By Swami Durgananda

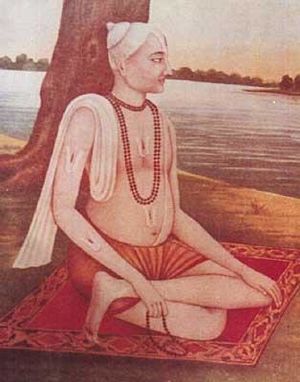

Sant Tulsidas was a mahatma whose heart melted in the white heat of love for God, whose pure, home-spun, and simple longing for God was to show direction not only to a few individuals, but to humankind at large; not only to one particular nation, but also across all borders; not only for a decade or two, but for centuries. Such saints do not direct just a small number of persons but wake up the divine consciousness in all humanity.

The Beginning[edit]

In sixteenth-century Rajapur—about 200 km east of Allahabad—in the Banda district of Uttar Pradesh, there lived a rather gullible brahmana couple: Atmaram Dube and Hulsi Devi. Tulsidas was born in the year 1532 after 12 months in his mother's womb and with a full set of teeth.

Under which unfortunate star this child was born is not known for certain. But it is believed that it was the asterism mula that was on the ascent then—a period of time known as abhuktamula. According to the then popular belief, a child born during abhuktamula was destined to bring death to its parents. The only remedy, it was believed, was for the parents to abandon the child at birth—or at least not to look at it for the first eight years!

The utterly poor father had nothing in his house for the celebration of the child’s birth or for the naming ceremony. Meanwhile, the mother died. Weighed down by circumstances and superstition, the father abandoned the child. Chuniya, the mother-in-law of the midwife who had helped during the birth of the child, wet-nursed him. Such was the child’s fate that Chuniya too died after five years and he was left wandering, looking for morsels of food here and there, taking occasional shelter at a Hanuman temple. This was the boy who would later be recognized as Sant Tulsidas and excite bhakti en masse with his soul stirring couplets.

Biographical Sources[edit]

The penchant of saints for self-abnegation and their aversion to renown and recognition make it difficult for biographers to obtain details about their lives. This is also true of Tulsidas. There are several biographies with varying levels of authenticity.

- Benimadhavdas, a contemporary of Tulsidas, wrote two different biographies: Gosai Charit and Mula Gosai Charit, the latter including more incidents. However, these books contradict each other and the biographies written by others.

- Tulsi Charit, a large volume of undated origin, was written by Raghuvardas. Although this work contains a lot of information, it cannot be accepted in toto as it too contradicts Tulsi’s own works and those of other writers.

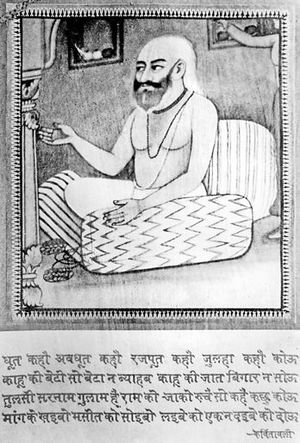

- The Gosai Charit, believed to have been written in 1754 by Bhavanidas, is another biography. However, from Tulsi’s own works, and through commendable scholarly research, a lot of information has been gathered about his life. But in his own works Tulsi gives no information about his youth or the grihastha period of his life. He does not even tell us his father’s name, though his mother does find mention in the Ramcharitmanas: "Tulsidas hit hiyan hulsi si", the story of Ram is truly beneficent to Tulsidas, like [his own mother] Hulsi. [1]

Spiritual Heritage[edit]

The longing for supernal beings is as old as humankind itself. Ancient people worshipped the forces of nature to propitiate them or invoke their power. The Vedas are replete with prayers to Indra, Varuna, Agni, and other such gods. After the decline of the Vedic and Buddhist thought, the bhakti movement was ushered in by a host of saints. Sri Ramanujacharya (1017–1137), who gave bhakti a firm philosophic base and also popularized it, was one of them. Following in his footsteps were a large number of saints from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century. Swami Ramanand (c.1400-c.1470), born in Prayag, played a great role in paving the way for bhakti in North India during this period. Many saints, who ignited and spread the conflagration of bhakti across the land, appeared in the wake of Ramanand’s advent. These included Kabir, the weaver, Dhanna the peasant, Sena the barber, Pipa the king, Raidas the cobbler, and through Raidas, Mirabai. The great Tulsidas too may be counted as belonging to this tradition. Ramanand is reputed to have been the fifth spiritual descendant of Sri Ramanujacharya. We have no record of the sayings of Ramanand, who perhaps preferred to spread the immortal message of bhakti through the radiant and glowing example of his own life. However, one of his songs, included in the Guru Granth Sahib, is evidence of his insight:

Where shall I go? The music and the festivity are in my own house, my heart does not wish to move, my mind has folded its wings and is still. One day, my heart was filled to overflowing, and I had an inclination to go with sandal and other perfumes to offer my worship to Brahman. But the guru (teacher) revealed that Brahman was in my own heart. … It is Thou who hast filled them all with Thy presence. … It is the word of the guru that destroys all the million bonds of action. [2]

Childhood[edit]

Such was the turn of events when Narharidas, a descendant of Ramanand, was commanded in a dream to pick up an abandoned boy and instruct him in the timeless story of Sri Ram. He spotted the boy, who at that time went by the name Rambola [3] , took him to Ayodhya, and completed his sacred-thread ceremony. From a reference to a tulsi leaf used during that ceremony, Narharidas named him Tulsiram, which later became Tulsidas. After about ten months of living in Ayodhya, guru and disciple left for Sukar-khet—or Sukar-kshetra, now known as Paska, near Ayodhya, at the confluence of the rivers Sarayu and Ghagara—where they lived together for five years. It was here that Tulsidas heard the fascinating story of Sri Ram. We can well imagine what fire must have been ignited in the boy Tulsidas when the immortal story of Sri Ram fell upon his pure heart. Another sadhu, Shesha Sanatana by name, now came into Tulsidas’s life and took him to Varanasi, the city of learning. It was here that Tulsi learned Sanskrit, including Panini’s grammar. We read that Tulsi was extremely bright, could remember texts after hearing them only once, and became adept in Sanskrit. That he had a good command of Sanskrit can be known from his few Sanskrit writings and the Sanskrit words, apposite and accurate, thrown casually but widely into his other works.[4]

Marriage and Renunciation[edit]

Tulsidas married a girl whose name was Ratnavali. We are told that the simple couple lived at Rajapur and that their only son, Tarak, died in infancy. Tulsidas was extremely devoted to his wife. This attachment may have been an inchoate form of bhakti—wrongly directed towards a human being—for it was this love, when freed from human attachment, that blossomed into an unbounded love for God. Once, qhwn his wife had started for her paternal home, an infatuated Tulsi rushed behind her at night, across the Yamuna. Upon reaching her, Tulsi was chided by his wife thus:

Hada mamsa-maya deha mam, taso jaisi priti; Vaisi jo sri-ram-mein, hot na bhav bhiti.[5]

Had you for Sri Ram as much love as you have for my body of flesh and bones, you would have overcome the fear of existence.

An apparently simple and innocuous expression of annoyance brought about a conversion in Tulsidas’s mind, which must have already been pure, well disposed, and awaiting the proper hint. Such inner volte-face is not an uncommon phenomenon; innumerable instances have been recorded in the lives of saints of all religions. Tulsidas renounced his house and wife and became a peripatetic monk. He travelled the length and breadth of India, visiting, as he went, the four dhamas and other holy places. Countless souls have been blessed and inspired by his peerless words, and many were raised to sublime heights of spirituality during these peregrinations.

The Ramcharitmanas[edit]

His sojourn finally brought Tulsidas to Varanasi, where he received a divine command to go to Ayodhya and write the immortal epic of Sri Ram in the local dialect.

At a subtle level, legends and myths can carry more of reality than so-called real, sensible, and provable facts. A legend has it that Sri Ram had himself approved Valmiki’s Ramayana by putting his signature on it. After that, Hanuman wrote another Ramayana on stone with his nails and took it to Sri Ram. Sri Ram approved it also, but as he had already signed Valmiki’s copy, he said that he could not sign another, and that Hanuman must first approach Valmiki. He did so, and Valmiki realized that this work would soon eclipse his own. So, by a stratagem, he induced Hanuman to fling it into the sea. Hanuman, in complying, prophesied that in a future age he would himself inspire a brahmana named Tulsi, and that Tulsi would recite his— Hanuman’s—poem in a tongue of the common people and so destroy the fame of Valmiki’s epic. [6] Tulsidas soon went to Ayodhya after receiving the divine command. In a secluded grove, under one of the banyans, a seat had already been prepared for him by a holy man who told Tulsidas that his guru had had the foreknowledge of Tulsidas’s coming. It was 1575, the Ramnavami day. As per legend, the position of the planets was exactly as it was when Sri Ram was born in the bygone age of Treta. On that auspicious day, Tulsidas commenced writing his immortal poem: the Ramcharitmanas.

The composition of the Ramcharitmanas was perhaps Tulsidas’s own sadhana, his act of prayer and offering. It is an expression of creativity that blends the inner and outer worlds with God. It is an inner experience expressed in the form of legend through the medium of poetry. He wrote for two years, seven months, and twenty-six days, and completed it in Margashirsha (November–December), on the anniversary of Sri Ram’s marriage to Sita. He then returned to Varanasi glowing with the bhakti inflamed during the period of writing the devotional epic and began to share his ineffable experience with others. Because of Tulsidas’s good demeanour, loving personality, and exquisite devotion, people would gather around him in large numbers.

That in Varanasi, the stronghold of orthodoxy, erudition, and Sanskrit learning, resistance should develop towards the growing popularity of the unsophisticated Tulsidas is not surprising. Two professional thugs were employed to steal his Ramcharitmanas— with printing not available in those days only a few copies existed. When the thieves entered Tulsi’s hut at night they saw two young boys, one of blue complexion and the other fair, guarding the work with bows and arrows. The terrified thieves gave up their plan and the next day informed Tulsidas of their experience. Tulsidas shed tears of joy, for he realized that Sri Ram and Lakshman had themselves been the guards.

The Vinay-patrika[edit]

A criminal used to beg everyday with the call: ‘For the love of Ram, give me—a murderer—alms.’ Hearing the name of Ram, the delighted Tulsidas would cheerfully take him inside his house and give him food. This behaviour of Tulsi infuriated the orthodox brahmanas, who demanded an explanation. Tulsidas told them that the name ‘Ram’ had absolved the person concerned of all his offences. This attitude of Tulsi incensed the people further. In a fit of anger, they demanded that if the stone image of Nandi—the sacred bull in the temple of Shiva—would eat out of the hands of that murderer, then they would accept that he had been purified. A day was selected for this ritual, and to the consternation of the people, the Nandi image actually ate from the murderer’s hands. The brahmanas were thus compelled to eat humble pie. However, this did not settle matters. This event increased Tulsidas’s popularity even more and enraged the already defeated people afresh, triggering off more attacks and assaults. The troubled Tulsidas then turned to Hanuman for help. Hanuman appeared to him in a dream and asked him to appeal to Sri Ram. Thus was the Vinay-patrika born. It is a petition in the court of King Ram. Ganesh, Surya, Ganga, Yamuna, and others are propitiated first, just as the courtiers would be approached first. Then follows wonderful poetry soaked in bhakti:

He Hari! Kas na harahu bhram bhari; Jadyapi mrisha satya bhasai jabalagi nahin kripa tumhari.

O Hari, why do you not remove this heavy illusion of mine (that I see the world as real)? Even though the samsara is unreal, as long as your grace does not descend, it appears to be real. [7]

Darshan of Sri Ram[edit]

Another legend tells us that Tulsi would pour some water at the base of a banyan tree when he passed that way after his morning ablutions. A spirit that was suffering the effects of past evil deeds lived on that same tree. Tulsi’s offering relieved the spirit of its agony. Wanting to express gratitude to Tulsi, the spirit asked him what he wished. What else would Tulsi want but the holy darshan of Sri Ram? The spirit replied: ‘An old man attends your discourses; he arrives first and is the last to leave. He will help you.’ The next day, Tulsidas identified the man who answered to the description and fell at his feet. The old man told Tulsi to go to Chitrakut, where he would have the darshan of Sri Ram. Who could the old man be but Hanuman himself ? It is well known that Hanuman is always present wherever the name ‘Ram’ is being uttered.

Tulsi remained in Chitrakut, making sandal paste and giving it to the devotees who came there. One day, while he was making the paste, Sri Ram appeared in front of him and said: ‘Baba, give me some sandal paste.’ Tulsi was overwhelmed and went into samadhi. Sri Ram applied sandal paste to Tulsi’s forehead with his own hand. Tulsi remained in samadhi for three days. This was the first time he experienced samadhi—and that through the darshan of Sri Ram himself!

Once during his visit to a temple of Sri Krishna in Vrindavana, Tulsidas addressed the deity: ‘How can I describe your heavenly beauty, O Krishna! However, this Tulsi will not bow to you unless you take a bow and arrow in your hands! ’ In a moment, Tulsi had a vision of Sri Ram instead of Sri Krishna on the altar!

It is believed that the Mughal Emperor Jahangir knew about Tulsidas and that they met at least once. Jahangir pressed Tulsidas to perform a miracle. Tulsi refused saying: ‘I know no miracles, I know only the name of Ram.’ Annoyed at the answer, Jahangir imprisoned him. The legend narrates that a band of monkeys wreaked havoc in the prison and the emperor, realizing his mistake, had to release Tulsi.

The famous pandit Madhusudana Saraswati of Varanasi was a contemporary of Tulsidas. The two devotees discussed bhakti when they met. In an answer to someone’s enquiry, Madhusudana Saraswati praised Tulsidas thus:

Ananda-kanane hyasmin-jangamas-tulasitaruh; Kavitamanjari bhati rama-bhramara-bhushita.[8]

In this blissful forest (Varanasi), Tulsidas is a mobile tulsi tree; resplendent are its poetic blossoms, ornamented by the bee that is Rama.

The End[edit]

Towards the end of his life Tulsidas suffered from very painful boils that affected his arms. At this time he wrote the Hanuman Bahuk, which begins with a verse in praise of Hanuman’s strength, glory, and virtue, and is followed by a prayer to relieve him of his unbearable arm pain. The disease was cured. He passed away in 1623[9] at Asighat, Varanasi. One interesting incident in Tulsidas’s life is quite representative of his teachings. Once a woman, who happened to stay behind after Tulsidas had delivered a discourse, remarked during the course of conversation that her nose-ring had been given to her by her husband. Tulsidas immediately directed her mind deeper saying: ‘I understand that your husband has given you this lovely nose-ring, but who has given you this beautiful face?’

The Ramayana[edit]

The Valmiki Ramayana was Tulsidas's inspiration. It is an epic that is broad in scope and provides guidance for all the stages of one’s life—incidentally, ayana means journey (of life).

Human life, in all its facets and fancies, twists and turns, ups and downs, is on display in the Ramayana. People of different spiritual states derive different light and meaning from the text in accordance with their need and understanding. Ordinary human life can be sublimated and bhakti cultivated through a study of the Ramayana.

The Ramayana of Valmiki includes characters as they are and as they ought to be. Rama, Sita, Kausalya, Bharata, Hanumana, Janaka, and others are ideal characters. Dasharatha, Kaikeyi, Lakshmana, Shatrughna, Sugriva, and others have been presented as beings with mixed qualities. Ravana, Kumbhakarna, and other rakshasas are portrayed as personifications of abominable qualities. Rama plays the role of an ideal son, disciple, brother, master, husband, friend, and king. Subject to human emotions and weaknesses, Rama is a supernal god in human form—but he is also a human who has ascended to be an adorable god.

Rama’s bow and arrow symbolize a force that guarantees peace and justice. Rama’s is the ideal of ‘aggressive goodness’ as opposed to ‘weak and passive goodness’. Rama does not, however, kill or destroy; he rather offers salvation to those he slays in battle. This is technically called uddhara.

There are many other versions of the Ramayana: Adhyatma Ramayana, Vasishtha Ramayana, Ananda Ramayana, Agastya Ramayana, Kamba Ramayana (Tamil), Krittivasa Ramayana (Bengali), and Ezuttachan’s Adhyatma Ramayana (Malayalam), among others. Although these differ in disposition, flavour, emphasis, amount of details, and length of each kanda (canto), they all describe the life of Rama and are inspired by the Valmiki Ramayana.

When Swamiji was at Ramnad, he said in the course of a conversation that Shri Rama was the Paramatman and that Sita was the Jivatman, and each man’s or woman’s body was the Lanka (Ceylon). The Jivatman which was enclosed in the body, or captured in the island of Lanka, always desired to be in affinity with the Paramatman, or Shri Rama. But the Rakshasas would not allow it, and Rakshasas represented certain traits of character. For instance, Vibhishana represented Sattva Guna; Ravana, Rajas; and Kumbhakarna, Tamas. These Gunas keep back Sita, or Jivatman, which is in the body, or Lanka, from joining Paramatman, or Rama. Sita, thus imprisoned and trying to unite with her Lord, receives a visit from Hanuman, the Guru or divine teacher, who shows her the Lord’s ring, which is Brahma-Jnana, the supreme wisdom that destroys all illusions; and thus Sita finds the way to be one with Shri Rama, or, in other words, the Jivatman finds itself one with the Paramatman[10].

Tulsi’s Works[edit]

The works of Tulsidas are about Sri Ram, with two exceptions: Krishna-gitavali and Parvati-mangal. Tulsidas’s magnum opus, the Ramcharitmanas, is the story of Sri Ram retold in mellifluous language—an outburst of bhakti based on his own spiritual experiences. Although the origin of the Ramcharitmanas lies in the Valmiki Ramayana, its immediate source is the Adhyatma Ramayana. What are the differences between these two Ramayanas? The Valmiki Ramayana is ancient, has 24,000 verses, and depicts Rama as the epitome of ‘human’ perfection. The much shorter Adhyatma Ramayana, a part of the Brahmanda Purana, is of a later period. It depicts Rama as Brahman itself, and is an excellent confluence of Advaita Vedanta philosophy and the Valmiki Ramayana. The character Ravana in the Valmiki Ramayana is a plain villain, symbolic of vice in an ordinary human being. By contrast, the Ravana of the Adhyatma Ramayana longs for liberation through confrontation with Rama, which is described as vidvesha bhakti. [11]

‘Ramcharitmanas’ means ‘the lake of the deeds of Ram’. The entire story is a narration by Shiv to Parvati. ‘Manas’ here denotes a lake conceived in the mind of Shiv. Like the other Ramayanas, the Ramcharitmanas also contains seven kandas. On literary merit, it can be compared with the Sanskrit works of Kalidasa. According to Vishwanath, Tulsidas has packed into this single work all the drama and variety of emotions, moods, and judgements that Shakespeare spread out across his thirty-seven plays. [12] In addition, he depicts how one ‘ought to be’. It is written in Awadhi, or Baiswari—the dialect of the Awadh region—mainly in the chaupai and doha metres, and is sung to a sweet and captivating tune. It not only provides a philosophical outlook on life through its enthralling poetry, but is also a powerful tool for lila chintan, or thinking of the exploits and glories of God, which is an efficacious method of sadhana.

Tulsidas’s other long works include the following:

- Dohavali, written in Brajbhasha and containing 573 verses in the Doha and Soratha metres. A variety of subjects are dealt with in this work, including religion, bhakti, ethics, love, discrimination, the nature of saints, and the glory of Sri Ram and the name of God.

- Kavitta Ramayana, or Kavitavali, containing the story of Sri Ram in 369 stanzas in the Kavitta, Savaiya, Chhapyaya, Jhulana, and some other metres. It is very popular owing to its style and disposition. It describes the majestic side of Sri Ram.

- Gitavali, a collection of 330 songs set to different ragas—Kedara, Soratha, Lalita, Chanchari, and others—where the depth of mood is brought to the fore in preference to philosophy. It portrays the tender aspect of Sri Ram.

- Vinay-patrika, with 279 hymns and prayers, is a book of petitions in the court of King Ram.

- Krishnavali, or Krishna-gitavali, has 61 songs on Sri Krishna. [13]

The following are his shorter works:

- Vairagyasandipini, which deals with the nature of dispassion

- Ramlala-nahachu, verses for nahachu, a ritual performed at the time of yajnopavita, sacred-thread ceremony, and marriage

- Ramajna-prashna, verses for an auspicious beginning to a journey or a task

- Barvai Ramayan, a small poetic composition in the Barvai metre

- Janki-mangal and Parvati-mangal, which describe the marriages of Sita and Parvati

- Hanuman Bahuk, an appendix to Kavitavali containing prayers to Hanuman; and Hanuman-chalisa, forty rhymes in praise of Hanuman.

Tulsi’s Philosophy[edit]

Tulsidas was ardently devoted to Sri Ram; in his works, Sri Ram functions as a symbol on which the human mind can focus for the double purpose of conceiving the ultimate Reality and expressing devotion to it. Thus, Tulsi’s Ram is not a historical human character, but Satchidananda, which has not even an iota of the darkness of delusion’ [14]

This is the reason why other deities such as Krishna and Shiv appear in his works—rather interchangeably—in addition to Ram. Through his own purity and devotion, Tulsidas brought the impersonal, attributeless Brahman within the range of the imagination of common people and into their daily lives. He brought the Supreme, propounded by Sri Shankaracharya as the unknowable Brahman, within the reach of the masses. He made the Formless take birth and walk on earth and thus redirected the flow of people’s consciousness to this lofty ideal.

How could the formless Brahman become a human being? This abstract and ever-perplexing metaphysical question is clarified in the first canto of the Ramcharitmanas, through a conversation between Parvati and Shiv:

Parvati: Is this that Ram, the son of Ayodhya’s king or is he an unborn, attributeless, and unperceivable being? If he is the son of a king, how can he be Brahman? (If he is Brahman) how did he get perturbed upon the loss of his wife? [15]. Shiv: There is no difference between the saguna, endowed with attributes, and the nirguna, attributeless. … That which is attributeless, formless, unmanifested, and unborn, is none other than the saguna, just as ice is nothing but water. Sri Ram is the all-pervasive Brahman, the supreme Bliss, the Almighty, the Ancient[16].

While Sri Ram is the omnipresent, omnipotent, omniscient Brahman, the jiva is ‘a part of Ishvara— indestructible, conscious, unblemished, and blissful by its very nature. Being under the control of maya, the jiva is tied up, like a parrot or a monkey! And in this way, a knot has been formed between consciousness and matter, which is very difficult to untie, although unreal’ [17].

Tulsidas enlightens the miserable, struggling, and floundering jiva thus:

Union, disunion; experience—pleasant and unpleasant; friend, foe, and the neutral; all these are snares of delusion. Birth and death; provision and deprivation; action and time; are all the meshes of the world. Land and city; wealth, home, and family; heaven and hell; as much be the sensible world, all that is seen, heard, thought—the root of all this is in delusion. In reality, they are not (there)[18].

Further, if in a dream, a king becomes a beggar, or a pauper the king Indra of heaven, is there any gain or loss upon waking up? In a similar manner, one should perceive the phenomenal world. Thinking thus, one should not get into the trammels of anger, and should not blame others. Everyone is asleep due to the influence of moha, delusion, and is dreaming various dreams [19].

Sri Ram is Brahman itself. He is unknowable, unperceivable, beginningless, nonpareil, devoid of transformation, and indivisible. He is that which the Vedas have been describing as ‘neti-neti, not this, not this’ [20].

About maya, the cause of bondage, Tulsidas writes:

Me and mine, you and yours—this is maya, which has captivated all jivas. The senses and their objects, and that up to which the mind can reach, O brother, know all that to be maya. But this maya is of two kinds: one is vidya, the other avidya. Hear further the difference: One (avidya) is evil and highly painful, due to whose control the jiva has fallen into the pit of samsara. The other (vidya) has in her control the virtues which orchestrate the universe; however, it is prompted by the Lord Himself—in it is not its own power [21].

Tulsidas urges us to repeat the name of God, because it is Ram’s name that redeems, and not Sri Ram himself: ‘Sri Ram redeemed only Shabari, Jatayu, and others, but the Name of Sri Ram itself has raised sinners, countless in number’ [22]. ‘Ram Ram ramu, Ram Ram ratu; repeat and savour the Name’; [23] ‘ram-nam japu; repeat Ram’s name’ [24] . Tulsidas even says: ‘Let my skin be used to make the shoes of the one who utters the word “Ram” even by mistake.’ [25]

Tulsidas has advised us to be firm in the journey to our goal. Swami Vivekananda, quoting Tulsidas, says: ‘The elephant walks the market-place and a thousand curs bark at him; so the Sadhus have no ill-feeling if worldly people slander them.’ [26] And ‘take the sweetness of all, sit with all, take the name of all, say yea, yea, but keep your seat firm’ [27].

Tulsi’s Importance[edit]

What is the importance of the bhakti movement in general and of Tulsidas in particular? Through his works, Tulsidas set in train some important effects, pertinent to his time, without which Indian society would probably have gone into darker times. Tulsidas’s influence can be recognized in four distinct areas:

Counteracting Occultism[edit]

At that time there were four major secretive cults that cultivated the practice of supernatural powers: the Vedic sacrificial, the Tantric, the Natha, and the Mahanubhava. It is natural that common people will equate religion with occultism.

Tulsidas’s teachings bailed out religion from this pitfall and made it plain and simple. He emphasized living a virtuous life and developing human perfection, as opposed to supernatural achievement.

Opposition to Left-hand Practices[edit]

With his devotion and teachings, Tulsidas provided an alternative to the cults that showed a proclivity for debauchery. Shakta cults used to practise the rite of chakra-puja, in which an equal number of men and women sit round in a circle and partake of the five ‘m’s: madya (wine), mamsa (meat), matsya (fish), mudra (cereals) and maithuna (sexual union). The Shaiva cults of the kapalikas and kalamukhas also followed licentious rituals and practices. The ideal of illicit love between Krishna and Radha might also have been reduced to immoral practices in the hands of unfit and incompetent persons, had an alternative not been provided. The reason for this downfall is that the inherently weak and indecisive human mind easily and unconsciously slips into permissive practices and is consumed by them. As opposed to this, Tulsidas placed before the people the ideal of chaste grihastha life.

Introduction of an Ideal to Emulate[edit]

A person directly described as a superhuman deity would surely fail to be a model for human beings to emulate—in such a case, people would ‘worship’ him rather than emulate him! Tulsidas presented a picture of human perfection, achievable by common people, through which one could uplift and divinize one’s own character.

Tulsidas never became attracted to miracles or money. He was guileless but fearless and frank, innocent but outspoken and plain in speech. He did not preach any particularized doctrine, nor did he found a sect or school. Yet his pure life and enchanting, forceful, and touching poetry have cast a permanent spell on society.

References[edit]

- ↑ See Mataprasad Gupta, Tulsidas (Allahabad: Lokabharati), 52–141, and Ramcharitmanas, 1.31.6.

- ↑ The Cultural Heritage of India, 6 vols (Kolkata: Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, 2001), 4.379

- ↑ Goswami Tulsidas, Vinay-patrika, 76.1.

- ↑ For example, Ramcharitmanas, 3.4.1–12, 3.11.2–8, 7.108.1–9 and passim; Vinay-patrika, 10–12, 50, 56– 60.

- ↑ Ramji Tiwari, Goswami Tulsidas (New Delhi: Sahitya Academy, 2007), 11.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, ed. James Hastings and John A Selbie (Montana: Kessinger, 2003), 12.472.

- ↑ Vinay-patrika, 120.1.

- ↑ Rajapati Dikshit, Tulsidas aur Unka Yug (Varanasi:Jnanamandal, 1975), 16. 9. The Cultural Heritage of India, 4.395.

- ↑ The Cultural Heritage of India, 4.395.

- ↑ The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, 9 vols (Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 1–8, 1989; 9, 1997), 5.415.

- ↑ For a detailed discussion on the differences between the two Ramayanas, see Adhyātma Rāmāyana, trans. Swami Tapasyananda (Madras: Ramakrishna Math, 1985), 369–76.

- ↑ Tulsidasa’s Shri Ramacharitamanasa, trans. R C Prasad (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1994), 722.

- ↑ Goswāmī Tulasīdāsa, 27–52

- ↑ Ramcharitmanas, 1.116.3.

- ↑ Ramcharitmanas, 1.108.4, 1.109.1

- ↑ Ramcharitmanas 1.116.1-4

- ↑ Ramcharitmanas 7.117.1–2

- ↑ Ramcharitmanas 2.92.3–4

- ↑ Ramcharitmanas 2.92, 2.93.1

- ↑ Ramcharitmanas 2.93.4

- ↑ Ramcharitmanas 3.14.1–3

- ↑ Ramcharitmanas 1.24

- ↑ Vinay-patrika, 65.1.

- ↑ Barvai Ramayan, 48 and passim; Vairagya-sandipani,4 and 40.

- ↑ Vairagya-sandipani, 37.

- ↑ Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, 7.135.

- ↑ Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda 3.64