Buddhism is also known as Bauddh Dharm, Buddha Dharm, Buddhaśāsana, Buddhavachanam, Akāliko Dharm, Arya Aśtānga Dharm, and Ariyassa Dhammavinayo.

The word 'Buddha' has been used not just in the Buddhist context, but also for arihants in Jain Dharm, for Ganesh, Shiva[1] and others.

Gautama Buddha’s and his predecessor-Buddhas' teachings of four noble truths and eight-fold noble paths form a religion called as Buddhism. Buddhists are known historically as Bauddh, , Buddhadasa, Saugāta, Muktakachhas, Murdhabhishikta, Munigana (in southern India), Raktapata, Śākya, Śākyaputto, Śākyabhiksu, Āriyasavako[2], and Jinaputto[3].

While competition existed among the clergy Buddhism and tirthikas, there were also clerics of it and other sects that declared being Buddhist or worshiping Buddha isn't any different than being a member of a different sect. "Buddha tungal lawan Siva" or "Buddha is one with Siva" is declared.[4] The 14th century Indonesian poem Sutasoma declares, "They are indeed different, yet how is it possible to recognize their difference in a glance, since the truth of Jina (Buddha) and the truth of Shiva is one. They are indeed different, but they are of the same kind, as there is no duality in Truth.”[5]

Noble Truths & Paths[edit]

These four noble truths are:

- Dukha - It refers to the existence of suffering in the world.

- Dukha-samudhaya - It refers to the cause for suffering.

- Dukhanirodha - It refers that it is possible to stop suffering.

- Dukha-nirodha marga - It refers to the ways out of the suffering.

The eight-fold noble paths are:

- Samyak-drsti - It means right views.

- Samyak-sankalpa - It means right resolve.

- Samyak-karmanta - It means right conduct.

- Samyagjiva - It means right livelihood.

- Samyag-vyayama - It means right effort.

- Samyak-smrti - It means right mindfulness.

- Samyak-samadhi - It means right concentration.

So "the kinship of the religions of the country stems from the fact that Jains, Buddhists and Sikhs look back to Hinduism as their common mother."[6]

Brahman in Buddhism[edit]

- See also: Brahman

Brahma as perfection[edit]

It has been hard to determine whether the Buddha's philosophy is atheistic, non-theistic or that it indeed does emphasize on the unity with Brahman like mainstream Hinduism does. Examining Buddhist scriptures and deciphering between the words Brāhma (e.g., Brahman) and Brahmā[7] has been hard. Referring to differentiation them, Buddhist scholar B. R. Barua says, "The cases where the Absolute is clearly meant ought to be carefully distinguished from others where Brahma is referred".[8]

While "Brahmā" in Buddhist scripture, like Vedic scriptures, also refers to the non-eternal demigod, "Brāhma" (Brāhman) is believed by scholars to refer to the eternal perfect being, and the highest stage any person can achieve is labelled as Brahmā. For example in addition to Buddha's Dharm being called "Astānga Mārga"[9] and Dharmayāna, it is also addressed "Brahmayāna" because the aim is to lead one to perfection of Nirvana. As the Samyutta Nikaya says, V, 5-6, "This Aryan eight-fold Way may be spoken of as Brahmayāna or as Dhammayāna.[10] Again the Buddha Dharm is equated with Brahma when "...he has become dharm, he has become brāhman." It is said that the cultivation of compassion in its purest form is "called the divine life in this world (Brahman item viharam idhmahu)."[11]

In this context Brahmā is interpreted to mean divine. In the Suttanipata, 656, the Buddha says that he who has won the three-fold lore like self-denial, holy life and control and who will never be reborn is Brahmā.[12] Buddhism is compared to Brahmā in other scriptures like the Majjhima Nikaya[13] where the Dharmachakra of wheel of law is also called the Brahmāchakra.[14][15] The word Brahmachakra was nothing new and it was first mentioned in the Upaniṣads and it is believed the Buddha having received Vedic knowledge, used the term.[16] The Majjhima-Nikaya also says that the Buddha is 'Brahmapatta' or "one who has attained Brahman".[17], thus outlining that when Buddha became perfected by achieving Nirvana he also became Brahmā.

For the ultimate happiness of Nirvana, it is written that "one who has attained Nirvāṇa" it is said, "may justifiably employ theological terminology[18][19] As one attains Nirvaṇa they have the knowledge of enlightenment. So further, in Buddhist scriptures, "Brahmajala" refers to the best knowledge achieved.[20]

Later Buddhist scholars connect the state of Nirvāṇa with Brahman. Buddhaghoṣa in his Digha[21] says that the "Tathāgata or Buddha is dhammakaya brahmakaya dhammabhuta brahmabhuta."[22] This statement translates as, "For the Tathāgata is synonymous with dhamma and brahma and he who sees the dhamma sees the Buddha..."[23] Bhavaviveka uses the term Brahma-Abhyāsa, meaning "practicing Brahmā" which refers to the Buddhist trying to become one with Brahmā.[24]

Brahmacharya itself is a term used often to denote chastity and the way of the monk, both Śramana and Vedic. Buddha himself declared that the perfected religion he was preaching has always existed as a Brahma-faring path:

"Even so have I, monks, seen an ancient way, an ancient road followed by the wholly awakened ones of olden time....Along that have I done and the matters that I have come to know fully as I was going along it, I have told to the monks, nuns, men and women lay-followers, even monks, this Brahma-faring brahmacharya that is prosperous and flourishing, widespread and widely known become popular, well made manifest for gods and men."[25]

Like its sister-religion Jainism, Buddhism emphasizes that while one is in the state of Nirvāṇa, he is said to dwell in Brahman. A perfected human is said to "dwell in Brāhman".[26]

| English | Sanskrit |

|---|---|

|

|

Anatma[edit]

Shiva too has been addressed as 'anatma'. For example, in a Kashmiri scripture's verse there is an invocation to him as the Universal Soul (sarvatma) and selfless (anatma.)

Vedic interpretation in Buddhism[edit]

Buddhism does not deny that the Vedas in their true origin were sacred but it holds that they have been amended repeatedly by certain Brahmins to secure their positions in society. The Buddha declared that the Veda in its true form was declared by Kashyapa to certain ṛṣis, who by severe penances had acquired the power to see by divine eyes.[28] In the Buddhist Vinaya Pitaka of the Mahavagga[29][30] section the Buddha names these rishis, and declared the Vedic rishis "Atthako, Vâmako, Vâmadevo, Vessâmitto, Yamataggi, Angiraso, Bhâradvâjo, Vâsettho, Kassapo, and Bhagu"[31] but that it was altered by a few Brahmins who introduced animal sacrifices. The Vinaya Pitaka's section Anguttara Nikaya: Panchaka Nipata says that it was on this alteration of the true Veda that the Buddha refused to pay respect to the Vedas of his time.[32] By the practices of these ṛṣis severe austerities had acquired the power of seeing with divine eyes. They were:

- Attako - Ashtaka

- Vamako - Vamaka

- Vamadeo - Vamadeva

- Vessamitto - Viswamitra

- Yamataggi - Jamadagni

- Angiraso - Angirasa

- Bharaddwajo - Bharadwaj

- Vasseto - Vasishta

- Kassapo - Kasyapa

- Bhagu

Also in the "Brahmana Dhammika Sutta"[33][34] of the Suttanipata section of Vinaya Pitaka[35] there is a story of when the Buddha was in Jetavana village and there were a group of elderly Brahmin ascetics who sat down next to the Buddha and a conversation began.

- The elderly Brahmins asked him,

"Do the present Brahmans follow the same rules, practice the same rites as those in the more ancient times?"

- The Buddha replied,

"No."

- The elderly Brahmins asked the Buddha that if it were not inconvenient for him, that he would tell them of the Brahmana dharm of the previous generation.

- The Buddha replied:

So in this passage also the Buddha describes when the Brahmins were studying the Veda, the animal sacrifice customs had not yet began."There were formerly ṛṣis, men who had subdued all passion by the keeping of the sila precepts and the leading of a pure life...Their riches and possessions consisted in the study of the Veda and their treasure was a life free from all evil...The Brahmans, for a time, continued to do right and received in alms rice, seats, clothes, and oil, though they did not ask for them. The animals that were given they did not kill; but they procured useful medicaments from the cows, regarding them as friends and relatives, whose products give strength, beauty and health."

In the Mahāvagga,[36] the Buddha declares:

The one who annihilates the sins in himself, who is not proud, who is passionless, whose spirit is humble, who has comprehended the Vedas and is chaste, for whom no joy exists in the world, that one is lawfully called a brahman.

The Buddha was declared to have been born a Brahmin trained in the Vedas and its philosophies in a number of his previous lives according to Buddhist scriptures. Other Buddhas too were said to have been born as Brahmins that were trained in the Vedas.

The Mahāsupina Jātaka[37] and Lohakumbhi Jataka,[38] he declares that Brahmin Sariputra in a previous life was also a Brahmin that prevented animal sacrifice by declaring that animal sacrifice was actually against the Vedas.

Further, the Suttanipata 1000 declares that 32 mahāpuruṣa lakṣana[39] that Buddhism uses are declared in the Vedic mantras.[40] Brahmayu was a well-versed Vedic follower of the Buddha who by reading the four Vedas saw that the Buddha was auspicious as per his 32 symbols.[41]

Main Reasons for Buddhism's Decline in India[edit]

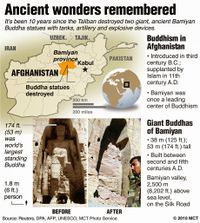

“In 871, coming from Balkh, Ya'kûb ravaged the Buddhist temples of Bamiyan before conquering Kabul and driving out the Turki Shahis. From then on, these territories, until then devoted to Buddhism, would gradually convert to Islam.” - Mustapha K. Chamakhi[42]

- Buddhism was mainly an ascetic religion

Buddhism had always been a monastic or ascetic religion with almost very few lay followers and so when Islamic people had invaded the Indian Subcontinent and persecuted all the Hindus,[43] due to the loss of Buddhist institutions such as their temples and universities, the outlawing of Hindu asceticism and the slaughter of Hindu clergy, they had no resources to continue their tradition and Buddhism waned.

- Militant Islam

The Taliban of Afghanistan destroying the Buddhist Bamiyan structures of ancient Afghanistan in the early 21st century is no different than how Islamists destroyed Buddhist structures.

Although Buddhism has received onslaught from militant Islam, Tibetan Buddhist scriptures predict a battle between Buddhism and Islam wherein Buddhism returns to and dominates Shambhala (Kashmir.) These descriptions can be found in the Kalachakra Tantra and the Vimalaprabha.[44] Tibetan Buddhist scriptures proclaim a 'mTha-'dMag' (Final War) wherein Dragpo Korlo-chan (Raudra Chakri) will combat kLa-klo-chos (Islam) and replace it with Buddhism.

As Buddhists were being persecuted by Muslim terrorists, the Sanatan societies of India gave them refuge. Dharmasvāmin the Tibetan pilgrim was bestowed with such from the Karnata Dynasty’s King Ramasimha of Mithila. Rahalasribhadra, the last Abbot of Nalanda, was supported by Jayadeva of Odantapuri. Melikian-Chirvani writes that the collapse of Buddhist kingdoms in eastern Iran led to a migration of Buddhists from there to Kashmir.[45] When Mongol ruler Mahmud Ghazan of Iran converted to Islam, he destroyed Buddhist centres and persecuted the religion, resulting in Buddhists in his dominion seeking refuge in Kashmir, Tibet and the rest of India.[46] In the mid-ninth century, there were migratory waves of Buddhist monks from Sind to Kathiawar.[47]

- Indians are non-sectarian

Because most Indians are non-sectarian, there was never been a staunch sect in India. Parents do not usually advocate a particular sect or worship in a stringent way. Children of Buddhist parents were always free to pursue any form of worship they wanted, just as the children of royal monarchs did so.

Some continued worship Buddha or practicing Buddhism, but the popularity of Bhakti Movement centered around Vaishnavism and Shaivism, and so the Indian masses gave Bhakti-yoga more importance than either Karma or Gyana yogas. For instance, the Sivatatavasaram speaks of the growing popularity of Shaivism and decline.

Several Buddhists also continued worshiping Buddha alongside other non-Buddhist gods and saints.

- Miscellaneous

Sri Moolavasam was the centre of Buddhism in southern India and due to sea level rises, it (like Krishna's Dwarka) submerged into the sea.

Self-Defence and Buddhism[edit]

Although Buddhists have historically, like Jains, practiced non-violence on an extreme level, not all Buddhist groups have believed this was a logical or ethical choice.

The pacifism of Buddhist communities led to them being ruled and then persecuted by Islamists in the medieval era and by communists [within China, North Korea, Tibet, and S.E. Asia] in the modern era.

In medieval and early modern Japan however, the Buddhist monks themselves were very practical. In a world plagued with warlords and bandits, they determined to help the innocent and to keep the peace within their territories. The monks who became ‘samurai’ (‘’warriors’’) were specifically known as ‘sohei’. They did not fight for wealth, land, women or glory, but simply to defend people and halt wars.

Buddhism not a Nastika doctrine[edit]

There were also Buddhists that were accused of believing in ideas outside of the Buddha's teachings, and they were called nastika in the "Bodhisattvabhumi" (a section of the Yogacarabhumi by Asanga) and the scripture also declared they should be subject to isolation so their views do not infect the rest of the Buddhist community.[48] Like the Manusmriti, the Bodhisattvabhumi also criticizes the nastika for reliance on logic only.[49]

Six major traditions of Buddhism[edit]

There are believed to be 6 specific oral traditions of Buddhism; The lineage from Tushita, the one from Nagaloka, from Uddiyana, from Bengal, from Bhetaka, and from Bhisokotacandana. Buddha Dipankara is said to have passed on teachings in all of these in disciplic succession right down to Gautama Buddha.[50]

Buddha paradises were locations on Earth[edit]

As Buddhism has been for most of its history a monastic religion, it had several heritages across the Indian Subcontinent. Each of the rural- and urban-commune ashrams headed by Buddhas were referred in Buddhist scriptures as a ‘Buddha-kshetra’. Buddhist scriptures acknowledge there were 5 principal ones, and each of them were at one point headed by one of the 5 Dhyani Buddhas.

- Akshobhya

- Amitabha

- Amogasiddhi

- Manjusri

- Ratnasambhava

The paradise of Amitabha, Sukhavati, is often spoken of as the best of these Buddha-kshetras. It is described as being in the west (i.e., western part of the Jambu-dvipa subcontinent.)

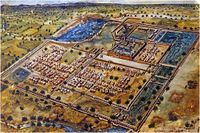

The exact location of it, based on the descriptions that are consistent with any Indian region, minus the mythology, is Dholavira (AKA Kotada Timba) on the island of Khadir-Bet in Gujarat state.

Dholavira was a major spiritual centre in the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), as noted by studies.

| Buddhist scripture | Archaeologists |

|---|---|

|

“And again, O Satiputra, that world Sukhavati is adorned with seven terraces, with seven rows of palm-trees, and with strings of bells.” |

A photo of the habitat of the Palm Tree.[1] |

| Buddhist scripture | Archaeologists |

|---|---|

|

“It is enclosed on every side, beautiful, brilliant with the four gems, gold, silver, beryl, and crystal.” |

“Today what is seen as a fortified quadrangular city set in harsh arid land, was once a thriving metropolis for 1200 years (3000 BCE-1800 BCE) and had an access to the sea prior to decrease in sea level.”[4] |

| Buddhist scripture | Archaeologists |

|---|---|

|

“Sukhavati is declared to be a large lake, the surface of which is covered with lotus-flowers (Padmas), red and white, with perfumes of rare odour.” |

“Archaeologists believe that the 5,000-year-old town must have been a lovely city of lakes in its heyday.”[5]

|

| Buddhist scripture | Archaeologists |

|---|---|

|

“Therefore it is named Sukhavati. Again, Sariputra, in the Sukhavati there is a lake of seven gems, flowing with the water of eight meritorious qualities; its bottom covered with pure golden sand; its four-sided banks and walks are composed of the precious gold , silver, lapislazuli, and crystal.” |

“Ornaments made in lapis lazuli, agate, carnelian, shells, silver and gold, as well as utensils and toys made from clay, also reveal a high artistic and technological sense.”

|

| Buddhist scripture | Archaeologists |

|---|---|

|

“There is no suffering in the Palace because within its walls lies Sukhavati, the There is a remarkable similarity between Land of Highest Happiness.” |

“The Dholavira citadel fortification wall was justifiably called a “monumental structure;” it enclosed the entire citadel mound.”

|

| Buddhist scripture | Archaeologists |

|---|---|

|

“Moreover Śāriputra, in this country there are always rare and wonderful varicoloured birds; white stork, peacocks, parrots, and egret, kalaviṅkas, and two-headed birds.” |

White Stork habitat map.[2] Egret habitat map.[3] [The region of Gujarat is the only place in western India what satisfies as a habitat for the mentioned birds] |

See also[edit]

- Buddhist patronage by Hindu kings

- Yungdrung Bon

- Jainism

- Sikhism

- Ethics of Hinduism

- Sanātan Dharm principle

References[edit]

- ↑ Svarnakarshana Bhairava Stotram; Shiva here is addressed "Namah Shuddhaya Buddhaya"

- ↑ P. 56 A Dictionary of the Pali Language By Robert Cæsar Childers

- ↑ P. 171 A Dictionary of the Pali Language By Robert Cæsar Childers

- ↑ P. 101 Proceedings - Punjab History Conference By Department of Punjab Historical Studies, Punjabi University

- ↑ Sutasoma By mPu Tantular

- ↑ Religions of the World S. Vernon McCasland, Grace E. Cairns, David C. Yu

- ↑ It means the demigod.

- ↑ P. 72 Dr. B.R. Barua Birth Centenary Commemoration Volume, 1989 by Hemendu Bikash Chowdhury, Beni Madhab Barua

- ↑ It means eight-fold path.

- ↑ P. 77 Elements of Buddhist iconography by Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy, Harvard-Yenching Institute

- ↑ P. 419 Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Buddhism by Samir Nath

- ↑ P. 121-122 The Buddha Image: Its Origin and Development By Yuvraj Krishan

- ↑ Majjhima Nikaya I.60

- ↑ It means wheel of Brahmā.

- ↑ P. 64 Indian horizons, Volume 1 by Indian Council for Cultural Relations

- ↑ P. 47 'Buddha and Buddhist Synods in India and Abroad' By Amarnath Thakur

- ↑ P. 5 Sri Venkateswara University Oriental Journal, Volume 18

- ↑ It means dhammena so Brahma-vadam vadeyya."

- ↑ P. 20 The philosophy of religion: a Buddhist perspective by Arvind Sharma

- ↑ P. 52 The Pacific world: journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies, Volume 5

- ↑ iii.8

- ↑ P. 262 Philosophy, grammar, and indology:essays in honour of Professor Gustav Roth

- ↑ P. 18 'Tradition and Modernity in Bhakti Movements' by Jayant Lele)

- ↑ P. 230 To See the Buddha: A Philosopher's Quest for the Meaning of Emptiness By Malcolm David Eckel

- ↑ P. 57 Buddhist Art & Antiquities of Himachal Pradesh, Upto 8th Century A.D. By Omacanda Hāṇḍā

- ↑ It means "brahmund saddhim samvasati" in sanskrit.

- ↑ P. 92 Chanting the names of Mañjuśrī : the Mañjuśrī-nāma-saṃgīti, Sanskrit and Tibetan texts By Alex Wayman

- ↑ P. 177 The sacred books of the Buddhists compared with history and modern science By Robert Spence Hardy

- ↑ Mahavagga I.245

- ↑ P. 494 The Pali-English dictionary By Thomas William Rhys Davids, William Stede

- ↑ P. 245 The Vinaya piṭakaṃ: one of the principle Buddhist holy scriptures ..., Volume 1 edited by Hermann Oldenberg

- ↑ P. 44 The legends and theories of the Buddhists, compared with history and science By Robert Spence Hardy; "...to certain ṛṣis.

- ↑ Brahmana Dhammika Sutta II,7

- ↑ P. 94 A history of Indian literature, Volume 2 by Moriz Winternitz

- ↑ P. 45-46 The legends and theories of the Buddhists, compared with history and science. By Robert Spence Hardy

- ↑ P. xxx, Pāli grammar: a phonetic and morphological sketch of the Pāli language, with an introductory essay on its form and character By Ivan Pavlovich Minaev

- ↑ P. 577 Dictionary of Pali Proper Names: Pali-English By G.P. Malalasekera

- ↑ P. 30 The Jataka or Stories of the Buddha's Former Births By E. B. Cowell

- ↑ These are the auspicious symbols of the Buddha.

- ↑ P. 121 The Buddha Image: Its Origin and Development By Yuvraj Krishan

- ↑ P. 371 Manual of Buddhism 1853 By R. Spence Hardy

- ↑ P. 75 “Islam in all its States” By Mustapha K. Chamakhi

- ↑ It includes Buddhists, Jains, Śaivas, etc

- ↑ P. 22 Proceedings of the Ninth Conference of the European Society for Central Asian Studies edited by Tomasz Gacek, Jadwiga Pstrusińska

- ↑ P. 86 Islam and Tibet – Interactions Along the Musk Routes By Anna Akasoy, Charles Burnett, Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim

- ↑ P. 350 Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World · Volume 1 By André Wink

- ↑ P. 116 Building Communities in Gujarāt: Architecture and Society During the Twelfth Through Fourteenth Centuries By Alka Patel

- ↑ P. 174 Unifying Hinduism: philosophy and identity in Indian intellectual history By Andrew J. Nicholson

- ↑ P. 174 Unifying Hinduism: philosophy and identity in Indian intellectual history By Andrew J. Nicholson

- ↑ P. 164 The Crystal Mirror of Philosophical Systems: A Tibetan Study of Asian By Thuken Losang Chokyi Nyima