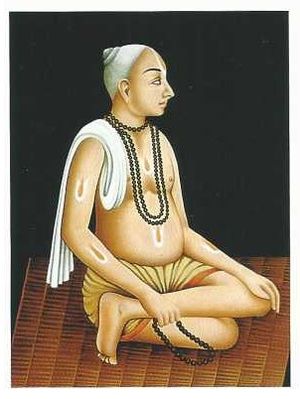

Tulasīdāsa

By Swami Harshananda

The Rāmacaritamānasa[1] is one of the few great religious works that have revived and sustained religion. It has also instilled life and power in the society of its times. The immortal author of this monumental epic is Tulasīdāsa.[2] He lived in A. D. 1496-1622.

Journey from Childhood to Upanayāna[edit]

According to the popular oral tradition, he was born as the son of Ātmārām-dube and Hulasī, a brāhmaṇa couple, at an inauspicious moment in A. D. 1496, corresponding to the Vikramaśaka 1554. Hence he was abandoned by the parents. He was brought up first by an old servant maid and later by a beggar woman. When he was about eight years old, a sādhu[3] named Narahari Ānanda saw him and recognized his inherent greatness. He took him away to his āśrama.[4] He named the boy as Rāmbolā and started training him by narrating the story of Rāmāyaṇa. At the time of his upanayāna,[5] Rāmbolā was given the new name Tulasīdāsa by his guru and mentor.

Higher Education and Ascetic Training[edit]

Tulasīdāsa was then sent to Kāśī for higher education under Seṣasanātani, a great scholar and an eminent teacher. After a vigorous course of education in the Vedic lore, allied literature and training in austere life spread over fifteen years, Tulasīdāsa returned to Rājpur, his native place. There, he started spending most of his time delivering religious discourses based on the Rāmāyaṇa.

Turning Point[edit]

He was married to Ratnāvalī, the learned and beautiful daughter of a well- known astrologer Dīnabandhupāthaka. He was passionately attached to her. However, this attachment was shaken by her as she admonished him and advised him to direct his love towards the Lord Śrī Rāma. As a result of this shock, Tulasīdāsa renounced the world then and there and came to Kāśī. There he started giving discourses on the Rāmāyaṇa which became extremely popular.

Composition of Rāmacaritamānasa[edit]

At Kāśī, Tulasīdāsa was lucky enough to meet Hanumān[6] and have the darśan[7] of Śrī Rāma. As per the direction given by Lord Śiva in a vision, he went to Ayodhyā and started writing his magnum opus, the Rāmacaritamānasa in the local dialect called Avadhi. It was completed in about two and a half years. The excellence of this composition roused the jealousy of other scholars who tried their best to harm him but failed miserably.

Other Contributions[edit]

He now started the real work of his life, spreading Rāma’s story and his powerful name. He also organised the youth of his times to become strong, both physically and morally, by starting a number of akhāḍas[8] and recruiting them. Hanumān was projected as their hero. He also built a number of temples of Hanumān. He passed away at the age of 126 years in A. D. 1622 at the Saṅkatmocan-ghāṭ[9] on the bank of the river Gaṅgā in Kāśī.

Other Literary Works[edit]

Apart from the Rāmacaritamānasa, eleven more works were written by him. Among them the following are more well known:

- Vinayapatrikā - The Vinayapatrikā is in the form of a petition to the king Rāma seeking protection from the threats of Kali.[10]

- Kavitāvali - The Kavitāvali is in a language which is a mixture of Avadhi and Brajbhāṣā.[11] It is based on the main work Rāmacaritamānasa and acts as a supplementary.

- Dohāvalī - The Dohāvalī is a work of verses of two lines containing the teachings of the author based on his experiences, interspersed with the story of Rāmāyaṇa.

- Rāmājñapraśna - It is a very interesting but recondite work aimed at providing solutions to our problems if used in the recommended way.

References[edit]

- ↑ It is also spelt as Rāmcaritmānas.

- ↑ The name is also spelt as Tulsīdās.

- ↑ Sādhu is a holy man.

- ↑ Āśrama means monastery.

- ↑ Upanayāna means initiation into Vedic studies and religious life.

- ↑ Hanumān is supposed to be a cirañjivi, living eternally in a subtle body.

- ↑ Darśan means seeing.

- ↑ Akhāḍas means native gymnasia.

- ↑ It is a place for bathing.

- ↑ He is the Master of the Iron Age.

- ↑ These languages are variants of Hindi.

- The Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Swami Harshananda, Ram Krishna Math, Bangalore