Kanchipuram

By Dr Prema Nandakumar

Pushpeshu jati, purusheshu vishnu; Narishu rambha, nagareshu kanchi.

This jingle is attributed to Kalidasa, a connoisseur of places who might have seen enough of Kanchipuram more than a millennium ago to come up such a crisp verse. Certainly, for over two thousand years, Kanchipuram has been laying down layers of the finest in culture. Even though these earlier days have largely to be surmised, there is plenty of historical documentation about the Pallavas and Cholas, who had a big hand in building the city and its environs.

The original name of Kanchipuram was Kachchi Managar. There have been different interpretations of the word kanchi. The Sanskrit term denotes a woman’s waist-girdle. This place was also known as Tondaimandalam in ancient Sangam literature, in which it is referred to as a forest of kanchi (river portia) trees. The city itself is referred to as Kachchi in works like Manimekalai. It is located on the Palar River. The famous Sangam classic, Perumbanatruppadai, describes Kanchi and its king, Ilamtiraiyan thus:

Flanked by its belt of defensive jungles is that city

Whose doors are never closed to those who seek the prize.

Lovely like the pericarp of the many-petalled lotus /

The navel of the dark-hued Lord …[1]

Buddha Kanchi[edit]

Kanchipuram’s socio-religious presence is marked by a four-fold glory. Even today, people are drawn not to a monolith but a four-in-one city: the Buddha Kanchi, the Jina Kanchi, the Shiva Kanchi, and the Vishnu Kanchi. All of them have histories stretching back at least a couple of millennia, with the Buddhist faith being the earliest to have laid foundations at Kanchipuram.

According to the Girnar inscription of Emperor Ashoka, it is known that by the third century BCE, Buddhism had registered its presence widely in South India.[2]Some of the Tamil Sangam works like Natrinai and Madurai-k-kanji have references to Buddhism. For instance, the latter describes women going to a Buddhist vihara for worship:

Young women held fast to themselves

Little children ornamented with jewels

So they would not be lost; kissing them

And holding firmly their hands

That appeared like pollen-rich lotus buds,

They stood there, carrying flowers for worship,

And scented smoke, singing the glory

Of their Lord in that Buddha vihara …[3][4]

Significant parts of Manimekalai, a Buddhist epic from the later Sangam age, take place in Kanchipuram. Manimekalai is a dancer who later becomes a nun. She obtains the Amuda Surabhi (nectar vessel), which produces food without end. This she uses for performing charity. In the course of her travels, she is directed by her grandfather, Masattuvan, to go to Kanchi, as the city had been devastated by a drought. When she goes there, she finds a temple to Buddha at the very centre of the city:

The king builds a garden in honor of Manimekalai’s coming to help his people. Delighted, Manimekalai makes him build a lotus seat for Buddha. She then places the Amuda Surabhi on the lotus seat and welcomes all living beings to gather to be fed. It is an unforgettable scene in which all the marginalized, the hungry, the defeated, and the maimed come to her for succour:

Like life-giving sustenance for those who ate,

Like the result of giving alms to ascetics,

Like the yield when the seed is sown with thought

To water, earth, season, and work in the fields,

Like rains that fall to help the earth’s yield,

Was the maid compared and thanked by people

Whose hunger-sickness had been cured by her.

She then meets her spiritual teacher, Aravana Adikal, who instructs her in Dharma. Her mind illumined, Manimekalai dedicates herself to the ideal life that leads to salvation.

One realizes that the very ancient Buddhist past is very much present in today’s Kanchipuram when the author goes to Arappanancheri, where the sage Aravana is said to have spent the latter part of his life. Today the place is known as Arapperumchelvi Gramam (the place of the Maid of Great Charity). The author goes into the local temple, which had a huge pipal tree in front. Within was the goddess, Paranjoti Amman. The striking thing about this temple is a plaque proclaiming the following statement in Tamil: ‘From time immemorial, this village has not allowed sacrifice of any life.’ This plaque bears witness to the area having been Buddhist from early times.

History records the names of several great Buddhists of Kanchipuram who spread the Dharma all over the world. Buddhaghosha (fifth century CE), along with the monks Sumati and Jotipala, lived in Kanchi. Aniruddha, author of Abhidhammatthasangaha, lived in the Mulasoma Vihara. A Pallava king named Buddhavarman apparently built many viharas. Even today, one can walk across a Buddheri street. But one has to peer into unlit corners for vestiges of the Buddhist past. Buddhist statues on a pillar at the Kachabeshwara temple, pieces of what once was a stupa found in a field, and so on -- all point to the brilliance that had once adorned Kanchi.

Acharya Dharmapala, who entered the Sangha on the eve of his wedding, lived in Patatitta Vihara, built by Ashoka near Kanchipuram. He wrote Pali commentaries for some of the Tripitaka texts. He taught at Nalanda University but died young at the age of thirty-two. Ashoka’s closeness to Kanchi has been recorded by Hsuan Tsang, who says that a Buddhist stupa built by him was still standing four centuries later. Deepankara Tero, author of the Pali work Bhujja Madhu, lived in Balatissa Vihara in Kanchi. Ananda Tero of Kanchi was taken by Saddhamma Jotipala to Burma to spread Buddhism there. There are other revered names associated with Buddha Kanchi: Venudasa, Vajrabodhi, Sariputra … And among the most famous Buddhists of ancient Kanchi are Dignaga and Bodhidharma. Hsuan Tsang, who visited Kanchipuram in the seventh century CE, records that there were one hundred monasteries with ten thousand monks belonging to Teravada Buddhism following Dignaga’s yoga. Dignaga (fifth century CE) was a native of Kanchi and was born in Simhavaktra (Seeyaman-galam). His Hetuchakra (Wheel of Reason) inaugurated Buddhist philosophical logic. Bodhidharma (fifth century CE) was a Brahmana prince of Kanchi who became a Buddhist and was trained in the techniques of meditation by Prajnatara. He went to China during the Sung rule. Emperor Wu was not pleased with the manner in which Bodhidharma couched his answers. It is said the Indian monk shut himself up in a Shaolin temple in Honan Province and emerged after nine years with two books. One of them was the famous I Chin Ching.

Bodhidharma is considered the founding father of Zen Buddhism. Inspired by the Vajramushti technique prevalent in India, he taught martial arts to the Chinese (well known as the Shaolin martial arts) and also how to control the breath to strengthen the blood and immune system, energize the brain, and attain enlightenment. He is today revered by various names like Bodhitara, Ta-mo, and Bodhi Daruma. He passed away around 534 CE.

However, by the eleventh century, Buddhism was very much on the wane in Tamil land. Sectarian disputes and the decadence of Buddhist institutions brought this chapter to a close. As early as the seventh century, the Pallava king Mahendravarman issued a warning to the monks of Kanchipuram in his farce, Matta-vilasa-prahasana (Tale of the Drunken Monks). A religion that had established monasteries all over Tamil Nadu and an undeniably strong presence in the neighbouring Andhra country, one that had initiated a way of life that had percolated to the tiniest villages in the countryside, was reduced to a distant memory with dizzying speed.

So perhaps it is not surprising that no one in Kanchipuram could show where the Buddha Kanchi is, because there is none present. Other layers have been spread out over what was once a vast complex of Buddhism and Buddhist art and architecture. Wandering in search of artefacts, though, archeologists have not been disappointed. Some of the goddess sculptures in the Kamakshi temple have been identified as that of the Buddhist Tara Devi, and it was in this temple that a Buddhist stupa belonging to the second century BCE was discovered. T A Gopinatha Rao found a standing Buddha sculpture in the innermost corridor of the Kamakshi temple in 1915 (this has been subsequently shifted to the Madras Archaeological Museum). A Buddha sculpture unearthed near the Ekambreshwara temple is now kept in the adjacent police station. Flower and incense offerings indicate that the statue is held in veneration. It was also noteworthy to find that a devotee had applied an artistic circlet of sandal paste with kunkum to the Buddha’s forehead.

Even today, there are quite a few discoveries at hand to keep one inspired. In the Subarea Mudaliyar School ground, there is a massive Buddha seated in meditation, presiding over a class held in the open by the teacher, Hari Kumar. Buddhism has had a revival in these parts thanks to a social reformer, Ayoddhi Dasar, who sought to give voice to the underprivileged Dalits. On a visit to Koneripakkam to see a newly built shrine, Kannivel, a tour guide, showed the author around. The place was neat, and there were kolam decorations in front. At the entrance to the modest structure is a Buddha figure on a broken pillar. He was told it had been retrieved from a nearby place that was being dug up to build a Muslim dargah. The sanctum had a Buddha figure along with a bell, a cup of water, and a plate for ritual worship. Bodhidharma’s portrait, gifted by a devout Korean, looked down benevolently from the wall. A Buddha head in a glass case conveyed an amazing sense of peace. It had been found under an uprooted pipal tree. Kannivel told him that the entire space had once been a Buddhist monastery.

‘Should it always be “once upon a time” for Buddha in Kanchi?’ the author muses. Immediately the guide assured him that there is a shining future for Buddhism and led him to Bodhi Nagar. Near Vaiyavur Road and across a bit of slushy ground, they discovered a very clean and peaceful place. Entering it, he bowed at the flagstaff and walked a few steps to the Bodhi tree surrounded by a wall built in the Sanchi style. Founded by Ven. Divyananda, the Mahamuni Society is trying to return to the monastic style popularized by the Buddhists two millennia ago. In the shrine, there is a statue of Buddha sculpted in Mahabalipuram. The tranquil atmosphere took reminds one of the epic Manimekalai, and Sutamati’s prayer—

Our Lord, self-taught, the essence of faultless things,

Incarnating in nature’s several forms,

Always living for the good of others,

Never for himself: for the good of the world

His penance, with the idea of Dharma.

Hence his rolling the wheel of Dharma rays.

He won victory over desire; Buddha’s feet

Shall I praise, my tongue shall naught else do.

Jina Kanchi[edit]

If the Buddha Kanchi of yore cannot be pinpointed today, Jina Kanchi, fortunately, has to itself an allowed area where two temples have stood witness to the rise and fall of dynasties for over a millennium. Jainism seems to have come to Tamil Nadu even earlier than Buddhism because it is associated with Chandragupta Maurya’s retirement in Karnataka. It is widely believed that when his kingdom was devastated by a famine, Chandragupta renounced his throne on the advice of his spiritual preceptor, Bhadrabahu, and travelled to South India. Settling down in Karnataka, he is said to have taken to sallekhana (the Jain ascetic tradition of giving up one’s body by renouncing movement and eating). The work of master and disciple in furthering the cause of Jainism in South India must have been very deep indeed. The place where they stayed became the Shravanabelagola of later times, with the erection of the magnificent monolithic statue of Gomateshwara. Jainism spread rapidly and seems to have entered Kanchipuram not long after Chandragupta’s passing.

Though the age of Jainism in Tamil Nadu has not been preceisely determined, it does have a very ancient presence stretching back to the Sangam era. The monks belonging to the religion were known as samanas (from Sanskrit shramana) and the householders as savakas (or shravakas). Because the monks were an obvious visible presence as teachers, the pathway came to be known as the Samana religion. The monasteries were known as Samana palli (like the Buddhist vihara) and functioned as organized educational institutions. Kanchipuram, being the capital of the Tondaimandalam area (which once included Chennai, Tiruvellore, Vellore, and Tiruvannamalai) was not insulated from this sweep of Jainism all through South India.

The Pallava king Simhavishnu (seventh century), who ruled from Kanchipuram, was a follower of Vaishnavism, but he did not look down upon other religions. His son Mahendravarman was drawn to Jainism early in life. The wonderful cave temple at Sittannavasal is attributed to his munificence. Located in the Pudukottai area, the cave has frescoes on Jain spiritual themes like the Samavasarana (divine pavilion) Lake. It is significant that Mahendravarman’s drama, Matta-vilasa-prahasana, which is a satire on the ways of the Pashupatas, the Kapalikas, and the Buddhists, avoids any criticism of Vaishnavism, popular Shaivism, or Jainism.

Literature has kept alive some of Jainism’s old connections with Tondaimandalam. The author of the Jain epic Chulamani is associated with Karvetinagar near Tirupati. At a distance of ten miles from Kanchipuram is Tirupanambur, where the Jain acharya Akalanka lived. He is said to have defeated the Buddhists in a debate in the court of King Himasitala of Kanchi. The eminent Jain commentator Suranandi lived in Tiruparuttikunram. Merumandara Puranam is the legend of the two assistants of the thirteenth Tirthankara, Vimalanatha. This narrative in thirteen cantos about the princes Meru and Mandara is attributed to Mallisena Vamana (fourteenth century), who lived in Kanchipuram. The impressions of his feet and those of his disciple Pushpasena are honoured in the Chandraprabha temple at Tiruparuttikunram in Kanchi. Mallisena’s Purana upholds Jain thought with crystalline clarity:

If you wish to act, perform dharma.

If you wish to renounce, renounce anger.

If you wish to see, look at knowledge.

If you wish to guard, protect your vows.

Curiously, the work firmly states that women cannot achieve realization:

Mallisena has also written a commentary for the epic, Nilakesi. Udisi Devar, who authored Tirukkalampakam and Arungalacheppu, was the head of Arpakai village in Tondaimandalam. His Tirukkalampakam is an amazing attempt to take in the whole of the religious symbolism of his time and make them all represent the Arhat. He is Shiva, Brahma, Muruga (the lord who rested in the midst of the milky ocean), and even Shakti. Towards the end, Udisi Devar speaks in a voice which must have gone down well with the devotees, for already the Jain pantheon had a vast array of gods and goddesses:

Praising the beloved of the Lord,

The mother who gave birth to this earth,

Eternal Virgin, the goddess who sustained

Dharma; from her have blossomed forth

The six religions; the Self-create;

The one lamp illumining creation;

One who is an enemy to the disease of our birth;

The divine foster-mother who gives unstintingly

Her compassion to all living beings;

The chaste one who speaks in sublime accents;

A creeper of ananda; a flame of wisdom;

The medicine that cures the fever of the senses.

Thus do the tapasvins praise, when they worship

The auspicious feet of the Arhat.

No wonder one who is used to worshipping in Hindu temples does not feel a stranger in jinalayas. Unlike Buddhism, the Jain religion seems to have given a very important place to temple worship. Jain temples, and the rituals held therein, are described in epics like Jivaka Chintamani and Chulamani. While the former has detailed descriptions of temples to the Arhat and even of a Kama Kottam (temple to Kama), the latter has a ‘Canto on Renunciation’ in which King Bayapati conducts worship in a Jina temple with scent, flowers, and water. He circumambulates the sanctum and recites a ten-verse prayer to the Arhat. While Vedic religion gave importance to yajna, and Buddhism frowned upon image worship, Jainism was for the consecration of holy images from the very beginning. Stone and metal were the favourite media; the paintbrush was also wielded with finesse. The first in the field, the Jains mastered sculpture and metal casting over two millennia ago, making the jinalayas treasure troves of devotional art.

Such temples were obviously innumerable in the first millennium. Today one goes in search of them with almost a hopeful hopelessness clutching one’s heart, remembering the poem by Sister Nivedita:

We hear them, O Mother!

Thy footfalls,

Soft, soft, through the ages

Touching earth here and there,

And the lotuses left on Thy footprints

Are cities historic,

Ancient scriptures and poems and temples,

Noble strivings, stern struggles for Right.

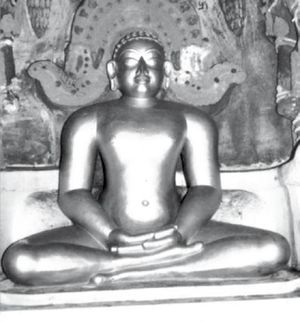

Two temples of Jain Tirthankaras built in the ninth century in Tiruparuttikunram, near Kanchipuram, are still intact. One is a temple to the eighth Tirthankara, Chandraprabha, and it is believed that Nandivarman Pallavamalla, king of Kanchipuram, built it. The adjacent Trailokyanatha temple has Mahavira as the main deity in the sanctum. Apparently the land was gifted to the Jain community by King Simhavishnu and his queen as early as the fifth century. Much later, Parakesarivarman Chola and Kulo thunga Chola granted whole villages to Jina Kanchi. Emperor Krishnadeva Raya, who did much to save Hinduism from Islamic depredations, also contributed handsomely to the temple to help restoration works in the seventeenth century.

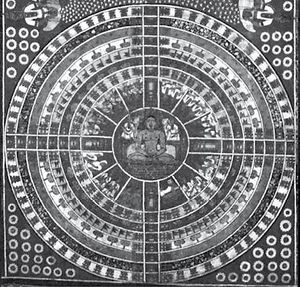

As the author gets to see these temples, he finds it hard to believe that they are under the control of the Archaeological Survey of India. He narrates thus, "An elderly lady, Padma, seems to be the caretaker; she willingly opened the main entrance after asking us sternly to deposit our cameras back in our car, while loudly complaining about how difficult it was to keep stray cattle and prowlers from entering the temple and desecrating them." The main door opens to a vast parikrama (circumambulatory corridor) and immediately before it is a dhvajastambha (flagstaff ) and balipitha (sacrificial altar). Going up a few steps is the Sangita Mandapam (musical hall) established by Irusappar, a Jain monk. The ceiling, held up by four rows of pillars, is full of paintings. Craning one's neck upwards, one can gaze at an astonishing sight. Though many of the paintings are faded, there are still plenty of them that create an illusion of movement: so many young women walking, young men carrying pitchers, elephants, horses. There is the painting of a Samavasarana lake in which the devout bathe before proceeding to listen to the wise. At the very centre of the huge circular lake, with four stepped pathways converging from the four directions, is the seated figure of the acharya. There are also serial paintings depicting incidents from Mahavira’s life. Some of the paintings seemed to be about the life of Dhivittan depicted in Chulamani. Dhivittan’s life has close resemblance to the saga of Krishna.

Wedged between the mandapam and the sanctum is the strong room where several ancient images of Arhats made of marble or bronze have been kept in safe custody. Some of the images are of gods and yakshis of Jain theology. The temple has huge open spaces, and a shrine nearby has the image of Arhat Pushpadanta installed in its sanctum. Going around the temple, one may well visualize King Bayapati’s reverence as he intoned the Chulamani prayer:

You have spread as light, this earth;

The earth is enveloped in your light.

Your reign brings grace to living beings;

Even the world of gods seeks your feet;

You have explained the eternal Truth;

Truth blossomed forth according to your will.

Recognizing the glory of your feet is Truth.

Once this is known, all else becomes clear.

In this context it would be well to remember Munaipadiyar’s Aranericharam, which has a verse that sought to clear the confusion in the minds of common people regarding various religions, at a time when temple structures were coming up very fast:

There is then the prayer from Tottira Tirattu (Anthology of Prayers) dedicated to the Arhat at the Trailokyanatha temple:

As the immortals ruling over the skies,

As the sub-humans in charge of the netherworlds,

As humans who enter the prison of the womb,

As animals and as ever so many forms

Have I taken birth for a long, long time

And suffered; I have now reached your temple

Auspicious, hoping to be rid of this cycle of birth.

O Mountain of molten gold

At holy Tiruparuttikunram near Kanchi!

Shiva Kanchi[edit]

Even though the area is called Shiva Kanchi, the Goddess Kamakshi takes precedence in Kanchipuram! The temple is spread out over an area of about five acres; the gleaming golden vimana of her temple attracts one’s attention immediately. Historians say that separate shrines for the goddess who was worshipped as the consort of Ekambareshwara were built only from the twelfth century onwards. The temple of Kamakshi, also known as Kamakottam, began as a Shakta centre (for worship of the Mother Goddess). Archaeological studies however claim a much earlier origin to the temple as one for a Jain Yakshi, when the holy place was known as Vimala Tirupalli.

The importance of Kamakshi for Shiva Kanchi may be traced to the Puranic narrative which says that she was originally worshipped as the consort of Ekambareshwara, being part of him in the Ardhanarishwara form.[5] According to the Kanchi Purana, Parvati once covered the eyes of Shiva in Kailasa, thus plunging creation into darkness, and consequently inviting a curse. She expiated her guilt by taking human birth and undertaking tapas, worshipping a linga made of sand. When the nearby river was in flood, she embraced the linga to guard it against the rising waters. Hence she is kama-kodi, the loving creeper that entwined herself round the Lord. In the course of evolution of her worship, the goddess began to be worshipped as the Durga of Kamakottam (the old temple), and later the present temple of Kamakshi was raised on what was apparently a Jain temple dedicated to a Yakshi.

The glorious city of Kanchi was put to the sword by the Islamic general Malik Kafur in the fourteenth century. Idols were broken down. The Kamakshi temple was one of the major victims. As in other Kanchi temples, worship was stopped in the Kamakshi temple too for several decades, till Kumara Kampana of Vijayanagar drove out the Muslim invaders and restored the religious ritual. From then on, the Vijayanagar kings took good care of Kanchi, of whom Emperor Krishnadeva Raya especially loved visiting this great city.

The Kamakshi temple today is at the very centre of the city, with the Ekambaranatha temple to the north-west and the Varadaraja temple to the south-east. It is interesting to note that all the major temples in the city are structured to face the prominent temple of Kamakshi with its four spires. The seated Kamakshi is a noble image, and to her front is the Sri Chakra in which the Mother Goddess is said to reside in her subtle form.

This city is rich in legends. We are told that originally Kamakshi was the fierce form of the supreme Goddess —ugrasvarupini. It was Adi Shankara who installed the Sri Chakra, which contained the ferocity of the goddess and transformed her into the calm and beautiful brahmasvarupini.

Kamakshi’s residence in her brahma-shakti form is in a cave below. She is said to have appeared on earth once to destroy demons, including the notorious Bhandasura. The Tapas Kamakshi (goddess undergoing tapas to expiate the sin of having closed the Lord’s eyes) has also been placed in the sanctum. Coming out of this garbhagriha, on the left is Kamakshi’s attendant Varahi. To her front is the santana stambha, indicating the place where King Dasharatha gained the boon of progeny from Goddess Kamakshi. In the first prakara (circumambulatory path) is the niche of Dharma Sastha (Ayyappan), with his consorts Purna and Pushkala. Tradition avers that Karikala Chola worshipped this Sastha, who gave him the deadly weapon called Chendu, which ensured his victory in the Himalayan regions. Though it is mistakenly believed in the niche that Sastha gave a bouquet of flowers (poo-chendu) to Karikala Chola, the fact that Sastha is represented with the typical Chendu weapon in his hands contradicts this belief.

There are innumerable temples dedicated to Shiva in Shiva Kanchi, and one can wander into any one of them and remain absorbed in the visuals as well as the devotional fervour evoked by aspirants going there for worship. Since Kamakshi reigns supreme in Kanchi, none of the Shiva temples have a separate shrine for the goddess, though an image is kept for ceremonial (utsava) processions. Many of the temples are thought to be several hundred years old. For instance, facing the western gate of the Kamakshi temple, is the Makalishwara temple, said to be the special residence of Rahu and Ketu. A snake called Makala attained mukti by worshipping Shiva in this area, and hence prayers are offered at the foot of the twin trees of neem and pipal, where a Naga (snake) has been consecrated.

Going out of the southern gate of the Kamakshi temple, is the celebrated Kacchapeshwara temple. As the presiding deity is mentioned in the seventh century classic Dandi Alankara, the temple is very old. Legend speaks of Mahavishnu in his tortoise form, worshipping Shiva at this place. Apart from the sanctity of the temple, what strikes one the most is a series of Buddhist figures on the stone pillars of an inner mandapa, strongly suggesting that these pillars have been taken from a Buddhist vihara. Perhaps the vihara was the original structure and when it came down to make way for a Shiva temple several centuries ago, some of the masonry was reused by the builders.

There are also other Shiva temples like Suragaresha, Siddhishwara, Manikandeshwara, and Ramanatheshwara. The one to Lakulishwara (Dhavaleshwara) is associated with yogis and siddhas. From the seventh century onwards, when the Nayanmars went round singing their mellifluous songs on Shiva, there was a tremendous spurt in temple-building activity. Though the corpus of devotional hymnology pertaining to Shiva Kanchi is vast, only five temples have been hailed by the Nayanmars in their hymns. They are Ekambareshwara, Tirumetrali, Onakan-thanthali, Anekathankavatam, and Kachinerikkarai-kadu. Thus Tirunavukkarasar worshipped Ekambareshwara and the goddess Elavarkuzhali with an exquisite decad:

He is the God of Dissolution; He is the King who smote Death;

He is earth; He became water of the earth; He is wind;

He is fire; He is rumbling thunder and lightning;

His is the glorious, coral-like ruddy body bedaubed

With white ash; on His crest floats the crescent; on His long

Matted hair He sports the Ganga of abundant water;

He is Yekampan of Kacchi girt with beauteous groves;

Behold Him, the one enshrined in my thought! [6]

Of the two major Shiva temples, Ekamabaranatha’s raja-gopuram, built by Krishnadeva Raya in the sixteenth century, rises to 192 feet. Originally planned and structured by the Pallava kings of Kanchi on a spread of twenty acres, this temple was further embellished by the Cholas and the kings of Vijayanagar. The deity here represents the element, earth (prithvi). The consecrated tree is mango, and according to local legend, it is 3,500 years old. The famous shrine of Vikatachakra Vinayaka is in the Thousand Pillar Hall, and the pillars stand witness to the mastery of sculpture by the workmen of earlier centuries. Another important landmark is the temple to Subramanian known as Kumarakottam, which has been made famous by Kachiappa Shivachariar—whose epic Kanda Puranam was first recited in the mandapam of this temple.

The celebrated Kailasanatha temple was built by Rajasimha (Narasimhavarman Pallava II) and his son Mahendra III. If it is exciting to go into the smaller Shiva temples in Kanchi and wander around watching the sculptures and searching for Jain or Buddhist remains of an earlier era, or to keep gazing at the Buddhist figures in meditation on the higher reaches of an outer wall of a temple, it is an experience of a lifetime to enter the Kailasanatha temple at the periphery of the city. The sanctum has a huge linga, symbolizing the Supreme, while on the rear wall, one can watch wide-eyed the sumptuous Somaskanda panel. Shiva and Parvati have Subramania between them (on the lap of his mother), with Brahma and Vishnu watching the group in adoration. The outer wall of the sanctum is an amazing panorama of gods and goddesses. In between the two walls is a very narrow passage for parikrama. One has to crawl to enter it and also to come out of it. To quote the officiating priest, ‘This is the entry into heaven, the Swarga Vasal, and if you do the pradakshina, it is like having another birth, along with Shiva’s grace.’

The temple, built in sandstone with nearly sixty planned niches, seems to be the work of master craftsmen. The intricate carvings of divine beings, a never-ending repeat of the Somaskanada panel, the mythic lions and the imposing Nandis are very unique in their depiction. There is a depiction of Vishnu holding up the Mandara mountain as gods and demons churn the ocean, and a little further away, there is the confrontation between Shiva and Arjuna. Soon comes Shiva destroying Yama, and again dancing with a damaru in his hand in gay abandon.

‘The cells of many of these contain traces of old paintings on plain walls or painted stucco over reliefs. The external reliefs of these parivara [family] shrines of the malika [cloister gallery] contain a variety of sculptures, both Saivite and Vaisnavite, of varied iconography, thus making this temple complex a veritable museum of iconography and plastic art. The sculptures include the dipkalas[the guardian deities of the directions] and Ganesh, who makes his first appearance in Pallava temples, as also the Saptamatrika group, Chandesa and other parivara deities.’[7]

There is a charming legend connecting the construction of this temple with Pusalar, a Nayanar whose history is recounted by Sekkilar. When the Pallava king Rajasimha had completed the splendid temple to Kailasanatha, an auspicious date for the consecration of the temple was chosen by his chief priest. However, the deity appeared in Rajasimha’s dream and said that the date of consecration would have to be changed as the Lord was to be present in the magnificent temple being consecrated by Pusalar in Tiruninravur (Tinnanur) at the same time. The king was mystified; how could a huge temple be built in his own kingdom without his knowledge? So he hastened to Tiruninravur. No temple was to be seen there. On making enquiries, he learnt that one poor brahmin, Pusalar, had been going around saying he was building a temple to Shiva and would daily announce the progress in the works. The king went to Pusalar and spoke to him of his dream. The poor devotee exclaimed: ‘Alas! I have built only in my imagination. Did the Lord really take notice of my desire?’ The king saluted the devotee with reverence and returned to his capital. Pusalar’s sincerity became legendary, and he is honoured as the Nayanar of whom Sekkilar sings in his Periya Purana':'

Let us recollect Tiruninravur’s Pusalar

Who wished to build a temple to Shiva

But had not the wherewithal.

And how he built a temple in his mind. …

Having decided, he tried for money.

‘How shall I build without capital?’

He began collecting everything needed

To build, all in his imagination.

He got materials and carpenters,

Decided upon a date to lay the foundation,

Planned everything according to the Agamas

And built without sleeping even at night. …

He (the King) came to the place and asked

Those present: ‘Where is Pusalar’s temple?’

‘Pusalar has built none’, they replied.

‘Let all scholars come’, the king said. …

After consecrating Shiva in the mind-temple

At the auspicious time, and having performed

Worship for a long time after,

The devotee reached the feet of Shiva.[8]

The legend indicates the richness of the temple-building activity of the times as well as the widespread dissemination of Sanskrit Puranas that led to the inextricable association of temples with Indian tradition.

For Shiva Kanchi, the Kanchi Kamakoti Math is a major Shaivite presence. Tradition avers that Adi Shankara went to the Himalayas and had the darshan of Shiva and Parvati. He brought the sphatika (crystal) linga given to him by Shiva to Kanchi where he established a monastery and installed the linga for regular worship. Among the pontiffs who graced the math in recent times, Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswati, popularly known as the Paramacharya, took the math to great heights by initiating a resurgence of Indian culture. Vedic studies, renovation of temples, and traditional arts like sculpture and architecture have been given a great fillip. The math also provides medical help to the masses .

The Jnanaprakasar Math has done priceless service to Shiva Kanchi by propagating the Shaiva Siddhanta, probably the oldest tradition of its kind. Apart from ritualistic worship of the Meykandeshwara Linga, the math organizes lectures on philosophical and theological aspects of Shaivism, as propounded in the fourteen Meykanda Shastras.

Shiva Kanchi is so rich in tradition that it can be experienced over and over again. Devotees from all over the world eagerly flock here to experience the calm of mind made passionless by the blue-throated Lord:

Like the faultless lute, the moon at night

The southern breeze, the brilliant spring,

The scented lake covered by humming bees,

Is the cool shade of my Lord Shiva’s feet.[9]

Vishnu Kanchi[edit]

In the celebrated poem Vishwagunadarsha Champu by Venkatadhvari, the gandharvas Krishanu and Vishwavasu are found flying over India in an airborne vehicle commenting on various well-known pilgrim centres. Krishanu is always critical, but Vishwavasu can only see the good in everything. A very instructive and informative poem, the champu moves southwards from Badrinath to Chennai and thence to Kanchipuram. Vishwavasu gives a very warm description of the city, and salutes Varadaraja: ‘As we reach the Hasti Hill, we salute the Eternal Flame (Dhama Sthiram) which rivals Kamadhenu (the cow of plenty) and the “wish-yielding tree”, guards Indra and other deities, is holy, and has eyes that are cool with compassion and lips that are scented with yajna ingredients.’ But as he recounts the legends concerning Varadaraja, Krishanu feels that he needs to put a spoke in his wheel of enthusiasm: ‘After all he (Varadaraja) stopped the progress of Saraswati. How can you praise him!’

The foremost temple of Vishnu Kanchi (also known as Chinna Kanchipuram) is that of Varadaraja, located in the eastern quarter of the city. The Puranic legend about the origins of the temple is easily told. Once upon a time Lakshmi and Saraswati went to Indra to find out who between them was superior. Indra spoke in favour of Lakshmi. Saraswati cursed him to be born as an elephant. She went to Brahma but he too said that Lakshmi was superior. Incensed, Saraswati took away his Creator’s Staff . Brahma performed tapasya to regain his staff . Narayana appeared to him and told him that if he (Brahma) could perform a sacrifice in Satyavrata Kshetra (Kanchipuram), he would get back his staff, as a yajna performed in this holy place is equivalent to one thousand Ashwamedha yajnas. Saraswati rushed upon Brahma’s yajna as a flood, but was stopped midway by Vishnu, who lay across the path. Brahma successfully completed the sacrifice and out of the sacrificial fire rose Narayana as Varadaraja (one who grants boons). The Lord returned to Brahma his srishti danda. At that very moment, Indra, who had by now become the Hasti (Elephant) Hill, got Vishwakarma to construct a temple atop the hill for Varadaraja.

Historically speaking, the temple is more than a millennium old. Those who contributed to its building and growth include the Cholas, beginning with Rajaraja the Great (1018–54 CE), Pandyan kings like Sundara Pandya (13th cent.), the Cheras, and the Hoysalas. From the fourteenth century onwards the kings of the Vijayanagar Empire took great interest in the temple. Their spiritual mentors included Kotikannikadhanam Lakshmikumara Tatadesikan, of the famed line of Tatacharyas who were custodians of this temple. Among the mammoth structures built during this period is the celebrated Kalyana andapa, verily a connoisseur’s delight. Each of the ninety-six pillars is exquisitely sculpted with innumerable figures. Some figures actually seem to be ready to leap towards us. Vishwamitra performing tapasya as Mena ka dances, a cat trying to catch a dove, Hanuman giving the signet ring to Sita, the battle of Krishna and Jambavan, Rati and Manmatha flying on their parrot and swan mounts, and gopika-vastrapaharana (stealing of the gopis’ clothes) are some of them. There are scenes from the Ramayana and also trick sculptures aplenty— like a figure with three faces, four hands, and four legs; four monkey faces on the bodies of two monkeys; and an elephant when seen from the front appearing as a bull from behind. The irresistible marvels of this mandapam include the hanging stone chains. All the links in a given chain, including the stone plate from which it hangs, have been cut out of a single block of stone!

This Kalyana Mandapam is immediately to the left from the Varadaraja Temple’s front gopuram, which rises to thirty metres with seven tiers topped by nine kalashas (rounded pinnacles). Immediately behind the mandapam is the sacred pond, Ananta Pushkarini. Aththi Varada (an icon of Varadaraja made of wood, said to be the original deity worshipped in the sanctum) rests in a silver box beneath the waters and is displayed once in forty years. On three sides of this pond are various shrines. Lakshmi Varaha in a tiny niche is verily a poem sculpted in stone. Other deities enshrined in this area include Ranganatha and Sudarshana.

Going towards the hill which forms the centre of the complex, is the place to offer first salutations—to Yoga Narasimha in a cave. The Hasti Hill rises above this cave and has the sanctum of Varadaraja at the top. Varadaraja is seen standing, facing west. The utsava vigraha (the image used for festive outings) of Varadaraja has marks on the face. The priest explains that these are due to the heat of the sacrificial fire from which the Lord appeared on earth. For just a few minutes, one takes in the scene, and then the veils of history enclose to recreate yet another mystic drama that was enacted in this tiny space!

Sri Ramanuja’s formative years were spent here as a student. One of his teachers was Tirukachchi Nambi. Nambi’s duty was to wave the chowry for the deity in the sanctum. Belonging to the trader caste, Nambi was a very humble man. So pure was his devotion that the Lord would have a dialogue with him whenever they were alone. We are assured by legends that one day Nambi was able to get answers directly from the Lord for the questions that had been troubling Sri Ramanuja. Other spiritual luminaries associated with Varadaraja are Nadathur Ammal, Kuresha, and Vedanta Deshika.

Kuresha (Srivatsanka Mishra) was the earnest disciple of Sri Ramanuja who saved his master from an inimical Chola king. But he was himself imprisoned and had his eyes gouged out. When he was released, he went to his master, Sri Ramanuja, who asked him to go and pray at Kanchipuram, since Varadaraja was an unfailing giver of boons. It is true that Kuresha lacked the physical vision to see the deity, but Varadaraja was a familiar presence to him, as he had grown up in Kuram, close to Kanchipuram. So Kuresha went to Kanchipuram, stood before the Lord in the sanctum, and offered his supplication through one hundred and two verses that became famous as the Sri Varadaraja Stava. We are told that when he was actually reciting the poem, the deity grew compassionate and asked him to choose a boon. Though Sri Ramanuja had hoped that Kuresha would ask for the restoration of his eyesight, the humble sadhaka wanted only paramapada (supreme beatitude) for the one who had harmed him: ‘The ananda that I am going to gain must be the portion of Naluran also!’ (It had been under the instigation of Naluran that the king had turned inimical towards Sri Ramanuja and passed the order to gouge out Kuresha’s eyes.) Touched by the devotee’s kindness even to an enemy, Varadaraja gifted him the ability to perceive his divine form as also that of Sri Ramanuja. The radiant poem by the aged devotee is couched in easily sung Sanskrit.

A magnificent description of Varadaraja marks the opening:

"May the Lord who has been described as unequalled and peerless by the accents of the Upanishads, Hari, who is atop the Elephant Hill, always grant me the good. I surrender unto him who is a treasure to Lakshmi-Perundevi Thayar, a shoreless treasure unto those who seek his help, one who has vowed to grant the purusharthas desired by devotees, who is ever concerned with the well-being of all living beings, whose treasure is compassion, the king of all, the lord of immortals".

Having assured himself and all those who would read the stotra (hymn) as a manual of sadhana that Varadaraja is the never-failing goal, Kuresha seeks to image the Supreme Being verily as a Self-created Brilliance on the Hastigiri, and surrenders to the hill itself for having made this image hailed in the Vedas perceptible to human sight.

Vedanta Deshika was the author of several stotras, the epic Yadavabhyudaya, and the drama Sankalpa-suryodaya in Sanskrit. At the same time, he had an unrivalled mastery of Tamil and was immersed in the hymns of the Alvars. Once, the traditionalists of the Varadaraja temple objected to his reciting Tamil hymns in the prakara (circumambulatory path around the shrine). Vedanta Deshika argued with them and won. He then wrote the poem Tiruchchinnamalai in praise of Varadaraja, which is recited whenever the Lord is taken out in procession.

Just outside Varadaraja’s sanctum and towards the right in the prakara, are the twin lizards in the eastern corner. This is a very popular sight and is considered sacred. Etched on the roof are two lizards with two circles that seem to represent the sun and the moon. Legend says that these lizards were originally brahmana boys. Once they went to the forest to bring water for their guru, Rishi Gautama. They inadvertently left the pot uncovered, and when Gautama wanted to use the water, out leapt a lizard. The reship cursed his disciples to be born as lizards for a while for their carelessness. After they were released from the curse, Indra had a gold and a silver lizard made, and announced that whoever stands in this corner marked by the lizards and looks at the Hastigiri will get the merit of having recited Hari’s name on an ekadashi, the auspicious eleventh day of the lunar fortnight.

Coming down the steps, is the location to offer salutations at several shrines to such divinities as Dhanvantri, Malayala Nachiyar, and Perundevi Thayar (Goddess Mahadevi). Perundevi Thayar is a very noble presence who never fails to grant a sincere prayer. It is said that once Vedanta Deshika wanted to help a young brahmacharin who needed money to get married. When he composed and recited the Sri Stuti in the presence of Perundevi Thayar, there was a shower of gold. We now climb down to level ground and then go around another huge prakara which has niches to acharyas like Nammalvar, Ramanuja, Varavara Muni, and Vedanta Deshika.

Apart from Varadaraja’s temple, Kanchipuram’s Vaishnava ambience includes several other renowned elements of history, architecture, and literature. There is the temple at Urakam where the mulavar (main deity) is Trivikrama in a massive sculpted image. He has both his hands stretched sideways and the left leg lifted upwards in the act of measuring the skies. In the same temple, a visitor can salute three deities that were not originally residents of this temple: Jagadishwar of Tirunirakam, Karunakara of Karakam, and Karvana Perumal of Tirukarvanam. In times of political disturbance, these images were brought here for safe custody and have remained here ever since. A little distance away from the front of this temple is a popular shrine to Chaturbhuja Anjaneya. Among other sacred places that are associated with Vaishnava presence in Kanchipuram are Tiruvehka (with Yathokathakari as the deity), Ashtabhuyakaram (Gajendravarada), Tiruthangal (Dipa Prakasha), Tirukalvanur (Adivaraha), Tiruvelukkai (Narasimha), Tirupadakam (Pandavaduta) and Tirupavalavannam (Pavalavannar).

While all these temples have somehow survived the onslaughts of time thanks to the unswerving faith of the devotees, it is Parameshwara Vinnakaram which is talked about much for its history and art. Situated within a kilometre of the Kanchipuram railway station, this is one of the most ancient Vishnu temples. It is built in sandstone with an admixture of granite. The place was originally a math and was used by pilgrims on their way to Banaras. The present structure was built by the Pallava king Parameshwaravarman (also known as Nandi-varman II) in the eighth century. It has three sanctums, one above the other. Vishnu is in the asana or sitting posture (Vaikuntha Perumal) in the sanctum on the ground floor, in the shayana or reclining posture (Ranganatha) on the first floor and in the sthanaka or standing posture (Paramapadanatha) on the second floor.

There are innumerable legends concerning this temple, which has been sanctified by the hymns of Tirumangai Alvar. According to one of them, Parameshwaravarman was gifted as a baby to his parents by the Lord himself, who came to them in the guise of a hunter. Since he grew up drinking the milk of elephants, he is said to have presented eighteen elephants to this temple.

What is unique and breathtaking in this temple is the unending series of sculptures in the prakaras. Having been carved out of sandstone, they started crumbling, but restoration work by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has helped considerably. One is left dumb with astonishment at how the chisel of the sculptor that has created a video effect through several series: the battles between Pallavas and Chalukyas; the destruction of Hiranyakashipu by Narasimha; the killing of Narakasura by Krishna; the slaying of Vali by Rama; the events concerning the birth of Parameshwaravarman, his coronation, and the Lord teaching the king all the shastras are some of them. The Pallavas were fond of performing the Ashwamedha sacrifice and this too has been illustrated. One can even see a pilgrim from China carved on the wall.

In more recent history, Krishnadeva Raya of Vijayanagar provided amply for the upkeep of the temple. At present, it is under the control of the ASI. Just beside the temple there is a mosque. The mosque shares the tank of the ancient temple, underlining the tolerant attitude that prevailed here.

Kanchipuram is inexhaustible. One is simply overwhelmed by the legends, history, and historical monuments in the city and its environs. The city appears to be a crucible in a divine laboratory. Religion and spirituality are seamlessly woven into secular life even today. The presence of several maths needs to be mentioned in this context. These include the Tondaimandala Adhinam, which is Shaivite and is headed by Sri Jnanaprakasha Deshika Paramacharya; the branch math of Tiruvavaduthurai Adhinam headed by Sri Sundaramurti Tambiran; the Upanishad Brahmendra Math, which has a famous icon of Dakshinamurti; and of course the Shankara Math guided by its pontiff , Acharya Sri Jayendra Saraswati. We also have now the Sri Ramakrishna Math at Karaipettai that is working ceaselessly for the strengthening of the bases of education, culture, religion, and spirituality that have made Kanchipuram famous for several millennia and drawn from Kalidasa the priceless compliment: ‘As is jasmine amongst flowers, Vishnu amongst men, Rambha amongst women, so is Kanchi amongst cities!’

Note

1. Varadaraja is said to have risen from the sacrificial fire at the yajna performed by Brahma on the banks of the Vegavati river.

References[edit]

- ↑ "Perumbanatruppadai," Translated by N Raghunathan.

- ↑ ‘…within Beloved-of-the-Gods King Piyadasi’s domain, and among the people beyond the borders the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Satiyaputras, the Keralaputras, as far as Tamraparni and where the Greekking Antiochos rules, and among the kings who are neighbors of Antiochos, everywhere has Beloved of-the-Gods King Piyadasi made provision for two types of medical treatment: medical treatment for humans and medical treatment for animals. (English rendering by Ven. S Dhammika.)

- ↑ The Tamil term ‘Katavut Palli’ has been explained as a temple to Buddha by scholars.

- ↑ Madurai-k-kanji, Translated from Tamil by Prema Nandakumar

- ↑ For further information on the subject, see R Venkataraman, Devi Kamakshi in Kanchi (Srirangam: Vani Vilas, 1973).

- ↑ Translated by T N Ramachandran.

- ↑ K R Srinivasan, Temples of South India (New Delhi: National Book Trust, 1991), 116.

- ↑ Periya Purana, 65.1,5, 6, 12, 17.

- ↑ Tirunavukkarasar Tevaram, 90.1.

- Originally published as "Kanchipuram, the Four-fold Glory" by Prabhuddha Bharata May 2007

, June 2007

, July2007

and August 2007

editions. Reprinted with permission.