By Swami Varishthananda

Varanasi is famous for two things—learning and burning.

If Hinduism has a spiritual capital, it's Varanasi. Is has had many names, and even in modern times it is addressed as Kashi and Vishwanath. Of the Buddhist scriptures, the Udaya Jataka calls it 'Surundhan', the Sutsoma Jataka 'Sudarshana', the Sondand Jataka 'Brahmavardhana', the Khandahal Jataka 'Pushpavati', the Yuvanjaya Jataka 'Ramma Nagar', the Sankha Jataka 'Molini'. In the 2nd century BCE businesspeople referres to it as 'Jitvari' because of the "wins" (in profits) they had there.[1] It is also referred to as Ketumati, a paradise of Buddhas.

Varanasi is the city of ethereal holiness and sanctity. Situated on the western bank of the Ganga as it takes a northward turn in eastern Uttar Pradesh, it is bounded by the small tributaries Varuna and Asi, which give it its name. It is also known as Kashi, the city of light and liberation. This name is derived from the same Sanskrit root prakāśa, which means light—kāśayati prakāśayati iti kāśi. This is the story of the eternal abode of Baba Vishwanatha, the Lord of the Universe, the presiding deity of the city, the raison d’être of this ‘holiest of holy’ cities—a place of pilgrimage. Another name of this city is Benares, the corrupted English form of the original Pali ‘Baranasi’—the city of sannyasins and sages, of savants and scholars, of statesmen and stars, of saints and sinners.

Banaras, the city of Baba Vishwanatha, is unique in more than one way. It has rarely been an important political center, and the rise and fall of its rulers throughout its long history has had little impact on the story of the city’s sanctity. Kashi, to a large extent, has maintained an age-old and hoary living tradition right up to the present day, and is therefore the cumulative face of the Sanatana tradition.

The Holy City of Vishwanatha[edit]

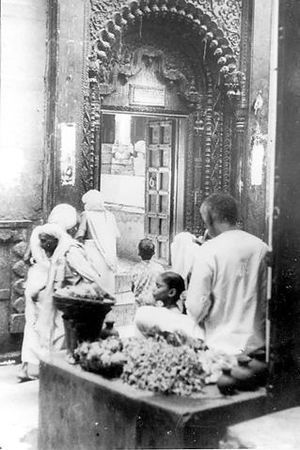

The quintessence of Varanasi is its vibrant spiritual atmosphere. This eternal city of Lord Shiva does not get destroyed during pralaya and is considered to be resting on the trishul of Shiva. Topographically, the three main Shivas—Omkareshwara, Vishweshwara (Vishwanatha), and Kedareshwara are indeed situated on top of three hills which constitute Varanasi. Even today when one enters the shrine of Baba Vishwanatha, as the Lord of the Universe is lovingly called by his votaries, after having taken a dip in the purifying waters of the Ganga and having wound one’s way through the reassuringly familiar Vishwanatha Gali (lane), and having paid one’s obeisance to Dhundhiraja Ganesha, in the midst of much hustle and bustle with sounds of ringing bells and chants of ‘Hara, Hara, Mahadeva’ reverberating all around, this dense spiritual atmosphere is palpable; it envelops perceptive devotees and raises their consciousness to the feet of the Lord, where it remains effortlessly held.

The atmosphere of holy spirituality is densest within the precincts of the shrine of Vishwanatha, especially in the sanctum sanctorum; yet the whole atmosphere of Varanasi is spiritually surcharged and is especially conducive to religious and scholastic pursuits and spiritual growth.

Across the lane that leads to the golden-spired shrine of Baba Vishwanatha, is the temple of Ma Annapurna. These two temples symbolize the essence of culture, eloquently articulated in this well-known couplet:

| Mātā me pārvatī devī pitā devo maheśvara; |

My mother is Devi Parvati; my father Lord Maheshwara, my relatives are Shiva’s devotees, and |

Even today, two Banarasis meeting within the precincts of these temples will joyously greet each other with ‘Hara, Hara, Mahadeva, Hara, Hara, Hara!’

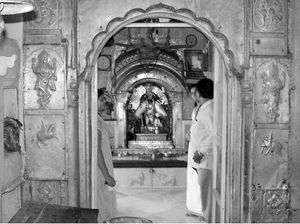

Both these temples have a number of smaller shrines within their precincts. Mother Annapurna’s is a ‘golden’ image with a bowl and spoon in hand—she feeds the entire universe with anna (food). Besides the image in which she is available for daily darshan, there is one made of solid gold which is unveiled for darshan only on the three days of Diwali. Devotees consider the darshan of the golden Annapurna to be especially efficacious for obtaining life-sustaining anna! On the last day of this darshan, the Annakuta (mountain of food) festival is observed in the temples of both Mother Annapurna and Baba Vishwanatha. The one prayer which all her devotees have in their hearts and on their lips is:

| Annapūrṇe sadāpūrṇe śaṅkara-prāṇa-vallabhe; |

O Annapurna, who art ever-full! O beloved of Shankara! O Parvati! Grant us alms that |

Though the shrines of Baba Vishwanatha and Ma Annapurna are the principal temples of Kashi. Tirtharaja Kashi has numerous other shrines, including those corresponding to other important shrines—from that of Kedaranatha in the north to Rameshwaram in south India. In fact, there is a popular Hindi saying: ‘Kashi ke kankar sab shiv shankar; even the pebbles of Kashi are all Shiva!’ However, among the numerous shrines in this city of temples—each with its own uniqueness and glory—the important ones include the temples of Sankata Mochana, Durga Kunda, Kedaranatha, Kala-Bhairava, Vireshwara Shiva, Bindu Madhava, Tila-bhandeshwara, Bharata Mata, and Vishwanatha (at Banaras Hindu University).

The medieval poet-saint Tulsidas was one of Kashi’s famous residents. It was his daily practice to pour some water at the foot of a certain tree. A ghost who happened to live on this tree—and ghosts are known to be particularly thirsty creatures— was highly pleased with this service of Tulsidas’s and decided to grant him a boon. The devotee that he was, Tulsidas asked the ghost for a vision of Sri Rama. The ghost directed Tulsidas to a place where a discourse on the Ramayana was in progress and which Hanuman was attending in the guise of an old Brahmana afflicted with leprosy. Tulsidas went to the designated spot, recognized Hanuman, and was directed to go to Ayodhya for the darshan of Sri Rama. Tulsidas, in turn, requested Hanuman to remain in Kashi for the good of the world. Later on, digging deep at that very spot, Tulsidas discovered an image of Hanuman. This he consecrated as Sankata Mochana—the remover of perils. Hanuman or Mahavira is Rudravatara—the incarnation of Rudra-Shiva. He is a great devotee of Sri Rama. The temple of Sankata Mochana is an important place of religious worship and cultural festivities.

Next to Sankata Mochana is the famous temple of Divine Mother Durga—popularly known as Durga Kunda because it is situated beside a big tank with the same name. The Devi Mahatmya reminds us that people worship Mother Durga because—

| Durge smṛtā harasi bhītim-aśeṣa-jantoḥ svasthaiḥ smṛtā matim-atīva śubhāṁ dadāsi; |

Remembered in distress you remove the fears of all beings, remembered in happier times you bestow the most beneficent of intellects; who other than you—whose heart bleeds for all—can remove poverty, unhappiness, and fear? |

Varanasi has the unique distinction of having separate temples dedicated to all the nine forms of Mother Durga:

- Shailaputri,

- Brahmacharini,

- Chandraghanta,

- Kushmanda,

- Skandamata,

- Katyayani,

- Kalaratri,

- Mahagauri, and

- Siddhidatri,

as well as to all the nine manifestations of Gauri.

Not only the Gods, but all the tīrthas too reside in Varanasi. One of the most famous of these tīrthas is Kedareshwara. Situated on the banks of the Ganga, a steep flight of steps leads up to this temple with red and white vertical stripes painted on its outer walls in the fashion of South Indian temples. This linga of Shiva is svayaṁbhū, ‘self-manifest’. However, the location of this tīrtha in Kashi endows the entire Kedara kṣetra (territory) with power to directly liberate all persons who die within its territory, without even having to suffer at the hands of Kala Bhairava, the master of time.

Another important kṣetra is the Siddha Kshetra, the ‘Field of Fulfilment’. Here, above the Scindia Ghat, is the temple of Vireshwara, or ‘Lord of Heroes’. It is said that the sage Vishwanara, yearning for a son, did tapasya here and was blessed with a son, Vaishwanara, through Shiva’s boon. Even to this day Vireshwara Shiva is propitiated by couples who wish to have a son.

Immediately south of Scindia Ghat is Manikarnika Ghat, famous throughout India as the cremation ground where Shiva and Parvati confer liberation upon departed souls. It is this Manikarnika Ghat, along with the Harishchandra Ghat, named after the famous king whose name is synonymous with truth and generosity, that makes Kashi famous as the place of liberation through death. This mukti is sought after by numerous devotees, especially in their old age.

To the north of Scindia Ghat is the famous temple of Bindu Madhava. The story of Kashi temples and of pilgrimage to Kashi remains incomplete without a visit to the Kala Bhairava temple, the guardian angel of Kashi. Kala Bhairava has dogs for his mount which makes the residents of Kashi, wary of harming even stray dogs within the precincts of the city.

Finally, there is the modern Kashi Vishwanatha temple on the Banaras Hindu University campus. The uniqueness of this modern two-storied temple is that it has shrines dedicated to each of the five important deities—Shiva, Vishnu, Durga, Ganesha, and Surya—with the sun shining outside the temple! But that is not all; adorning the walls of this temple are murals depicting the best of tradition—from health, through history. It is a rare treat to spend a few hours in this temple with a knowledgeable guide, to be educated about the best elements in culture—grammar, chemistry, statecraft, language, and architecture; the spiritual tradition of the Vedas, Upanishads, Ramayana, Mahabharata, Bhagavata, and Durga-saptashati; the inspiring lives of saints and sages; family life and world peace; as well as Sankhya and Yoga. It also has the entire Bhagavad Gita inscribed on its walls.

Like the temple it houses, Banares Hindu University or BHU is also unique. Apart from being reckoned the largest residential university campus in Asia—its two campuses are spread over 1,300 and 2,700 acres respectively—it is a seat of learning for virtually every important occidental and oriental branch of knowledge. The 3 institutes with 15 faculties and 127 departments of the university provide residential educational facilities in a host of disciplines—from Sanskrit studies and theology to rocket, missile, and ceramic engineering—to tens of thousands of students on a single campus. The education is subsidized and places little economic burden on the students. The university also has a museum, Bharat Kala Bhawan, with nearly a lakh exhibits including a rich collection of Indian miniature paintings, sculptures, a rare philatelic and numismatic collection, unique textiles, and galleries dedicated to Alice Bonner, Nicholas Roerich, M K Gupta, and Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya, the founder of BHU.

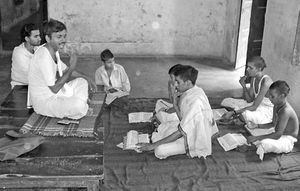

There are two other universities in Varanasi— the Mahatma Gandhi Kashi Vidyapith and Sampurnanand Sanskrit University. Besides, the city is also home to two deemed universities—the Safia Islamia and the Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies, as also two autonomous colleges: Udai Pratap College and Agrasen Girls Postgraduate College. Apart from these institutes of higher learning, Varanasi has numerous schools and colleges as well as many trusts and private institutes committed to good education. But it is the pundits of Varanasi that are especially famous throughout the length and breadth of the country, not only for their depth of scholarship, but also for not accepting money to impart knowledge. This is true of both monastic scholars as well as householder pundits. It is remarkable that in these days of globalization and commercialization Kashi still has great householder-scholars painstakingly imparting knowledge even to pupils of great means without accepting any monetary remuneration.

It was at Sarnath near Kashi that Bhagavan Buddha set in motion the ‘wheel of Dharma’ with his first sermon following enlightenment. Sarnath had a huge Buddhist monastery as well as three stupas and an Ashokan pillar with a lion capital on top. The Sarnath museum is renowned for its pre-Gupta and Gupta period sculptures, of which the meditative Buddha and the Ashokan Lion Capital are the most famous. Saranath is also home to the Mahabodhi Society, which was started by Angarika Dharmapala on his return from the World Parliament of Religions—where he had been one of Swami Vivekananda’s co-delegates. With its many Buddhist and Jain temples, Sarnath is an important tourist and pilgrimage place for Buddhists and Jains alike. Varanasi and the neighboring district of Jaunpur are also famous seats of Islamic studies.

The City of Shiva[edit]

Varanasi is the city of Bhagavan Shiva: Shiva, the Mahayogi, the lord of yogis; Shiva, the Nataraja, the lord of dance and music; Shiva, the jyotirlinga, the Light Supreme, Knowledge Supreme! Varanasi is truly the city of enlightenment, of illumination, of light.

In the Purana-s, it is mentioned that when Bhagavan Shiva, the mountain ascetic, descended from the realm of perpetual meditation and married Parvati, daughter of the Himalayas, he chose the city of Varanasi, a beautiful place spanning a radius of fivekrośas (ten miles), as their home; a move that played a major role in the ascendancy of Shaivism in north India. Over the centuries, Kashi’s connection with Shiva became so firm that by the time of the Kashi Khanda, this city came to be seen as the ‘original ground’ created by Shiva and Parvati, upon which they stood at the beginning of time; a place from which the whole of creation came forth in the beginning, and to which it will all return in the fiery pralaya at the end of time. The legendary king Divodasa had once managed to occupy Kashi and evict Shiva and other deities on the strength of his virtue, dharma. After numerous efforts by the Gods to induce Divodasa to err from dharma had failed, Shiva sent one of his attendants (gaṇas), Nikumbha, to empty the city for him. Nikumbha appeared in a dream to a barber, telling him to establish and worship the image of Nikumbha gaṇa (Ganesha) at the edge of the city. The barber did this, and Nikumbha Ganesha, the ‘lord of gaṇas’, became popular with the citizens of Kashi for granting boons to those who propitiated him. Now, King Divodasa’s wife, Suyasha, was childless. She worshiped Nikumbha on several occasions to get a son, but her prayers were not answered. Enraged, Divodasa ordered the shrine of Nikumbha Ganesha destroyed. This provided Nikumbha the opportunity to pronounce a curse on the king and have the city emptied of all its inhabitants. When the city was vacated, Shiva arrived and re-established his residence there. Apparently Parvati was not fond of the city at first, but Shiva said to her, ‘I will not leave my home, for this home of mine is “Never-forsaken; Avimukta”.’ Such is Shiva’s attachment to Kashi, the Avimuktapuri.

City of Saints[edit]

The legend of King Harishchandra is often narrated as the benchmark of an ideal life. He was known to always keep his word and never utter a lie. These twin qualities were tested heavily through various circumstances that led him to penury and separation from his family; but he never flinched from his principles. The sage Vishwamitra once approached him at Ayodhya and, reminding him of an earlier promise he had made, asked Harishchandra to give him his entire kingdom. Harishchandra immediately made good his word and started walking away with his wife and son, sans property, to Banaras. But the sage then demanded an additional amount as dakṣiṇā (honorarium). To pay this, Harishchandra, with no money at hand, had to sell his wife Chandramati and son Rohita to a brahmana family, and himself to a guard in charge of collecting taxes for the bodies to be cremated at the local cremation ground. Sometime later, Rohita was bitten by a snake and died. Chandramati took him to the cremation ground. Seeing her with the dead child, Harishchandra was stung by pangs of agony. But, duty-bound as he was, he asked for the taxes required for cremation. Chandramati offered him the only dress she had, the sari she was wearing, as tax. When she proceeded to remove her dress, the devas along with Vishwamitra appeared on the scene and, pleased with the unassailable character of the king, brought his son back to life, and offered a heavenly abode to the king, the queen, and all their subjects. This moving story is known to have particularly affected Mahatma Gandhi, who, after having watched a play on Harishchandra as a child, became deeply influenced by the virtue of truthfulness.

In keeping with this tradition, many great saints and sages made Banaras either their home or their workplace. Maharshi Veda Vyasa, credited with writing the Puranas and the Mahabharata, is reputed to have spent his life working in Kashi. He composed his Brahma Sutra in this very city. Sri Shankaracharya too came to Kashi and made it his workplace for quite some time—arguing that this especially sacred land would give him the zeal and energy to work in a more devoted manner. Many of his works were composed here in Kashi.

The Bhakti Movement[edit]

| जाति पाति पूछे न कोई | हरि को भजे सो हरिका होई || |

Let no one ask a person’s caste or with whom one eats; devoted to Hari, one becomes Hari’s own. |

This was declared by Ramananda (c.1400–c.1470), the pioneer of the medieval bhakti movement in north India. He belonged to the lineage of Ramanuja[2] and lived a life of self-surrender and dedication. Once he went on a pilgrimage to south India. On his return, his companions refused to admit him into their fold, arguing that he might not have adhered to strict rules regarding food and other rituals during his long absence. This was a rude shock to him. He came out of the fold and became a liberal advocate of bhakti, and practiced severe austerities at the Panchaganga Ghat in Banaras. According to him, Sri Rama was the Supreme Spirit and humanity was one big family.

Kabir (1440–1518) was the adopted son of a poor Muslim weaver couple, Kabir was not bound by strict rituals or religious discipline, which made him an unconventional poet and mystic. His life centered on Kashi. He could not formally claim anyone as guru because of his humble origin, but was drawn to Ramananda’s teachings. One day while Ramananda was going down the ghat for a bath in the Ganga, his foot touched a human body in the darkness. Startled, he exclaimed, ‘Ram, Ram.’ Immediately, Kabir got up and with folded hands announced that, since he had given him the Ram-mantra, Ramananda had made him his śiṣya—regardless of his religion. He also told him about his yearning to reach God. A pleased Ramananda accepted him as disciple.

Kabir was a saint of the masses. His simple compositions—dohas, couplets, and chaupais, quatrains—go straight to the heart, are easy to remember, and have remained immensely popular, enabling people to grasp the essentials of a simple and profound life in the spirit. His admonitions remain equally popular:

|

माला तो कर में फ़िरै, जीभ फ़िरै मुख माही| |

The rosary keeps moving in the hand, the tongue in the mouth, and the mind in all four directions; this surely is not remembrance. |

Guru Ravidas (c.1398–c.1448) was born in the cobbler community and was popularly known as Raidas. He was a firm believer in karma. He did not worship any particular deity, believing in the one and only omniscient and omnipresent God:

|

कृष्ण करीम राम हरि राघव जब लग एक न पेखा | |

Krishna, Karim, Ram, Hari, and Raghav—when none of them have been found near; and the old Vedas, rules of conduct, and Quran are none written in easy style; |

As news of this self-taught seer began to spread, people started thronging his humble abode seeking solace and advice. Conservative brahmanas of Kashi could not stand the popularity of this ‘untouchable saint’, and a complaint was lodged against him to the king on the grounds that he was working against age-old social norms. But when the king called Raidas to his court amidst an assembly of learned men, no one could match his spiritual knowledge and insights.

One legend describes Raidas as Mirabai’s guru. One of her compositions dedicated to Raidas lends credence to this belief.

Tulsidas (1543–1623) • The legend of Tulsidas’s passionate attachment to his wife Ratnavali (Buddhimati) is well known. Once when she went to her father’s place, Tulsidas followed her. Ratnavali felt shamed by his inordinate attachment and admonished him: ‘You have such fondness for this body of mine which is but skin and bones; if only you had the same devotion to Rama, you would not have had the fear of samsara.’ These words struck gold. Tulsidas abandoned home and became an ascetic. Not only was he able to redirect his attachment and convert it into bhakti, he could reach a state where he could say with the fullness of conviction:

| सीया राममय सब जग जानि | करऊँ प्रनाम जोरि जुग पानी || |

Knowing the entire world to be permeated by Sita and Rama, I join my palms and offer pranams. |

The literary excellence and popularity of his Ram-charit-manas, the Hindi rendition of the Ramayana, led Nabha, the author of Bhaktamal, to suggest that Tulsidas was Valmiki reincarnated. Tulsidas’s devotion to Rama found further expression in nearly a dozen works, including Vinay-patrika, Dohavali, Kavitavali, and Gitavali.

He spent a good portion of his life in Varanasi, where he passed away at Asi-Ghat.

Saints of Modern Times[edit]

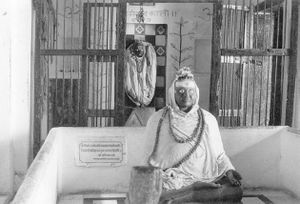

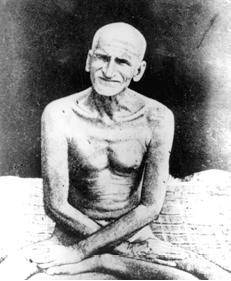

Trailanga Swami (c.1607–1887), famed for his yogic powers, is easily the most well-known of modern saints who lived at Kashi. Having met him at Manikarnika Ghat, Sri Ramakrishna described him thus: ‘I saw that the universal Lord Himself was using his body as a vehicle for manifestation. He was in an exalted state of knowledge. There was no body-consciousness in him. Sand there became so hot in the sun that no one could set foot on it. But he lay comfortably on it.’ He is reputed to have lived for nearly 280 years, over half of which he spent at Kashi. He freely roamed the streets, living sometimes at Asi Ghat or Dashashwamedha Ghat, at other times at the Vedavyasa Ashrama at Hanuman Ghat, and finally on a huge block of stone in the open courtyard of Mangal Das Bhatta’s small home at Panchaganga Ghat. He could read people’s minds like books, and drank poisonous liquids by the bowlful without dying. Once he was put in jail for violating city laws. Soon he was found walking on the jail roof. The truths of the scriptures about God-realized souls were clearly manifest in his being.

Swami Bhaskarananda Saraswati (1833–1899) was also reputed for his austerity and saintly character. Getting deeply interested in spiritual life when he was only eighteen, he travelled all over India as a wandering monk for many years. But, ‘even though I practiced such austerities, I gained very little; ignorance and sorrow were as deep as ever. Finally, [in 1868], I sat down here in this garden [Anandabag,near Durga Mandir] and resolved, “May God be realized or may this body die.” Now, you see, I get a little abiding bliss.’ He too was reputed to have yogic powers, and had foreseen his own death. Though his influence spanned all sections of society, the transformation of character of several notorious pandas wrought by his influence is especially worth mentioning.

Swami Karpatriji (1907–1982) is a more recent figure who, renouncing family and all material luxuries,

set out on his quest of the Unknown at the age of seventeen. Later he became a preacher of religion and did pioneering work in safeguarding the Indian tradition, having established the Dharma Sangha in Kashi for this purpose in 1940. He also published a Hindi daily Sanmarg, which reflected his religious and political views, and composed various books in Hindi, including Vichar-piyush and Ramayan Mimamsa. Karpatriji truly was knowledge, action, and devotion personified.

The Literary Tradition[edit]

Bhartendu Harishchandra (1849–1882) is known as the father of modern Hindi literature. A poet, dramatist, journalist, and critic, he successfully brought about the transition of Hindi from the medieval tradition (rīti) to the modern era. His writings are marked by remarkable realism and capture ‘the agonies of India: unrest of the middle-class, hopes and aspirations of the youth, and urge for progress and removal of injustice’. He was also a social and religious activist, an accomplished actor, polemicist, and wit. The Kavi-vachan-sudha started by him in 1867 was the first journal published in the Hindi language. He followed it up with the Harishchandra Magazine (later called Harishchandra Patrika), and the Balbodhini Patrika. He was conferred the title ‘Bharatendu, moon of India’ by his fellow Banarasis for his remarkable achievements.

Jaishankar Prasad (1889–1937) is credited with initiating the chhayavada movement in modern Hindi literature, characterized by romanticism, mysticism, and symbolism. Prasad is especially known for his prose writings, though Kamayani, an allegorical epic poem on Manu, is regarded by many as his best work. Apart from being a poet, he was also a philosopher, historian, and sculptor. His writings are an exquisite blend of art, philosophy, and history.

Munshi Premchand (1880–1936) is the penname of Dhanpat Rai, one of the greatest literary figures of modern Hindi and Urdu literature. Having lost his parents at a very young age, he faced poverty and struggle early in life, and these remained with him till death. His stories and novels reflect the harsh realities of life.

Premchand inaugurated the genre of fiction and made the short story a legitimate literary form in Hindi literature. His stories make a moral point or convey deep psychological truths. He was also active in the Swadeshi movement. In fact his very first collection of stories, Soz-e-Watan (Dirge of the Nation), was labelled seditious and destroyed. The first story of this anthology was ‘Duniya Ka Sabse Anmol Ratan, The Most Precious Jewel in the World’; and this was ‘the last drop of bloodshed in the cause of the country’s freedom’.

Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya (1861–1946) was a great patriot, eminent educationist, renowned journalist, prominent social and religious reformer, erudite scholar, able parliamentarian, and eloquent speaker. A giant among men, Pandit Malaviya not only helped lay the solid foundation of Indian nationalism, but also worked tirelessly, year after year, to build—brick by brick and stone by stone—the noble edifice of India’s freedom. He was one of the few individuals to become the president of the Indian National Congress thrice: at Lahore (1909), Delhi (1918), and Calcutta (1933). Among his many achievements, the Banaras Hindu University stands out as a lasting legacy. The university came to be known as the ‘capital of knowledge’ even in his lifetime. He chose Banaras as the site for this university ‘because of the centuries-old tradition of learning, wisdom, and spirituality inherent to the place. His vision was to blend the best of Indian education culled from the ancient centres of learning—Takshashila and Nalanda and other hallowed institutions—with the best tradition of modern universities of the West.’ And in this he was remarkably successful.

The Tradition of Music[edit]

In the words of Swami Vivekananda, ‘Music is the highest art and, to those who understand, is the highest worship.’ Banaras has its own rich and unique history and tradition of music. Shiva is the presiding deity of Varanasi; and he is the master of dance and music. According to legend, apsaras, gandharvas, and kinnaras have lived in Varanasi and contributed to its rich musical tradition.

The Buddhist Jatakas have many examples of highly talented courtesans with special talent in music and the arts. This tradition of music continued right down to the modern-day kathaks (hereditary musicians) and tawaifs (courtesans). The medieval Bhakti movement contributed greatly to the development and popular dissemination of religious singing and music. The bhajans of the medieval saints remain immensely popular.

| The Banarasi culture held a special meaning, especially for those who were nurtured by it. It symbolized a way of life, characterized by the twin features of mauj |

[enjoyment, conviviality, festivity] and masti [contentment, serenity, buoyancy, heartiness, and even recklessness]. … There was yet a third aspect that had a balancing effect on this mauj and masti that we shall call anasakti, or a detached outlook. Thus, while sipping honey from the flower of the jovial and ever festive City, it was not unusual for Banarasis to withdraw from their gay environs and become otherworldly. In fact, this other-worldliness is so strong, so palpable, so nearly tangible in the ethos of the City, that it may have been almost impossible for Banarasis to remain insensitive to this underlying spirit of the place, and consequently, get lost in worldly enjoyments. |4=Varanasi at the Crossroads, 718–9.}}

Many reputed gharanas or schools of music developed in Banaras over the last few centuries. These included the Senia (from the lineage of the illustrious Tansen) and Mishra (Prasaddhu-Manohar) gharanas in vocal music, Ramsahay gharana in tabla, Badal Mishra gharana in sarangi, and the gharanas of Mian Vilatu and Nandalal in shahnai. The nawabs of Awadh, the rajas of Kashi, and many other rajas and nobles who settled down in Kashi patronized music and the arts. Many musical styles— Dhrupad, Khayal, Dhamar, Dadra, Hori, and Kajri, among others— flourished in the rich environment of Banaras.

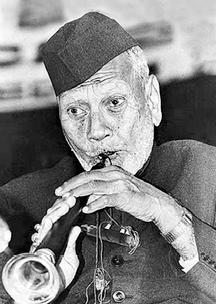

Banaras has produced a galaxy of great musicians who are revered as legends in their own right. Ustad Bismillah Khan, Pandit Kishan Maharaj, and Girija Devi are three famous names of recent times.

Qamaruddin, famous as Bismillah Khan (1916–2006), spent his childhood in Varanasi, where his uncle was the official shahnai player in the Vishwanatha temple. He not only introduced the shahnai to the concert stage with his recital at the All India Music Conference at Calcutta in 1937, but also single-handedly took it to world renown. He received honorary doctorates from Banaras Hindu University and Vishwa Bharati University and in 2001 became only the third classical musician to be awarded the Bharat Ratna, the highest civilian honour in India. Despite receiving such acclaim, he always remained his simple self. He believed that ‘musicians are supposed to be heard not seen’. In his last days he turned down requests from the central and state governments for treatment elsewhere, as he would not leave his favourite Banaras.

Padma Vibhushan Pandit Kishan Maharaj (b.1923) is one of the most renowned, respected, and admired tabla players of our times. Trained by his father, Pandit Hari Maharaj, and his uncle, the famous Pandit Kanthe Maharaj, he has dominated the world of Indian classical percussion in a career spanning more than fifty years, evolving his own style with its highly skilled layakari (perfect timing). He has been a versatile accompanist to a variety of genres of classical music and dance. He is also known for his talent for improvisation during performances, introducing the most complex tālas (beats) with odd numbers of matras (notes).

Girija Devi (b.1929) was born in a music-loving family of Varanasi and was initiated into music at the tender age of five. Known as the leading exponent of the Banaras gharana of thumri, Girija Devi has an amazing proficiency in a wide range of Hindustani vocal music: khayal, thumri, dadra, tappa, kajri, hori, chaiti, and bhajan. A recipient of the Padmabhushan and Sangeet Natak Akademi awards, her care for students is reflected in her successful career as a guru for over a decade at the ITC Sangeet Research Academy, Kolkata.

Swami Vivekananda once said, ‘Art, science, and religion are but three different ways of expressing a single truth.’ The saints, sages, and savants of Varanasi verily express that single truth in their own inimitable style. The resultant melody is vibrant Varanasi, the city of Shiva.

Related Articles[edit]

Notes & References[edit]

- Originally published as "Varanasi" by Prabhuddha Bharata October 2007

, November 2007

and December 2007

editions. Reprinted with permission.