Meditation and Reflection on the divine play

By Swami Atmajanananda

One of the greatest opportunities and blessings in the life of a devotee is to reflect on the divine play of God and to let that reflection deepen into meditation. This practice not only brings immense joy, but also helps deepen one’s spiritual life and transform one’s nature. And it requires no great learning, study of the scriptures, or powers of mental control. But once we get a taste for this practice, we find that it grows more and more intense, and we discover that a whole new dimension has been added to our spiritual lives and practice.

In order to fully appreciate its wonderful power of attraction and purification of the mind and heart, it will be helpful to examine the three basic components of lila chintana and lila dhyana. As with all aspects of spiritual life, many of the concepts and ideas are deceptively simple. And while we are all familiar with the ideas of reflection, meditation and lila, we find that the type of meditation and reflection we engage in this particular practice is very much coloured by the concept of lila, and thus will be quite different from the types of meditation and reflection we practise when following the paths of yoga and knowledge.

Lila[edit]

The term lila has three basic meanings, each distinct in some sense, yet closely related. It may refer to

- a play, sport, pastime, a diversion or amusement. It also conveys the meaning of

- ease or facility, something that is ‘mere child’s play’. And finally, it gives the sense that

- something is not entirely real: it may be a mere appearance, a semblance, pretense, disguise, or sham, and may even convey the meaning of a kind of joke (one not always funny to those not in the know).

The term lila may be used in various contexts and with different layers of meaning, but in each and every case it refers to a kind of manifestation (real or otherwise, depending on the context). It is an idea based on the belief that God, or Brahman, is not merely a transcendent, unmanifest reality, but is also immanent, and manifests in a variety of different ways.

Sri Ramakrishna was very fond of this idea of lila as the manifestation of the divine in the relative world, and he often juxtaposed it with the idea of nitya, the eternal, unmanifest, absolute aspect of God. While he recognized that God manifests in numberless ways, for him the highest and greatest manifestation of God was in the human form. He says "Since my arm was injured, a deep change has come over me. I now delight only in the Naralīlā, the human manifestation of God. Nitya and Līlā. The Nitya is the Indivisible Satchidānanda, and the Līlā, or Sport, takes various forms, such as the Līlā as God, the Līlā as the deities, the Līlā as man, and the Līlā as the universe. Vaisnavcharan used to say that one has attained Perfect Knowledge if one believes in God sporting as man. I wouldn’t admit it then. But now I realize that he was right."[1].

From this point of view, it may be understood that Brahman’s manifestation as the different deities, as the visible universe, as all living beings, even as the Personal God, is all a kind of play, not real in any absolute sense and not explainable in any rational way. It is said to be all just for fun, since Brahman cannot feel any need to manifest or any lack if there is no so-called creation. If Brahman is to be considered perfect, there can be no room for any desire, and so we end up with the concept of lila.

Two Aspects of Nara-lila[edit]

But even from the point of view of nara-lila, God manifested in human form, there appear to be two distinct ideas. From a philosophical and non-dualistic point of view, it is Brahman alone which manifests in the form of all human beings. Due to the force of maya, Brahman has forgotten its true nature, whilst being caught up in the drama of life. That is why even quarrels between one person and another, battles between one nation and another, have the quality of play to the God-realized soul. For it is God himself who is the actor, playing each and every role, in this divine and seemingly mad play of life. We find Sri Ramakrishna often in this mood, especially toward the end of his life, looking upon the body as a mere pillow case and seeing only God within, playing the role of all beings.

But there is a second sense of nara-lila, which is more consistent with a devotional attitude and with dualistic spiritual practices (though it may also, as Sri Ramakrishna says, lead to the knowledge of Brahman). This second sense revolves around the concept of the avatara, or divine incarnation. It is typically this idea that we refer to when we speak of meditation and reflection on the human lila of God.

As described above, one aspect of God’s sport as man is that He manifests as all living beings, or at the very least, dwells within the hearts of all living beings as the higher Self. But the devotional schools maintain that in addition to this, there is a special kind of manifestation that takes place from time to time, perhaps necessitated by some extraordinary historical or social conditions. At such times, an eternally perfect soul, which is somehow one with the Personal God, descends to earth and assumes a human body. And that soul does not simply come alone, but brings along its own shakti, in the form of a consort, and also a handful of divine companions. This is a belief typically associated with the worshipers of Krishna, and to a somewhat lesser extent, Rama.

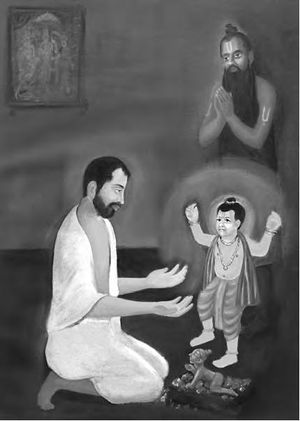

There is a belief among certain Vaishnavas that the divine sport between Krishna and the gopis takes place eternally in an eternal Vrindavan, a divine sphere not of this world. But they also believe that such play takes place on earth in every cycle. Here the idea of lila is especially pronounced, as Krishna is himself quite a practical prankster and fond of play and sport. And we find that each stage of Krishna’s life is considered another opportunity to contemplate his divine nature and divine play: as a small baby, as a young boy frolicking with the cow-herd boys and milkmaid girls, and even as the young prince of Mathura and charioteer of Arjuna.

Meditation[edit]

The practice of meditation can also be applied to this idea of lila. The main elements of meditation as taught in the yoga tradition are well known. A person tries to withdraw the mind from contact with external objects by closing the senses. Then he attempts to focus his mind on a single point or object of meditation and tries to keep the mind centered on that one point. When the mind begins to stray from that object, as it naturally does, he tries to bring it back through the process of abhyasa yoga, repeated practice, until it becomes trained to remained fixed on the Chosen Ideal, the object of meditation.

As an example of this one-pointedness (ekagrata), Sri Ramakrishna mentions Arjuna and his practice of archery. At the time of aiming at a bird, Drona asks Arjuna, ‘What do you see? Do you see these kings?’ ‘No, sir.’, Arjun replies. Then he asks Arjun, ‘Do you see me?’ ‘No.’, replies Arjun. ‘The trees?’ ‘No.’ ‘The bird on the tree?’ ‘No.’ ‘What then do you see?’ ‘Only the eye of the bird.’

But attaining this same kind of one-pointedness in meditation is far more difficult, especially in the beginning. The same Arjuna who was so adept at blocking out everything else and focusing wholly on his objective when it came to archery, found the control of his mind to be as difficult as trying to control the wind—‘tasyāham nigraham manye vayoriva suduskaram’ [2]. The mind rebels, doesn’t like to remain quiet, and likes to run around. And when it loses contact with its objective, it may end up going anywhere. So if one's concentration is only on the ‘eye of the bird’, there is every possibility that when the mind strays, it will lose not only the eye but the bird as well. And then one's whole meditation is spoiled till one regains his focus.

This is precisely why meditation on the divine play of an incarnation of God or a great saint can be beneficial. It allows a person to keep his focus on a single point, just as in the yogic type of meditation. However that single point has many aspects to it, like a gem. And when the mind wanders away from one aspect, rather than getting lost altogether, it can simply rest on another one of the infinite divine aspects. So the tendency of the mind to wander no longer represents a liability for the devotee, but instead becomes a positive aid in this kind of meditation. One divine association to lead the mind to another, so that it always remains within the circle of the divine presence, just as the tether of a cow allows it to graze within a certain area defined by the length of the rope.

Suppose, for example, one wants to meditate on the image of Sri Ramakrishna. As one enters into the chamber of the heart, he finds himself standing in Sri Ramakrishna’s room in Dakshineswar. He pictures him seated on the small cot next to the larger Rakhal, Latu, Baburam, and the others seated before him on the floor. He lets his eyes wander across the room and sees the holy pictures on the wall. And the image of Sri Ramakrishna awaking in the morning and saluting each of the pictures, clapping his hands and repeating the various names of God, flashes before his eyes. He hears Narendra singing in his beautiful voice, throwing Sri Ramakrishna into an ecstatic mood, who then rises from his seat and begins to dance. The devotees form a circle around him and also dance. Then he becomes motionless in samadhi, Baburam quickly coming to his side to see that he does not fall.

In the northeast corner of the room, where the large container of Ganges water sits, he is reminded of that blessed night of Phalaharini Kali Puja, when Sri Ramakrishna worshiped Sri Sarada Devi as Shodashi, and both the worshiper and the worshiped become lost in samadhi and pass the night in that state.

Or if the mind is not content to remain within the confines of Sri Ramakrishna’s room, it can accompany him to the Kali temple, and watch him sit before the image of Mother Kali, sing songs to her, wave the chamara before her, and enter into a state of divine inebriation. Or it can stroll to the north of Sri Ramakrishna’s room to the Nahabat, where Sri Sarada Devi is absorbed in the worship of Sri Ramakrishna, or standing behind the bamboo screen watching the divine scenes taking place in his room. There is no end to the different ways in which one can enjoy the divine sport and company of Sri Ramakrishna through the power of imagination and the practice of lila dhyana.

Advantages of Lila Dhyana[edit]

There are several advantages to this kind of meditation. First, it allows one to transform the faculty of imagination from an obstacle to concentration to an aid. The very same tendency of the mind to wander which gets one into so much trouble in other types of meditation becomes a positive help here. And by giving the imagination certain limits within which to work, we find that the mind does not wander to other things, such as one's job, relationships, family, or friends. A second advantage is that one can practice this type of meditation even if he lacks the perfect control over the mind that is necessary in the path of raja yoga. We also find that this type of meditation counteracts some of the obstacles often encountered in meditation, especially the feeling of boredom that may sometimes come or the tendency of the mind to fall prey to drowsiness.

One of the ironies of lila dhyana is that, although one may take up the practice because he feels unable to concentrate the mind in any one-pointed sense on a Chosen Ideal, his ability to focus his mind actually increases through this practice and he eventually reaches a point where the mind does get fixed on the object of meditation. When he feels his mind gathering itself together, he can simply imagine the kirtan coming to an end, Sri Ramakrishna being slowly helped back to his cot, and again going into a deep state of samadhi, just as he is seen to be in his photograph. Then the devotee can resume his seat before him and simply gaze at the blissful image of Sri Ramakrishna in ecstasy. And like Arjuna, he has entered the state of focusing only on the eye of the bird, and not noticing the surroundings or anyone else in the room or even himself.

Fruits of Lila Dhyana[edit]

The first thing one notices after practicing this kind of meditation is that there is a great deal of joy in it. That is because one feels his Chosen Ideal to be alive and present before him, and seated there alongside of him. The devotee has, in a sense, crossed time and space, and experienced the joy of the direct presence of his Chosen Ideal, all with the aid of the imagination. This type of experience, though far from being any kind of spiritual experience, nevertheless has a great power to transform one's way of thinking and feeling. The connection and relationship with the Chosen Ideal becomes something concrete and tangible. That Ideal is felt to be one's very own, in whatever relationship it is cherished —as a friend, child, father, mother, or master—and one's feeling of love and devotion grows in proportion as this feeling of closeness intensifies.

Furthermore, as one identifies with the imagined body of oneself seated before the Chosen Ideal in the chamber of one's heart, at the close of our meditation, one finds that he had unknowingly dis-identified himself from the physical body of the waking state. So, one of the consequences of this kind of meditation is that a person's identification and attachment to the body is attenuated. He also realizes that while he was dwelling in the presence of the Chosen Ideal at the time of meditation, in a completely different realm of time and space, he had become oblivious to his own surroundings. He had, for a few precious moments, completely forgotten the world of his ordinary state of consciousness and had entered into the world of the divine play.

From a philosophical point of view, the devotee also comes to realize that all of the elements of his meditation exist in the ethereal realm of pure consciousness and are composed of pure consciousness. Sri Ramakrishna often used to speak of chinmaya shyama and chinmaya dhama, both the Lord and his abode being embodiments of pure consciousness. And it applies equally to the image of the Chosen Ideal in this kind of lila dhyana, as well as to the surroundings — Sri Ramakrishna’s room at Dakshineswar, Sri Ramakrishna himself, and all of the devotees, including oneself. He gets a sense of the oneness of his Chosen Ideal with the infinite Brahman, a sense of the reality and limitlessness of the inner world of his own consciousness and a sense of the hazy, transitory nature of the external world.

This type of meditation has a tremendous power to transform a person in another way as well. Since the devotee meditates not only on the image of his Chosen Ideal in lila dhyana, but also on the personality and qualities, a kind of transference takes place wherein he begins to take on the qualities of his Chosen Ideal. As he thinks of Sri Ramakrishna and pictures him showering his love and affection on the devotees, he cannot help but imbibe some of those same qualities of love. And as he pictures him going into states of divine ecstasy and inebriation at the very mention of God, he cannot help but acquire a bit of longing for that same kind of God-realization.

And finally, there is a great deal of carry-over effect with this kind of meditation, so that a portion of the mind continues to dwell in the presence of the Chosen Ideal at all times—at Dakshineswar with Sri Ramakrishna or perhaps with Sri SaradaDevi, the Holy Mother, at Jayrambati—and one feels an unexpected bliss bubble up from time to time when these thoughts rise to the surface of the mind. In this way, a kind of natural and spontaneous recollection of the Chosen Ideal and the divine play goes on in one's mind at all times. And this brings him to the final component of this topic, lila chintana, reflection on the divine sport of the Lord.

Lila Chintana[edit]

Through regular meditation, a kind of natural remembrance and recollection of one's Chosen Ideal takes place, which again is reinforced by further meditation. This is one of the greatest aids in spiritual life. It is of such importance that both Sri Ramakrishna and the Holy Mother often said that it is enough if one can practise these two things, constant remembrance of and reflection on God (smarana and manana). But it is equally true that a person's meditation depends on an active and intentional effort to remember his Chosen Ideal throughout the day. And one of the best ways to do this is to practice lila chintana, reflection on the divine sport of the Lord. While there are many ways to pursue this goal, there are two specific aids that are especially helpful: spiritual reading and pilgrimage.

Many spiritual traditions have a specific literature dealing with the divine play of God. For Vaishnavas, it is the Bhagavata Purana and similar texts, filled with stories of the divine play of Sri Krishna. Followers of Sri Ramakrishna and Sri Sarada Devi have the special benefit of accurately recorded conversations between them and their disciples and devotees. The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, in particular, for not only are Sri Ramakrishna’s words faithfully taken down by his disciple Mahendranath Gupta, but also detailed descriptions of where he was sitting at the time, the direction he was facing, who was in his presence and each and every possible detail, including the phase of the moon are also recorded.

This type of literature calls for its own particular kind of reading. The Gospels of Sri Ramakrishna and the Holy Mother are meant for daily and repeated reading, and as one continues to read them, the more enlightened he becomes. While reading them, the mind can contemplate on the time and place of their origin and can picture the exact incident that is described. In this way, reading becomes an intense kind of contemplation bordering on meditation. The devotee becomes filled with their spirit, infused with the joy that emanates from their words, and he feels the living presence of Sri Ramakrishna and the Holy Mother.

In addition to a regular habit of daily reading, there is another technique that is very helpful for meditation. That is to read a particular passage, and use the incidents or teachings described there as the subject of one's meditation. For example, while reading about Sri Ramakrishna’s visit to Balaram Basu’s house during the Ratha Yatra festival, one may picture himself on the inner veranda with him as he pulls the chariot. Or while reading about the Holy Mother sitting in the kitchen in her home in Jayrambati, dressing vegetables and talking to her beloved young disciples from Koalpara, one can imagine himself to be among them. The result of both of these approaches to the literature surrounding Sri Ramakrishna and Sri Sarada Devi is twofold: on the one hand, the devotee finds that his mind easily flies to the presence of Sri Ramakrishna and Sri Sarada Devi in his meditation, causing him to feel himself seated before them; and on the other, he gets a tangible experience of the reality of the divine lila at all times and feels that he can experience the joy of sitting in their presence at any time through the practice of contemplation.

The second great aid to reflection on the divine lila is to actually go and visit the places associated with the earthly play of a divine incarnation. And it is important not only to visit these sacred places—Dakshineswar, Kamarpukur, Kashipur, Jayrambati, and Baghbazar, among others—but to take in the spiritual atmosphere, to contemplate the divine play that took place there, to picture the events that occurred and all the actors in that divine drama who played their different roles. The more one can burn the images of these holy places in his heart and mind, the easier it will be to return to them in his meditation and contemplation.

This type of meditation and reflection on the divine play of the Lord may not be for everyone. Some may prefer a more impersonal and philosophical kind of practice. But if one feels drawn to this kind of spiritual discipline and can practice it with great devotion and faith, a special kind of joy will come to him and he will feel that a new and precious dimension has been added to his spiritual life.

References[edit]

- ↑ Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, 24 February, 1884

- ↑ Bhagavad Gita, 6.3

- Originally published as "The Śākta Contemplative Tradition" by Prabhuddha Bharata January 2007 edition

. Reprinted with permission.