who have only read through the Vedas, without having attained to the knowledge of Him who is known through the Vedas. The Chhandas, O best of men, become the means of obtaining Brahm (Moksha) independently and without the necessity of anything foreign. | ||

—Mahabharata Udyoga Parva Chapter 43:4[75] | ||

The word 'Avesta' comes from Sanskrit 'Abhyasta', which means Repeated. Hence, the Avesta (Abhyasta) is basically a repetition of Zarathustra's teachings.

Zarathustra was born in Kashmir[edit]

The birthplace of Zarathustra has been a subject of dispute ever since the Greek, Latin and later the Muslim writers came to know of him and his teachings. Cephalion, Eusebius, and Justin believed it was either in Balkh (Greek: Bactria) or the eastern Iranian Plateau, while Pliny and Origen thought Media or the western Iranian Plateau, and Muslim authors like Shahrastani and al-Tuabari believed it was western Iran. [76] While Zarathustra's place of birth has been postulated in various places even in modern times, including within areas not historically included by authors, such as in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, a few scholars have believed that he was born in Kashmir. Shrikant G. Talageri[77] and T. Lloyd Stanley[78] were proponents of this Kashmiri Airyanem Vaeja viewpoint. Mazdaen scriptures[79] mention repeatedly that Zarathustra was born in Airyanem Vaeja, also known as Airyanam Dakhyunam. However, Zarathustra moved from there to Balkh, where he was given sanctuary by its king and he had become a royal sage. The Mazdaen scriptures further say that many other people of Airyanem Vaeja had moved out with the dramatic climate change whereby snow and cold weather became much more frequent. Zarathustra was regarded as a pious Godman for the Balkhan administrators of his time and India was recognized as a center of spiritual and scientific wisdom. This is why Mazdaean scriptures show that King Vishtaspa's court was already familiar with the Indian Brahman adviser Changragach who was teacher to minister Jamaspa, even before Zarathustra's arrival to Balkh. The Brahman Byas was also welcome in King Vishtaspa's court and met and had become a disciple of Zarathustra. King Vishtaspa (Greek: Hystaspes) was the father of King Darius I of the Balkh Kingdom and he had studied astronomy amongst the Brahmans of India.[80]

There are similarities noticed by scholars such as Subhash Kak and Zubin Mehta which are described by them between Mazdaen practices of Kashmiri Hindus. These include the sacred thread for women (called aetapan in Kashmiri) and the sacred shirt (sadr.) The festival of Nuvruz[81] in commemoration of King Yima is known as Navreh in Kashmir which is celebrated by Kashmiri Hindus. Furthermore, the folklore of Kashmir too has many tales where devas[82] are antagonists to both devas and asuras. As the title Zarathustra has many variations, such as 'Zartust' and 'Zardost', the Sanskrit equivalent of his title is 'Haritustra Svitma'. The 'p' in 'Spitama' corresponds to a 'v' in Sanskrit just as Avestan 'Pourusarpa' is 'Purusarva' is Sanskrit. Whereas the consonant 's' of many Sanskrit words becomes 'h' in Avestan, 'Svitama' maintains its letter because it is followed by a 'v', just as how the 's' in Sanskrit 'asva' (horse) becomes 'aspa' (i.e., 'Dhruwaspa' means She who possesses strong horses, and animals within names were more common, such as Yuvanasva and Vindhyasva.) As 'Spitama' means white, the Sanskrit word for the color-based name is 'Svitama'. Svita is a metaphorical characteristic associated with purity and normally associated with Brahmans in the Vedas. For example, the Rig Veda[83] describes the Vasiśṭha ṛṣis as 'svityam' (white), 'svityanco' (dressed in white)[84] and white-robed. Zarathustra dresses in white as well Mazdaen priests also dress up in white. The connection between Vasiśṭha ṛṣi with Atharvan Rṣi is a very close one.

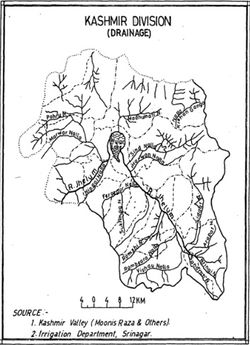

Identification of Avestan sacred places in Kashmir[edit]

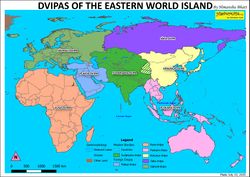

- See also: King Yama's Kingdom was in Kashmir, Rig Vedic rivers, India is the homeland of Indo-Europeans

Kashmir itself has taken on various endonyms and exonymns, which can make pinpointing whether an author is talking about the region. In this case, the Mazdaen scriptures refer to it as Airyanem Vaeja and Anu-Varshte. In addition to these, the region has been called Kashmar, Kashir, Kashrat, Kasherumana, Khache-yul, Kasperia, and Kipin, Vitastika, and it together with Balawaristan is known as Hari-varṣa, Naishadha-varṣa, Uttara-Patha, and Deva-Kuru. It has symbolic and historic association with rṣis, and has been known as Rishivaer/Rishi-wara (Land of Rṣis.) Even Persian literature has mentioned the words Reshi, Reshout, and Rea-Shivat when speaking about Kashmir.[85] Firdaus (Paradise) is another Persian word that has been used to describe Kashmir. The word Airyanem within the phrase Airyanem Vaeja means Of the Aryans. Jain mantras use the term in the salutations, such as "Namo Airiyanam" in the Namokar Mantra, and "Om Hreem Namo Airiyanam" as an astrological mantra for Jupiter.

- Why Airyanem Vaeja is also called Anu-Varshte

The Avesta mentions 'Anu-varshte daēnāyai'[86], meaning "religion of Anu-land." This prayer requests the help of Aredvi Sura to help Zarathustra able to convince King Vishtaspa to accept the 'religion of Anu-Varshte.' The Anu tribe, also known as Anavas in many Hindu scriptures, were based in Kashmir. There's even a village called Ainu Brai after them within Pahalgam tehsil of Anantanag in Kashmir. That they later annexed nearby lands, including Balkh in Afghanistan, is evident from scriptures such as that of Panani's that tells us of Anava settlements.

In the Anava lineage, 7th in descent from Anu were brothers Usinara and Titikshu. The territories gained by the Anavas was split by these brothers wherein Usinara had grasped Kashmir and the Punjab[87] while Titikshu gained rulership over eastern territories of Anga (Bihar), Vanga (Bengal), Suhma, Pundra, and Kalinga (Orissa.)

Because Kashmir has prehistorically been the Anava stronghold, even during the Dasarajna War as the Rig Veda mentions, it is acknowledged as such both in Hindu scriptures (i.e., Atharva Veda[88]) and in the Mazdaen Avesta.

One of the reasons why historically Balkh and some other regions of modern Afghanistan were Indianized (and hence, referred to as Ariana) is because the Anavas also held areas of Afghanistan under their suzerainty. In Vrtlikara[89], Sage Panini (from Afghanistan himself) mentions that there are 2 Anava settlements of the Usinara called Ahvajala and Saudarsana. Even scholarly Chinese visitors to ancient India, Fa Hien and Yuan Chwang describe the story of a certain King Usinara told at Udyana (modern Swat Valley where people are mostly ethnically Afghans) that sacrificed his life to save that of a dove's.

To little surprise the Kurma Purana[90] mentions Anava being 1 of the 7 sons (Saprtarṣis) of Vasiśṭha, meaning that Vasiśṭha had married within the royal family. Within the same Manavatara era another son of Vasiśṭha was Shukra or Kavi Uṣana (Kava Uṣan of Mazdaen scriptures), meaning that Vasiśṭha had likely married multiple women.

- Jabr Mountain is Urni Jabbar Mountain

Zarathustra was said to have been born in the village of Raji[91] by the Dareja[92] River near the Jabr Mountain[93]. In Vendidad 1.16 where the city of Ragha is referred to the Pahlevi commentators add that it is in Ātaro-Pātakān. In Kashmir, there is a village of similar name, Renji in Sopore district[94]. There are other villages and towns bearing 'Rai' in their names. These are Raipura, Raika Gura, Raika Labanah, Raika Mahuva, Rainawari, and Rai'than. Kashmir bears the villages Raj Pora Thandakasi[95] Dareja is also mentioned to be where Zarathustra's father lived[96], hence, Zarathustra lived there too. Today in Kashmir there are the 2 rivers Darga Burzil and Darga Rattu that merge to form the larger Astore River.[97]

- Amui (Amar) is Amartnath in Kashmir

| The sorcerer (Zandak), who is full of death, founded a city of Amui (Amar), and Zardusht, descendant of Spitama, was of that place. | ||

—Satroiha-i Airan 59 | ||

This verse is saying that Zarathustra was of this place, meaning he likely spent a significant portion of his life there. This is also the opinion Carl Bezold and Louis Herbert Gray.

Amarnath pilgrimage is Anantanag district, bordering Baramulla district, where Zarathustra was born.

- Rai is Raihan Bag in Kashmir

| Zarathustra was of that place (Rai.) | ||

—Vendidad[98] | ||

This village is very close to the Urni Jabbar mountain, it is in Khag tehsil in the Badgam district.

- Daitya River is the Jhelum

Scriptures mention the original homeland of the religion and of Zarathustra, but due to placename changes, the exact location has been hard to pinpoint. Daityas are also mentioned (as are Danavas) in ancient Mazdaen texts as good beings. It is believed that the homeland of the Aryans is located by the Daitya River[100] as said in this Avesta quote, "Airyanem Vaejo vanghuydo daityayo", which Darmesteter translates as "the Airyana Vaejo, by the good (vanghuhi) river Daitya."[101] In later scriptures, the river is known as 'Veh Daiti' wherein the Veh refers to the Daiti being its tributary. Veh in the Bundahishn is mentioned as the Indus River. Bundahishn mentions that Veh is also called Mehra by Indians, and surely enough Mehra is a town along the Indus. Veyhind (Udabhānḍapur, modern Hund) is also a town reflecting Indus' Veh-name. Further, Vahika was the name of a kingdom around the Indus and its meaning is Land of the River.[102] (Here was Arattadesa or Panchanada.) Kashmir has a river named Diti which is said to have been an incarnation of Diti, mother of the Daityas.[103] The connection between the Diti River of Mazdaen scriptures and the patriarch Diti of Hindu scriptures has been observed by James Hewitt.[104] Daityas have been mentioned in Hindu Epics as staunch Asuras. This river is also popularly called as Chandravati, Arapath or Harshapatha.[105] The Arapath Valley begins where the Arapath (Diti) stream stems out of Jhelum.[106] Because the Diti becomes the Jhelum at their stem, the Mazdaen scriptures just call the entire Jhelum as Daitya River. They also refer to it as the Veh Daiti because the Jhelum itself merges into the Indus, which the Bundahishn calls 'Veh'. (The entire Jhelum is certainly known by many names in India.[107].) Just as the Bundahishn calls the Daitya "the chief of all streams"[108], scholars note the Jhelum has more streams than any other Indus tributary. Even the Nilamata Purana declares that Varuna "knows the man who merely bathes in the Vitasta."[109]

Zarathustra used to bathe in the Dareja affluent of the Daitya. In the same way, Hindus are encouraged to bathe in it among rivers of Kashmir.

| After that on the 14th of the dark-half of the month, one should take bath, before sun-rise, in the cool water of the Vitasta or the Visoka or the Candravati (modern Diti) or the Harsapatha or the Trikoti or the Sindhu or the holy Kanakavahini or any other holy river or the water-reservoirs and the lakes. | ||

King Vishtaspa used to perform sacrifices along the Dareja. In the same way, Hindus are encouraged to perform execute the Rajasuya ceremony along the Diti.

| By bathing in Harsapatha, one is honoured in the world of Sakra and by bathing in Candravati (modern Diti) one gets the merit of (giving) ten cows.

Holy is the river Harsapatha and so also is Candravati (modern Diti). The wise say that there accrues (the merit of the performance of) Rajasuya at the confluence of these two. |

||

- Dareja is an affluent of Daitya River

The Dareja is the lower Jhelum from which stretches from Hairbal Ki Galli to Muzaffarabad to join the other part of the Jhelum that stretches Mangla Reservoir to Muzaffarabad. Today this stream is known as the Lower Jhelum.

| For the occurrence of the seventh questioning, which is Amurdad's, the spirits of plants have come out with Zaratust to a conference on the river Dareja's high ground on the bank of the waters of the Daiti. | ||

—Zadsparam 22.5.12[110] | ||

| Of those eighteen principal rivers, distinct from the Arag river (Amu Darya) and Vêh river (Indus), and the other rivers which flow out from them, I will mention the more famous: the Arag river, the Vêh river, the Diglat river (Yarkhun) they call also again the Vêh river, the Frât river, the Dâîtîk river (Jhelum), the Dargâm river, the Zôndak river, the Harôî river, the Marv river, the Hêtûmand river (Helmand), the Akhôshir river, the Nâvadâ river, the Zîsmand river, the Khvegand river, the Balkh river (Balkhab), the Mehrvâ river they call the Hendvâ river (Indus), the Spêd river, the Rad river which they call also the Koir, the Khvaraê river which they call also the Mesrgân, the Harhaz river, the Teremet river, the Khvanaîdis river, the Dâraga (Jhelum's stream Lower Jhelum) river, the Kâsîk river, the Sêd ('shining') river Pêdâ-meyan or Katru-meyan river of Mokarstân. | ||

- Bundahishn's Kohistan is Kohistan of Karakoram Range

| The Daitik river (Datya) rises in Airan-vej and flows through Kohistan. | ||

—Bundahishn 20.13 | ||

Kohistan is also referred in the Pazhand transcription of the Bundahishn as Gurjistan.[112] The Gurjistan that is referred to is the Gurez Valley in Kashmir. Gurez is acknowledged by V. R. Raghavan as to have come from 'Gurj' and 'Gurjur'.[113]

Gopat, also known as Gopistan is another name for Kohistan.

| The land of Gopat has a common border with Eran Vez on the banks of the river Datya. | ||

—Bundahishn 11.A.7[114] | ||

Subdastan is also a toponym of Kohistan.

| The river Datya comes from Eran Vez and goes to Subdastan. | ||

—Bundahishn | ||

- Bundahishn's Panjistan is Panjistan of Punjab

Panjistan is mentioned as possessing the Zend River. The name in present-day is used to refer to a region of northeastern Punjab region. Even the language spoken there is called Panjistani.

The Pahlavi word 'Zend' (referring to a city, not the Zhand Avesta) is the translation of local 'Jand' within the Punjab. There are cities and towns throughout the region named Jand. Hence, the river is called Jand (Zend.)

| The Zend River passes through the mountains of Panjistan, and flows away to the Haro River. | ||

—Bundahishn 20.15 | ||

- Hara Mountains are Himalayas and the river Aravand is Sarasvati

Aravand, being Sarasvati, originates in Uttarakhand. Mountains across the northwestern Himalayas contain 'Hara' within their names, such as Haramukh Mountain[115] and Haramosh Mountain nearby in Gilgitstan. Hara is the shortened form of the mountain range's name Hara-Berezaiti.

Hara's most sacred peaks are known as Us-Hindava (Pahlevi: Usindam) and the Hukairya (Pahlevi: Hugar.) In the Avesta, Us-Hindava Mountain (which means Upper Indian Mountain) is also spoken of as Usindam and Usinda Mountain and it receives water from a "golden channel" from Mt. Hukairya (Of good deeds[116].)

Further, the Aredvi Sura River that the Avesta writes about, is the Sarasvati River of the Rig Veda is said to flow from Hara into the Vourukasha Sea[117] (Indian Ocean.) Sarasvati flowed from Hardikun Glacier (West Harhwal Bandarpanch Masif) and took its coarse into the Indian Ocean. To further, that Avestan Aravand was in Uttarakhand is that it mentions god Sraoesa (Avestan name of Bṛhaspati) living in the Hukairya mountains. There is a praśasti dedicated to Sarasvati inscribed in Madhya Pradesh, which states that Sarasvati lived in heaven together with Bṛhaspati.[118]

Also, the Avesta speaks of the Aravand River, which is another name for Aredvi Sura, and it is the Avestan translated name of Amaravati River, Sarasvati's other name.

- Mount Kāf is Mount Meru

Mt. Kāf is the same mountain that Zarathustra is believed in legends to have gone into recluse. In Mazdaen sources it is usually called Ushidarena. In Hindu sources a Kashmiri mountain called Ushiraka (also referred to as 'Darva' and 'Abhisara') is mentioned as a place where people are sent for solitude. It is also mentioned in Buddhist texts as Ushiraddhaja and Ushira-giri, and as Ushinara-giri in the Kathasaritsagara.

Al-Biruni mentioned that this is the same mountain that Indians call Lokaloka.[119]

The modern K2 mountain is Mt. Meru. It is in the boundary between the Karakoram and the Himalayas. The Karakoram (Black Mountains) are also known as Krishnagiri (Black Mountains) in Sanskrit. As a lot of places around Kashmir and Balawaristan contain 'giri' or 'gir' within their names.

Scholars like Charles Hamilton Smith and Samuel Kneeland had identified that the Kāf mountain or mountains are just north of the Indus River.[120] The K2 is just north of Indus River.

- Mount Cinvat is Mount Cṛṅgvāt

A mountain mentioned in Mazdaen scriptures is Cinvat. In Hindu texts there is a mountain associated with Meru because the latter's waters flow through the Cṛṅgvāt (also known as Tri-Cṛṅga.)

The meaning of the Sanskrit word 'Cṛṅgvāt' is summit peak, and 'Cṛṅgi' is used in general for the placenames of peaks of the Himalayas[121] and of Sringaverapura (modern Allahabad), Srisringa, Chirtasringa, and Hiranyasringa.

- Outer versus Inner Kashmir

The Bundahishn divides Kashmir into 3; inner, central, and outer. Inner it calls "Kashmir-e andaron." Other scholars, such as Al-Idrisi, Dimashqi, Ibn Khaldun[122], and Shariyar b. Burzurg, have noted this distinction as well when writing of the region. Geographer Al-Mas'udi wrote that Inner Kashmir was founded by Kai Kaus. Historically in India, Kashmir has been written of as 3; Kamraz (Kramarajya or Kamraj), Yamraz (Yamrajya or Yamraj), and Maraz (Madvarajya or Maraj.)

| Included in the latter are other regions, such as Kangdez, the country of Saokavastan, the desert of the Arabs, the desert of Peshanse, the river of Navtagh, Eran-vej, the var made by Yima and Inner Kashmir. | ||

—Bundahishn | ||

This passage distinguishes Airyanem Vaeja (Eran-vej) from Yima's var and Inner Kashmir. That then leaves the question: If this Bundahishn verse covers all lands from the Arabian Peninsula to Inner Kashmir, then where is 'Outer Kashmir'? Historically the Kashmir Valley had been divided into 3 regions; Kamraj (ruled by Kamran), Yamraj (ruled by Yama or Yima), and Maraj (ruled by Maran.) Because the passage mentions Eran-vej, the Yama's var, and Inner Kashmir in that consecutive order it aligns with the sequence of Outer Kashmir or Kamraj, Central Kashmir or Yima's vat, and Maraj or Inner Kashmir. Further, Kamraj includes Baramulla district which contains the Veh, Daitya, and Dareja rivers as well as Mt. Jabr. Hence, the Bundahishn's author of the excerpt purposely mentioned these regions in that order.

Kashmir lies on a plateau surrounded by high inaccessible mountains. The south and east of the country belong to the Hindus (Indians), the west to various kings, the Bolar-Shah and the Shugnan-Shah, and the more remote parts up to the frontiers of Badakhshan to the Wakhan-Shah. The north and a part of the east belong to the Turks of the Khota and Tibet. - Al-Biruni[123]

- More identifiers of Kashmir

"If India were the original home of Indo-Europeans, it must also be the birth place of Zarathushtra. If the Zoroastrians had migrated out of India, they would have carried memories of the geography they left behind. Avestan literature is not familiar with the Indus. In fact, it believes Indus and Oxus to be the same. In contrast, Avesta itself refers to the features in Afghanistan." - Rajesh Kochhar[124]

Rajesh Kochhar's statement that Zarathustra would have had to have been born in India for it to have been the Indo-European homeland holds true, because the Avesta indeed mentions toponyms of features in northern India, mainly from Kashmir. The reason why most places in the Avesta are of Afghanistan is because Zarathustra, who was not from the Balkh Kingdom and had migrated there as most scholars agree, had only composed the Gāthās of the Avesta, whereas the rest of it was composed by his converts in Balkh. It is believed that the time gap between the Gāthās and the rest of the Avesta are centuries.[125] Scholars believe that this can be seen from "the poor grammatical condition of the language" of the Vendidad portion of the Avesta.[126] Kochhar also says Mazdaens who migrated would have to carry the memories of India with them, because the first Mazdaens were Zarathustra's family including his cousin Maidhyomaongha, also known as Maidhyoimah or Medhyomah, brother-in-laws Frashaoshtra and Jamaspa,[127] wife Hvovi, his daughters named Freni, Thriti and Pourushista, and his three sons which migrated with him, Zarathustra was the only compiler of the Avesta out of them. Apart from Zarathustra and his family, the first community of adherents was founded by King Vishtaspa[128] Interestingly enough, the king converts[129] after recognizing Zarathustra's holyness, when the prophet healed his paralyzed horse[130] just like the Sant Kabir and Sant Namdev [131] brought back a cow to life to earn the faith of kings. So because Kochhar asserts that India must be the Indo-European homeland by meeting his criteria, then India is Airyanem Vaeja.

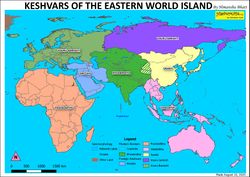

India in general is overlooked by modern scholars who study the Mazdaen scriptures. Of importance is Mithra, who is associated with the Indian Subcontinent. His dominion is geographically described in the Mihir-Yasht as extending from eastern India and the Hapta Hindava to western India and from the Steppes of the north to the Indian Ocean. The Avesta mentions Four Waters, which are four rivers of paradise. Kashmiri poets have written of "four rivers of paradise" in their works. The Four Waters of paradise according to the Avesta are:[132]

- The Azi

- The Agenayo

- The Dregudaya

- The Mataras

The water of these has a trait that they contain honey or honey-sweet water: "Two crossing canals that joined in a pond and which symbolized the four rivers of Paradise where milk, honey, wine and water flow."[133] This same bed of four rivers is the one referred to in the Rig Veda. The Veda mentions waters filled with honey-sweet water as the greatest work of nature: "The noblest, the most wonderful work of this magnificent one (Indra) is that of having filled the bed of the four rivers with water as sweet as honey."[134] The river of Kashmir which has four streams is the Jhelum and its four branches are Arapath (the Diti River), Vishau, Rimiyara and Lidar.[135] As Airyanem Vaeja is said to have been the birthplace of the first set of humans, the Kashmiris too state the human origin story about Kashmir.

"Aryana Vaeja has been placed in Media by inhabitants of Persia and Media. But this is only a transfer...which has nothing primitive and has only originated in consequence of the real site being forgotten."[136]

Zoroastrianism's scholars have written about the origins of the Mazdaens from India. Max Muller had said that, "The Zoroastrians were a colony from northern India."[137] M. Michel Break wrote, "The Zoroastrians were a colony from Northern India."[138]

Also identified in the Mazdaen scriptures are people such as Yima (Yama) and Manushchihr (Manu),[139] who have traditionally been strongly associated with Kashmir. Manushchihr in the Avestan Yasht[140] is mentioned as "the holy Manushchihr, the son of Airyu."

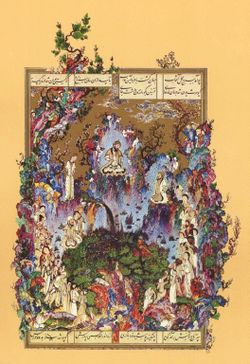

| Zardasht is said to have planted, under auspicious circumstances, two cypress-tress, one in Kashmir and the other in Farumad-tus, and the Majusi (Magi) believe that he brought the cypress from paradise when he planted it in those places. | ||

—Farhang-i-Jehangiri | ||

Both the Farhang-i-Jehangiri and the Shahnameh mention that Zarathustra had planted a cypress tree at a place named Kashmar. This place in the prior text is named also as Kashmir. The composers of the Rehbar-i-Din-i-Zarthoshti (Dastur Erachjee Sorabjee Meherji Rana) and Dabistan (Mohsan Fani), believed this to be the Kashmir in India. Though the Kashmar/Kashmir in the story is actually a town in Khorasan, one can see that the etymological derivation of 'Kashmar' is from the more ancient region of Indian Kashmir. It's quite possible that the seeds to grow the tree came from Kashmir. Certainly, cypress tress exist in Kashmir, and the local species is known as Cupressus cashmeriana.

- Zarathustra learning from and preaching to other Vedic scholars

Ancient Greek scholars, such as Clement of Alexandria and Ammianus Marcellinus[141], had written that Zoroaster had studied with the Brahmans of India. We know from Mazdaen literature that in his youth, Zarathustra's preceptor's name is Burzin Kuru(s), and the Kurus were a dynasty that had then dominated in parts of North India and in Afghanistan. Kashmir of course, is historically known as a part of Deva-Kuru. Further, even today there is the Burzahom Neolithic site next to Baramulla district in Kashmir, and the Draga Burzil stream in Kashmir, only further showing that the name Burzin has a connection to Kashmir. Ammianus had written that the Magi derived some of their most secret doctrines from the "Indian Brachmans" (i.e., Brahmans.)[142] Arabian writers have given a lot of information concerning the learning which Zoroaster acquired from the Indian Brahmans.[143] Ammianus also states in his 23rd Book of History that Prince Gushtasp (King Vishtasta's brother) went deep into the secluded areas of northern India and having reached a forest for retreat of the most exalted Brahmans, he learned spiritual knowledge from the Brahmans there and then returned back to his domain to preach this newly acquired wisdom to the Magi.[144] Par Thomas Maurice believed and wrote that Zarathustra had studied with Brahmans in India.[145] Kashmiri Brahmans are known synonymously as Kashmiri Pandits or simply as 'Pandits' (Scholars) and Anquetil du Perron believes that the Mazdaen scripture the Dhup Nihang mentions Mazdaen Pandits. The 8th century CE scripture refers to three Dasturs called 'Pandits' whose names were Bio Pandit, Djsul Pandit and Schobul Pandit.[146] Their names appear in the prayers of that scripture.[147] Interestingly enough, the word 'Dastur' is used in Kashmiri to mean custom.[148] Furthermore, Ibn al-Athir too and written that Zarathustra had been in India at one point.[149]

According to the Canda's Persian text, the Changragach Nameh, an Indian Brahman was called to King Gushtasp's palace to discuss with Zarathustra the Mazdaen religion. The Brahman after his discussion had became a preacher of the religion and went back to India where he established followers and temples.[150] Changragacha's name bares similarity to a placename, 'Chandrabhāga'. Another known Brahman that was a disciple of Zarathustra was a sage from India named Byas (in the lineage of Vyas)[151], and likely Nāidyāongha Gautama (a sage in the lineage of Nodhasa Gautama.) According to the Bhaviṣya Purāṇa, the Magi had first settled on the Chandrabhāga.[152] This account also coincides with Timur's finding "fire-worshipers" in Punjab. Further, Aristoboulos, when visiting Taxila,[153] had stated that the dead were "thrown out to be devoured by vultures."[154] This practice is still observed in parts of western Tibet.[155] Even Buddhist scriptures mention the great charnal fields near Simhapura in Kashmir wherein corpses were fed to wild animals for disposal.[156] Further, within Taxila had existed a great Jandial fire temple mentioned by Philostratus.[157] In the 1079 CE century, Sultan Ibrahim the Ghaznavid had attacked a community of Mazdaens at Dehra (probably Dehra Dun.) Then from Timur's invasion of India, among his captives of both Mazdaens and Hindus from Tughlikpur, some were Mazdaens who offered fierce resistance. In 1504 CE, Bedauni mentioned that Sultan Sikander destroyed fire-altars.[158]

- Relationship between the Magi and Indian Hindu Priests

The Magi being Athravans were accepted as Brahmans and they settled in Punjab first when they were brought by Samba (son of Kṛṣṇa) and they spread from there to other parts of the Indian Subcontinent including Karnataka and Nepal which are also known as the Magacharya or Maga Brahman today.

- Where nations speak Avestan-like languages today

As Zarathustra had spoken Avestan, the language likely would have been spoken in a place where it was popular. Today, Kashmiri[159][160][161] (Koshuri) is closest language to Sanskrit and hence to Avestan that is spoken by a linguistic group very similar to Rig Vedic Sanskrit. In addition, languages very close to Sanskrit which are also spoken in regions adjacent to Kashmir, showing only that the Sanskritic-Avestan homeland would at least include Kashmir. The neighboring nations which speak Sanskrit-like languages are the Kalashi, Shina, Gawar Bati, Dameli, Pashayi, Kohistani, Palula and Nuristani. Just as in Avestan, 'zarat' means golden and 'ustra' refers not only to camel[162] but also to wild animals such as cows and sheep in general[163], as well as buffalos. 'Ustra' is used a few times in the Atharva Veda), displaying the point that camels and buffalos were very familiar and common amongst where the Veda's compilers and where Zarathustra lived.

- Why Zarathustra left for Balkh

"That this Magian language was Zend is surely no forced hypothesis, since from those Brahmins seated in Bactria, we long after find Zoroaster bringing the same religious system and employing their Zend terms for it: a fact which no one can deny." - John George Cochrane[164]

In ancient time, Indian Brahmans had a great amount of influence over the kingdoms adjacent to India or ones that extended from India to other places like Gandhara, Kakeya, and Kamboja. The fact that Athravans are the chief priests of Mazdaean in Afghanistan implies that Brahmans were already established in the region before Zarathustra's arrival there. In the Vedic Era, King Atyarāti Jānaṃtapi conquered Uttara-Kuru, thus bringing more Indian influence to Central Asia and it shows the level of influence that India had. In the 3rd century BCE it was Asoka who had it under his dominion, and in the 8th century CE, it was Kashmiri king Lalitaditya Muktapida that had suzerainty over it. Balkh was known to have a Brahmans within the court of its king as well. Historically in India, Brahmans and other spiritual teachers have sought royal patronage to institutionally aid their religions such as in preaching beliefs to society and building temples. They would become rajyagurus (royal teachers) or rajpurohits (royal sacerdotal priests.) Zarathustra had become the chief spiritual adviser of the Balkhan court and his family members who were the first Mazdaens and also had similar positions within the court. Ancient Greek historian Aelianus in De natura animalium,[165] also mention that there were "Indian Arianians" and there is some suggestion that control of Ariana fluctuated between Indian and Arian Arianians. This infers that Indians in Ariana had political influences.

"A Rishi went to another country, to try and get his name famous there as a Rishi, but he got less celebrated than before (in his own country.) O Rishi, you left your home without a cause."[166] - A Kashmiri Proverb

Kashmir being Land of Rṣis was abundant in rṣis and it was normal for a monarch of ancient Balkh and other regions of Afghanistan to have Brahman teachers or ministers from India. For example, Nagasena (another Kashmiri) had become the preceptor of the Balkhan King Menander, while Aśvaghośa and Nagarjuna[167][168] (another Kashmiri) of Balkhan King Kaniṣka[169] who after his conversion held the Fourth Buddhist Council in Kashmir. Buddhayasas was a Kashmiri and had become the preceptor of Dharmagupta the king of Kashgar in 5th century CE. Gunavarman was a prince of Kashmir but was missionary for much of his life and became the royal adviser to the kings of East China, Java, and Sri Lanka in the 4th century CE. Shakyashri Badhra, Ratnavera, and Shama Bhatta were Buddhist missionaries to Tibet and East China. Bilhana was a royal sage of Panchal's King Madanabhirama in the 9th century CE. Even the Hindu Shahi Dynasty was established in the 9th century CE by the Turki Shahi Dynasty's Brahman minister Kallar.[170] King Minar Dhitika was converted to Buddhism by Sangabhadra. King Seve Salbar of Afghanistan was converted to Bonpo by Namse Chyitol. Kashmir was influential to both Indian and adjacent regions. In ancient history, Kashmir has been part of various kingdoms that had included regions of Afghanistan. Even in the Buddha's time, Gandhara (Punjab region and neighbouring Afghan lands westwards) was a Mahajanapada, according to Bauddh scriptures[171] and in many periods of history, Kashmir was a part of the Gandharan Kingdom. The very scripts that ancient Afghanistan adopted royally were from India, Kharoshthi (Gandhara-lipi), then Brahmi, then Sharada, with the last one being of Kashmiri origin. One can see, then the scale of intellectual influence on Afghanistan from India (Kashmir in particular.)

The presence of Indian Brahmans in various places, including neighboring ones, such as Gandhara and Balkh, was recorded in ancient times; Edict 13 of the 14 'Rock Edicts of King Asoka' reads, "There is no country, except among the Greeks, where these two groups, Brahmans and ascetics are not found and there is no country where people are not devoted to one or another religion..." Along the ancient Silk Route the Kashmiri gateway is at Kunjerab Pass and the Balkhan gateways on the pathway are Balkh and Shahrisabz.

Areas of Afghanistan being under the influence of Indian dynasties made Balkh a friendly place for Zarathustra to be a Brahman priest in.

- Routes from Kashmir to Afghanistan

Kashmir, bring the crossroads of civilizations in the ancient times, witnessed much traffic from various countries. Caravans passed through and used Kashmir as a pathway. Abu Fazl wrote that there are a network of routes connecting Kashmir with India alone.

The likeliest route Zarathustra would’ve taken to Balkh is the Baramulla-Pakhli route. Not only because he was of Baramulla and would’ve been more familiar with this route but because it was the shortest line of communication to the Indus Valley and Hazara and thence into Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Iran. Chinese emissaries Hsuan Tsang and Ou-k'ong took this route on their way to Kashmir. Hsuan Tsang specifically took the route from Balkh, Kapishi, Nagarahara, Purushapura, Pushkaravati, Udabhanda, Taxila (Gandhara), Menki (Uddiyana), Darel, Bolor, Udabhanda, Usara, finally to Kashmir.[172]

The next most popular route that connected Kashmir to anywhere else was the Bhimber-Hirpur route, which connected Kashmir and Punjab. Punjab (Gandhara) was, as shown previously, used by many peoples to enter Kashmir.

Two other routes connecting Kashmir to Central Asia and China were the Karnah-Chilas and Gurez-Baltistan pathways, both very close to Kashmir.

The Wakhan Corridor, which liked northern Kashmir with N.E. Afghanistan and Tajikistan, was used as another route.[173]

Hamid Wahed Alikuzai mentions northern routes that connect India and Central Asia that pass specifically through Kashmir and Afghanistan via “defiles of Chitral.”[174]

Identification of other places in India[edit]

Because Mazdaen texts identify other areas adjacent within India, especially ones adjacent to Airyanem Vaeja, it reaffirms that Zarathustra's holy land is in Kashmir.

- Ātaro-Pātakān of the Avesta is not the Azerbaijan of Caucasus

Ātaro-Pātakān means Keeper of the Fire, which Sanskrit scriptures have used as 'Pāthaka Pitta'. Pāthakām is Sanskrit has meant to be a canton wherein specifically priests live.

Ātaro-Pātakān is the region of Himachal-Uttarakhand. In Mazdaen scripture, Ātaro-Pātakān is known for having the Asnavand Mountain and the city of Rak from where Zarathustra's mother was from. The Avestan Vendidad[175], it is Rak, whereas in Pahlevi scriptures it's Rag or Arak.

Mazdaen scripture says that in this region is the holy Atur-Gushnasp, a shrine of an eternal-burning flame. The Atur-Gushnasp is the Jawalamukhi Temple of Mandi district of Himachal Pradesh.

Arrian [176], Strabo[177], Pliny[178], and Justin had stated that Atropatene in Media was named after its Satrap Atropatos declared independence after Alexander's death. He ruled the region under Alexander of Macedon from 328-327 BCE.

Because the Avesta predates Satrap Atropatos, the region of Atropatene is not the Avestan Ātaro-Pātakān (Protector of the Fire.) The Avestan Ātaro-Pātakān is in Persian known by 'Adar-bigan'. Hence, when the kingdom of lower Media took on the name Atropatene, it's Persian-equivalent name also began being used, and in the predominant Turkic language there it became known as Azerbaijan.

That Ātaro-Pātakān borders Airyanem Vaeja is seen in multiple sources, including the Bundahishn.[179]

| Zarathustra's father was of the region Adarbaijan; his mother whose name was Dughdo came from the city of Rai. | ||

—Shaharastani | ||

In the verse above it’s interesting that Zarathustra’s mother’s name is Dughdo, which means Milk-maiden, and a Kashmiri stream of the Jhelum that is now called the Dudhganga has historically been called Dughdasindhu[180]. A fort in the very north of the Kashmir Valley, near Gurez, was called Gughda-ghat. These example shows that Dughda was used as a name in ancient Kashmir.

- Aredvi Sura (Sataves) River is Sutlej

| And Sataves itself is a gulf (var) and side arm of the wide-formed ocean, for it drives back the impurity and turbidness which come from the salt sea, when they are continually going into the wide-formed ocean, with a might high wind, while that which is clear through purity goes into the Aredvi Sura sources of the wide-formed ocean. | ||

—Zadsparam 6.16[181] | ||

Sataves' fluvial properties are also elaborated when Bundahishn and Vendidad Fargard[182] state that Sataves controls the tides of Vouru-Kasha.

Just as how the Daiti being a tributary of the Indus is called Veh-Daiti, so too is the Aredvi Sura called the Veh-Aredvisur as the Sutlej is also an Indus tributary.

- Chakhra is the Kishanganga Valley

Listed as 1 of the "16 Holy Lands" in the Avesta, it was historically where the Chak Dynasty of Dardistan existed existed, being a sister dynasty of the Chak Dynasty that ruled in the Kashmir Valley.

Chakra is even mentioned as a kingdom within India in the Mahabharata. The text mentions, "the Chakras, the Chakratis," so because the Chak Dynasty of the Kashmir Valley is a successor of the one from Kishanganga Valley, the Chakras mentioned were the rulers of the Kishanganga Valley and the Chakratis the rulers of the Kashmir Valley.

Hasan mentions the Chaks of Gilgit originating from the ancestor of Helmat Chak.[183]

- Gaokerna is Gokarna

Mazdaean scriptures mention the Gaokerna tree of immortality, which is the same as the Hindu Gokarna.

There are said to be 2 Gokarna places; A northern and a southern.

The Varaha Purana refers to Gokarna, as a region where the shrine of Lord Gokarna was installed at the confluence of the Sarasvati and the Yamuna.

- Hapta Hindava

| Oh Ganga, Yamuna, Sarasvati, Shutudri, Parushni, follow my praise! O Asikni, Marudvridha, Vitasta, with the Arjikiya and Sushoma, listen! | ||

—Rig Veda 10.75 | ||

There is a general academic consensus that Hapta Hindava, Hapta Hindu, or Hapta Hendu were names that Mazdaean scriptures used for most of the northwestern region of India south of the Indus' Arjikiya (Haro River.) This is the same Sapta Sindava mentioned in the Rig Veda. The question arises, 'What were the rivers defining the boundaries of Sapta Sindava?' Because the Gomal and Kabul tributaries of the Indus River were already identified as Sigistan and Vaekreta, the Sapta Sindava couldn't have included areas west of the Indus. In the Nadistuti Sukta of the Rig Veda, a verse mentioned 10 rivers, among which Indus (Sindhu), its tributaries Asikini (Chenab), Parushni (Ravi), Susoma (Sohan) Shutudri (Sutlej), Vitasta (Jhelum), and the Sarasvati (Ghaggar-Hakra.)

What confuses historians and archaeologists is that if the Sarasvati River is in the Indian Subcontinent, then why Haetumant (modern Helmand or Arachosia region) was referred to as 'Harauvatish', which is etymologically a derivative of Sarasvati. Historically, as Indians (Hindu, Bauddh, Bonpo, and Jain missionaries) moved westwards out of India, they influenced the places they went and places then became named after areas in India. For example, although there is a consensus that the Mazdaen Veh is the Indus, a Mazdaen scripture also mentions that the Amu Darya was called Veh. There are also places in Afghanistan named Hindu Kush, Hindvar, Kamdesh (named after Kambohs[184]), Kandahar (named after Gandhara[185]), Kapisha (named after Kalishthala or Kaithal), Kunhar (named after Kunhar River), and Punjab. Baluchistan has also been called Sind. The Greek historian Isidore writes that the Parthians even called Arachosia (Harauvatish) 'White India', showing Indian influence there[186]! It is also noteworthy that no Mazdaen scripture or any text ever mentions a river named Harauvatish - it's only a name of the Arachosia region. Further, the Sarasvati River itself in Mazdaen scriptures was called Aredvi Sura. According to the records of the war between Alexander of Macedonia and Achaemenid Empire’s Satrap Barsaentes, the latter escaped to the 'Indians' in eastern Arachosia, from where he received a new military battalion of 'Mountaineer Indians' . So it’s clear that Arachosia was heavily Indianized.

- Kangdez is Gangdise (beside Kashmir)

From the geography of Mazdaen scriptures it is easy to determine the location of Airyanem Vaeja in Kashmir because the regions around Airyanem Vaeja are mentioned too. The part of Tibetan Plateau west of the Indus River and Brahmaputra is even today called Gangdise. Mazdaen scriptures and the Shahnameh mention Kangdez.

In the Dadestan-i-Menog-i-Khrad[187], the location of Kangdez is described as "Kangdez is entrusted with the eastern quarter, near to Satavayes on the frontier of Airan-vego." Since Kangdez is the Gangdise region, this excerpt also supports Kashmir being Airyanem Vaeja.

Turkish historian Al-Biruni writes that he cannot locate Kangdez and that both Yamakoti and Tara are cities there. Yamakoti is also mentioned in the Srimad Bhagavatam.

| It is said that Bhadrasva-varṣa extends from the city of Yamakoti up to the Malyavat Mountain. | ||

—Srimad Bhagavatam | ||

The prominent mountain associated with this continent is Malyavat Mountain. It is the modern-day Muztag (7,282m) because the Mahabharata identifies Meru as being between the Malyavat and Gandhamadana.[188]

Apart from the Mt. Meru (Mazdaen Hara), Mt. Kailash is also revered in Mazdayasna as "Kangri". It is the abode of Peshotan (Chitro-maino), son of King Vishtaspa, and Khwarsheed-chihr (Khursheed-chehr), son of Zarathushtra, who will gather their righteous army there before the final battle against Ahriman and his creatures, according to the Bundahishn[189], Denkard[190], Zand-i-Wahman Yasn[191].

Kangdez means "Fortress of Kang." In Ferdowsi's epic Shahnameh, Kangdez is named as Gangdez.

Kangdez's name is related to Kangha mentioned in the Avestan Yasht 5.54, the Aban (Aredvi Sura) Yasht. Antar Kanga is part of a list of mountains in Yasht 19.4. Antar Kanga is the chief mountain on which Kangdez bases its name, and is the largest mountain in the Gangdise, Mt. Kailash.

- Kangdez contains Rasātāla

Just as Vasuki is mentioned as the ruler of Rasātāla, the children of Vaesaka are mentioned in the Shahnameh as rulers of Kangdez. Just as Vasuki is of a serpent tribe, Vaesakas are written of as worshiping serpents.

| To her did Yoista, one of the Fryanas, offer up a sacrifice with a hundred horses, a thousand oxen, ten thousand lambs on the Pedvaepa of the Rangha. | ||

—Aban Yasht 20.81 | ||

Pedvaepa river, an affluent[192] of the Ranhā is the Pedak-miyan of the Bundahishn.

| The Pedak-miyan, which is the river Katru-miyan, is that which is in Kangdez. | ||

—Bundahishn 20.31 | ||

- Mainakha of Avesta is Mainaka of Puranas

As the names are almost identical they are the same mountain. The Mahabharata claims it was north of Mt. Kailash.[193] It is known as Mt. Kangrinboqe Feng (6,656m) in Tibet, north of Mt. Kailash (7,694m.)

- Ranhā is Rasā

- See also: Areas of Asura control

The Avesta mentions Ranhā (Sanskrit: ' Rasā', another name for Rasātāla), which is the "sixteenth of the best lands created by Ahura Mazda." This land is based around the sources of the Ranhā River which is the Rig Vedic Rasā River. This river is identified with the modern-day Brahmaputra River because the scriptural traits of the Rasā mentioned align with those of the Brahmaputra. Rasātāla, being populated by many Daityas (i.e., Ahuras) would be of significance to Mazdaens and it always appears on the lists of 7 main abodes of the Asuras. Here a major battle between Asura and Deva took place, the battle of Hiranyakṣa and Varāhā. The Markendaya Purana even mentions the Rasalaya as a peoples in Bharat-varsa as it does the Sarasvats.

Two Avestan Fragards mention that Ranhā is the largest river that they know. This is true because Ranhā (Brahmaputa) is 3,848km while Veh (Indus) is 3,610km.

Three affluents of the Ranhā are named in the Yashts; Aodhas[194], Sanaka[195], and Gaudha[196]. The Brahmaputra passes through Gauda (Bengal) region and hence, a Ranhā tributary would be named Gaudha. This is likely the Jamuna River.

| We sacrifice unto Mithra, the lord of wide pastures, ....sleepless, and ever awake;

Whose long arms, strong with Mithra-strength, encompass what he seizes in the easternmost river and what he beats with the westernmost river ("Hindu"), what is by the Sanaka of the Rangha and what Is by the boundary of the earth. |

||

—Khorda Avesta 27.104[197] | ||

- Vouru-Kasha is Indian Ocean

Its other names in Mazdaen scriptures are the Frakhvkard and Varkash. Both the names Vourukash and Varkash are reflective of the other name for Indian Ocean city Bharuch, Varukaksha.[198]

Just as the Indian Ocean in Hindu scriptures is referred to as the "Sea of Salt" so to the Khorda Avesta[199] calls the Vourukasha, the "deep sea of salt waters."

Practice of similar customs[edit]

There are customs that are typically unique to the Mazdaens, but were practiced in India. Some of the customs within the Mazdaen community are similar to those of the Hindu Brahmans. For example, the Navjot and vegetarianism.

Spiritual initiation[edit]

"The investure with the Kosti, as described in the Yesht Sade, and alluded to in several places of the Vendidad, appears to be nothing more than the Kaksha, or girdle of the Hindus, blended with some notion of the cord, or Upavita." - The Quarterly Oriental magazine, review and register[200]

Navjot which means new birth is the initiation of a Mazdaen and they are given a sacred thread to wear similar to that of the Yajnopavita ceremony for many Hindus.

Just as the Mazdaen ceremony marks a 'new birth', the Hindu one also does the same. Hence, anyone who receive the Hindu ceremony is called a 'dwija' (twice-born.)

Vegetarianism[edit]

| I allow the good spirits who reside on this earth in the good animals to go and roam about free according to their pleasure. I praise, besides, all that is offered with prayer to promote the growth of life. | ||

—Yasna 12.3, Gāthās, Zhand Avesta[201] | ||

A large section of Parsis[202] are vegetarian and during weddings/navjyots, there is always a "Parsi vegetarian" menu. There are four days in a month where all Mazdaens, even the non-vegetarians are expected not to eat meat in a practice called parhezi which means abstinence. They are Bahman, Mohar, Ghosh, and Ram roj. Meat is also not eaten for three days after a relative passes away.

| Be plant-eaters ('urwar khwarishn', i.e., vegetarian), O you people, so that you may live long. And stay away from the body of useful animals. As well, deeply reckon that Ohrmazd the Lord, has for the sake of benefiting useful animals created many plants. | ||

—High Priest Atrupat-e Emetan (Adarbad, son of Emedan) who officiated after the Arab invasion states in the 11th century CE, Book 6, Denkard | ||

Third century CE Greek biographer, noted in the prologue to his Biography[203] that the Magi priests of Persia "dress in white, make their bed on the ground and have vegetables, cheese and coarse bread..."

The modern Ilm-i Khshnum movement in India advocated vegetarianism too.

Dr. Kenneth S. Guthrie believed that Zarathustra promoted vegetarianism.[204]

Usage of plants in worship[edit]

Both Mazdaens and Hindus use plants in their worship. During group and individual praying, Mazdaens hold a plant. Also, in the Haoma ceremony of Mazdaens, they use the ephedra in the ritual.[205]

Usage of bells in worship[edit]

Mazdaen temples ring their bell during 5 prayer sessions in a day.[206] Some priests ring the bell 9 times a session. Bells are very common in Hindu temples too.

Venerating the same persons[edit]

In Mazdayasna, Ahura Mazda is the Supreme Lord and the other supernatural beings are yazatas.[207] As there are several with a similar name in both Mazdayasna and Hinduism, there are also others whose names are different but are the same persons, such as Sraoesa, who is Bṛhasa of Hinduism.

- Varuna

- See also: Varuna

"Ahura Mazda has created asha, purity, or rather the cosmic order; he has crested the moral and the material world constitution; he has made the universe; he has made the law; he is, in a word, creator (datar), sovereign (ahura), omniscient (mazdao), the god of order (ashavan). He corresponds exactly to Varuna, the highest god of Vedism."[208] - Arthur Lenormant

In the Rig Veda, though Varuna remains a god, his influence lessened as many gods took the side of Indra as their king and many humans took him as their chief god.

| Many a year I have lived with them; I shall now accept Indra and abjure the Father Varuna, along with his fire and his soma (haoma) has retreated. The old regime has changed. I shall accept the new order. | ||

—Rig Veda 10.12.4 | ||

| Varuna | Ahura Mazda |

| "I made to flow the moisture-shedding waters." | "Rain down upon the earth to bring food to the faithful and fodder to the beneficial cow." |

| Rig Veda | Vendidad |

The Vendidad is called in Pahlevi the Zhand-I Jvit Dev Dat. Here the 'Dev Dat' portion of the title refers to the conch of Ahura Mazda. The Dev Dat is mentioned in Hindu scriptures as the conch of Varuna.

There is a strong connection in Hindu scriptures between Varuna and Asuras. For example, the Mahabharata mentions that he receives homage in his palace by asuras. He is also said to live in the sea (any body of water other than a river) with Nagas, and his residence there is known as Asuranam Bandhanam. Then according to the Valmiki Ramayana, Ravana had invaded Rasātāla where lived Varuna, his sons, Nagas, and Daityas. According to the Srimad Bhagavatam[209], Hiranyaksha visted Varuna to seek his advice on whether to fight Vishnu or not (in which Varuna advised the Daitya king to do so to earn Vishnu's grace by being slain by him.) Hiranyaksha there had called Varuna "Adhiraja" (Supreme Lord!) The Mahabharata claims that Varuna governs Rasātāla, 1 of the major strongholds of the Asuras. Hiranyapur, another stronghold (where Prahlad Maharaj governed from) was also affiliated with him. Further, Varuna is the one of the few gods that have Asuras as administrators. Varuna's are Meghavasas in his assembly, and another named Sunabha.

| O Yudhishthira, without anxiety of any kind, wait upon and worship the illustrious Varuna. And, O king, Vali the son of Virochana, and Naraka the subjugator of the whole Earth; Sanghraha and Viprachitti, and those Danavas called Kalakanja; and Suhanu and Durmukha and Sankha and Sumanas and also Sumati; and Ghatodara, and Mahaparswa, and Karthana and also Pithara and Viswarupa, Swarupa and Virupa, Mahasiras; and Dasagriva, Vali, and Meghavasas and Dasavara; Tittiva, and Vitabhuta, and Sanghrada, and Indratapana--these Daityas and Danavas, all bedecked with ear-rings and floral wreaths and crowns, and attired in the celestial robes, all blessed with boons and possessed of great bravery, and enjoying immortality, and all well of conduct and of excellent vows, wait upon and worship in that mansion the illustrious Varuna, the deity bearing the noose as his weapon. | ||

—Section 9, Mahabharata[210] | ||

While the Rig Veda directly calls gods out as Asuras, it also indirectly refers to Varuna as an "Asura of heaven"[211], and latter verse heaven itself is called 'asura'[212]. Also in a verse in which Asura is mentioned, it reads, "our father pours down the waters."[213] Further, the RV says that Agni is born from his (the Asura's) womb.[214] This is important in showing that Agni is a child of Varuna just as the Holy Fire (Atar) is mentioned as the son of Ahura Mazda in the Avesta.

Like Varuna[215], Ahura Mazda is connected to shepherds. When Zarathustra had asked which kind of man enjoys the earth most, Ahura Mazda replied it was the agrarian.[216]Ahura Mazda in the Avesta declares for Aredvi Sura to keep all sentient creatures “just like a shepherd keeps his flock.” Even a Georgian legend states that in pre-Christian times, laypeople would offer sacrifices to the god they called 'Armazi' (Ahura Mazda) by the 'bridge of the magi', and that at night shepherds called on Armazi for help.[217]

Ahura Mazda's connection to Vahiśta goes back to Varuna's relation to Vasiśṭha from Hindu scriptures. For example, The Ramayana mentions that Vasiśṭha was a son of Varuna through Urvashi born at Varunalaya (modern Barnala, Punjab.) He was also said to have turned his son Vahiśta into a scholar by simply accompanying him on a boat trip. Varuna had taught what is called "Bhrgu-Varuni Vidya" to his son Bhrgu of which the essence was "Brahm (God) is nothing but joy."

The name 'Zarathustra' means Golden buffalo, which is because the animals involved in sacrifices to Varuna were usually buffaloes[218] (at least metaphorically.) This is akin to Hindus being named after a vehicle of god, such as Basava or Nandi, the bull of Shiva. These names reflect devotion and subordination as servants of gods.

- Kavi Uṣana

An Ahura of Mazdayasna is known as an Asura in Hinduism. It is then no surprise that we also find Śukra Acharya or Kavi Uṣana, the Guru of the Asuras, being venerated as one of the most holy beings. His connection to Varuna in Hindu scriptures is that he is Varuna's devotee in many instances as seen in Satapatha Brahmana[219]. In the Avesta he is known as Us and later in the Bahram Yasht as Kavi Uṣa.[220]

| This one is known to me here, who alone heard our precepts: Zarathustra, the Holy, he asks from Us, Mazda, and Asha, assistance for announcing, I will make him skilful of speech. | ||

—Yasna 29, Zhand Avesta | ||

Kavi Uṣa is also called Kava Uṣan and Ashvarechao, which means full of radiance just like how his Hindu name Śukra means radiant and how scriptures like the Yoga Vasiśṭha[221] describes him as "radiant young Śukra", or Ramayana[222] describes "Śukra, radiant as the sun, departed."

The Avesta doesn't refer to him as Śukra because that name is reserved as an epithet for Ahura Mazda, who is invoked as, "athra sukhra Mazda"[223] (Kavi Uṣana has many titles.)

Uṣana is also given importance because he descends from Angiras. Mahabharata reads that Kavyas descendants from Kavi.[224] Manu Smriti establishes a Kavi as a descendant of Angiras.[225] Like how Uṣana is a regent constellation in Hindu astrology, he is a star included among the Great Bear constellation, in the Hapto-iringas of the Avesta.[226]

- King Ram

- See also: Rama

Mazdaen scriptures mention a righteous monarch named Ram, whom it addressed Ram Khshatra. Though it doesn't dive into details about the yazata, it usually mentions him together with Mithra. In Hinduism, he is known a Raja Ram, a noble king, "Arya that cared for the equality of all", descendant of Mitra.

| Rama, descendant of the sun ("Mitra"), became friends ("mitra") with Sugriva, son of the sun ("Mitra.") | ||

—Ramayana, 15.26 | ||

There is even one passage in the Avesta that mentions Ram together with Vahiśta, which is symbolic of the relationship in the Ramayana that Ram has with his guru Vasiśṭha[227]. It also shows the relationship between Mithra and yazata Ram.

| We sacrifice unto Mithra, the lord of wide pastures; we sacrifice unto Rama Hvastra. We sacrifice unto Asha-Vahiśta and unto Atar, the son of Ahura Mazda. |

||

—Khorda Avesta 2.7 | ||

Sacredness of the sun[edit]

The sun is like fire, a holy symbol of Ahura Mazda. The Avesta declares:

| This Mithra, the lord of the wide pastures, I have created as worthy of sacrifice, as I, Ahura Mazda, am myself. | ||

—Avesta | ||

Mitra is a god often paired with Varuna in Vedic hymns. There are many Hindus today who worship God Almighty in the form of the sun and they are known as Sauras. The Māga Brahmaṇas are very closely associated with the sun-worship in Hinduism.

Just as the Rig Veda declares that the sun is the "Eye of Varuna"[230], the Avesta[231] it also declares that Mitra is the eye of Ahura Mazda.[232]

Prayer terminology[edit]

Just as Hindus include the word namo in their mantras, such as 'Namo Varunaya'[233][234] or 'Namo Jinanam', Mazdaens too apply the term in the phrases 'Namo Ahurai Mazdai', 'Namo Zarathushtrahe Spitaamahe', 'Namo Amesha Spenta' and 'Namo Heomae'.

'Nemase-te' is another term used by Mazdaens which is the equivalent of Sanskritic Namaste.

'Neueediem' has the Sanskritic equivalent 'nivedayami', which has been used in Hindu verses like "Om Owing Saraswatai nivedayami."

Praying ceremony for departed ancestors[edit]

Both Mazdaens and Hindus offer prayers for their ancestors, and the procession meant solely for their well-being is known as the 'Dhup Nirang' (Gujarati for ritual of offering of frankincense) or 'Nirang-e Rawan-e Guzashtagan' (Persian for Ceremony for the souls of departed ones) amongst Mazdaens[235] and as 'Śrāddha' amongst Hindus.

Corresponding festivals of Mazdaens and Kashmiri Hindus[edit]

Just as Mazdaens celebrate Ahura Mazda (Varuna) and King Jamshed, so too do Kashmiri Hindus. The Mazdaen calender new year, celebration Nuvruz, is the same festival as that of the Kashmiri Hindus, Navreh.[236]

During the festivity of Tararatrih, on the 14th of the dark half of Magha, King Yama is worshiped.[237] On Varuna Panchami, Varuna is worshiped.[238] Varuna is worshiped again on the 5th day of the festivity of Yatrotsava, whereby Hindus are encouraged to visit his 'abodes' or temples.[239]

Celebrating god Mitra has historically also been a part of Kashmiri culture. Till the 11th century CE, the Kashmiri Pandits celebrated Mitra (Mithra) Punim, on the fourteenth or full moon night of the bright fortnight (Śukla Pakṣa) of the Hindu autumn month of Ashvin or Ashwayuja. Similarly, the Mazdaens celebrate Yalda as the birth of Mithra.[240]

Usage of fire in ceremonies[edit]

Fire is used in processions of both Mazdaens and Hindus. Their temples use fire altars for performing the rituals. Fire altars have been discovered in the Indus Valley city of Kalibangan in northern Rajasthan state, showing that even the ancient society then revered fire as sacred.

Fire Hindu temples also exist in the Himalayas wherein flames are constantly burning.

- 3 significant fire-temples

- Jawalaji Bhagvati (Khrew, Kashmir)

- Jwalamukhi (Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh)

- Jwala Mai (or Salamebar Dolomebar Gomba or Mebar Lhakang Gomba in Muktinath, Nepal)