Daoism and Hinduism

“Taoism has borrowed heavily from Hinduism, and from an early age Taoist mystics have identified Kunlun with Meru.” - Lee S. Mong[1]

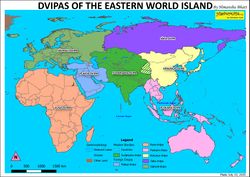

While the Han Chinese call their country Zhōngguó, the lands in general to the east of the Himalayan Range were known in both Sanskrit and Persian literature as 'Cheen', and this word was then adopted by explorers that visited India [and possibly more eastwards.] In Sanskrit scriptures, both Hindu and Jain, the continent on which eastern China (Tibet is on the same continent as the Indian Plateau) resides is called 'Krauncha-dvipa'.

The interchange of ideas between Daoists and Aryas was common in China, but even some in India knew of Daoist ideas. Indian monk Su-t'o-shih-li arrived to China when he was aged 85 is known to have been an expert on the Hua-yen Ching and is shown in the Fo-tsu Li-tai T'ung-tsai as a 208yo master of incantation[2] (i.e., he was a Tantrik.) In displays, the most important Daoist scholar, Lao Zi [who either founded or systemized Daoism] is shown riding on a black buffalo westwards towards Shou Shan (Taoist paradise) for acquiring Bauddh [not Daoist] doctrines![3]

The history of Bauddh missionaries into Han Chinese lands and even advising the emperors is well-recorded but perhaps the earliest encounter between missionaries from India and a Han Chinese monarch is in the reign of King Mu. As the Daoist Lieh-Tzu text of Lie Yukou states, "During the years of King Mu (b.c. 1001-495) of the Chou Dynasty (b.c. 1122-255) some miraculous people came from the Extreme West (i.e., India), who could turn hills into rivers, rivers into hills, transform cities and towns, enter into water and fire, go through metal and stone, and could perform thousands of other wonderful things without exhaustion. The King respected them as saints and built a Middle-Sky-Paradise to accommodate them."[4]

Religion and Philosophy[edit]

Both Daoism and Hinduism are a religion and a philosophy. Religious Daoism is Daojio, while philosophically it is Daojia. Hinduism's philosophical side is studied as a darshana (metaphysical worldview).

Creation Myth[edit]

In the Daoist story written by Xu Zheng in his Sānwǔ Lìjì (Three Five Calendar), a cosmic egg split open, within which came out Pangu, and he separated chaos from order, Earth from heaven - yin from yang. Pangu was the first being to have lived in the universe and when he died, his bodily components parts of the universe. This is similar to the Puranic stories of a cosmic egg, and its embryo became Brahmā Prajapati. One version is that Ishvara became Swayambhu who entered into the egg It created. Once the egg hatched, and its top portion became the heaven and the bottom half the earth. The Pangu-story also bares resemblance to a Tibetan Bonpo creation story wherein Kuntu Zangpo made the universe from breaking an egg.

His breath into wind, voice into thunder, left eye the sun, right eye the moon, 4 limbs and body the mountain and lands, blood became rivers, veins and muscles became paths and roads, flesh and skin into fields and lands, and hair into stars.[5] Further, his other skin and his tissue became grass and trees while teeth and bones became gold and rocks, the marries became pearls and jade, and sweat the rain. Then as the wind blew onto Pangu, the mites and fleas on his body became humans. This story is like the Hindu story of the Purusha that sacrificed himself for the creation of the universe from its body.

Universal Principle[edit]

Both Daoism and Hinduism believe in a universal principle of ethics. In the former that is known as Ganying and in the latter, Rta. When people act ethics, they are said to have acted in accordance with Ganying or Rta.

Dualism[edit]

Reality is classified with a dualistic outlook, such as ethical vs. unethical, life force vs. mortality, soul vs. matter.

Whereas in Daoism dualism is illustrated using the yin-yang symbol, in Hinduism (especially in Tantrism) it's shown using the shatkona (its top part is masculine energy and bottom is feminine energy.) Essentially, they demonstrate harmony between opposites. Whereas the harmony in Daoism is known as Wuji, in Hinduism it's known by terms like avyaktam and yamala (Union of Shiva and Shakti.)

Basically, dialectical monism is an approved worldview by both religions. The oldest Hindu metaphysical worldview (darshana) is known as Samkhya, in which the reality comes down to purusha vs. prakriti.

Pluralism[edit]

Daoism and Hinduism are not exclusivist that require absolute adherence, and their pluralistic natures can be seen among followers that are open to practicing spirituality in different environments and are always encouraged to seek the divine anywhere. For example, many Daoists claim to belong to another religion (i.e., Buddhism or animism) while many Hindus likewise explore different spiritual environments and practices, such as praying in different establishments.

Ultimate Reality[edit]

The Dao like the Brahm is a good force pervading the entire universe. Zhuang Zi used the term 'Zaowuzhe' (Creator) for the Dao in his works. Daoists aim for Cheng Dao (obtaining the Dao) like how Hindus aim for Brahmyukt (union with Brahm or Moksha.) Scholar of scientific philosophy and a systems theorist, Ervin Laszlo describes the Dao as a “voided reality” and then says the concept of Brahm is the same.[6]

“Does this not remind us more forcibly of Rta and Brahman, qi and the Dao, than the modern Western God?”[7] - By Karen Armstrong

Theology[edit]

How Daoists envision the Dao being composed of as 3 aspects is similar to the Hindu trinity which has been theorized but is not official in canon.

Worship[edit]

Many Daoists worship the Dao, as well as other gods, including wherein worshippers accept their deities as manifestations of the Dao. For example, Lao Zi is considered by many Daoists to be such. This is parallel to how Brahm in Hinduism is worshiped by praying to a particular person (i.e., Krishna) as ishta-devta or as an avatara of Brahm.

Sacredness of Ecology[edit]

- See also: Environmentalism

"In Dao De Jing and works by Zhuangzi, not just every person, but every entity—including human beings, animals, plants, rivers and mountains, even a rock—is equal before Dao, because they come from the same source, Qi."[8] - Dan Dombrowski and Brianne Donaldson

In Daoism, everything that is living possesses qi (or chi.) Sometimes even mountains are thought to contain it. Zhuang Zi, the 4th century CE Daoist master, presents the idea of a union with nature[9], and he discusses nature often. Daoists seek this union with nature.[10] The ultimate goal for Daoists is to return to the primordial oneness of Dao, or the way of nature. They employ a number of metaphors to express this union with nature.[11]

Common Sacred Mountains[edit]

The biggest legend in Han Chinese culture is that of Xi Wang Mu, a goddess-queen that resides atop a mountain along the Kunlun Range. The Shangqing school of Daoism had elevated her status. She was first mentioned by literature in the Shanhai-jing (Classic of the Mountains and Seas) from the 4th century BCE. Malaysian-born Chinese Professor Chung Tan[2] lived India as a scholarly specialist of Sino-Indian relations and he believed that Xi Wang Mu was actually Uma (Parvati) and that Mt. Kunlun was actually the Himalayas.[12] After visiting by Mt. Kailash and Lake Manasarovar, he wrote that he "had the honor to pay homage to Goddess Xiwangmu/Uma."[13]

According to Chinese literature, she met with Lao Zi as well as some emperors of eastern China, and she was seen riding on a cloud-carriage with 50 Celestial Immortals (Tianxian) at a jade-coloured mountain (Yushan) which had the Peach Tree of Immortality[14] on the mountain and a Gemstone Pool (Wangmu Chi) related to a Sweet-wine Spring (Li Quan) at the foot of the mountain.

Her epithets include 'Turtle Mountain Gold Mother', 'Turtle Station Gold Mother', 'Golden Mother of the Tortoise', 'Golden Mother Yuan Jun', 'Xichi Gold Mother', 'Gold Mother', 'Yao Chi Gold Mother', 'Jade Mother', 'Jade Goddess', 'Yao Chi Old Mother', 'Metal Mother', 'Immortal Mother', 'Queen Mother' and simply 'Mother'.

- Xi Wang Mu's Ethnic Identity

Because she is affiliated so heavily with turtles and is called 'Golden Mother of the Tortoise', she was likely of the turtle gotra (totem), which seems to have had prominence around her mountainous region. This gotra was known as either Kashyapa or Kurma in Hindu sources, and exists still today among Indians. Nearby there is the region of Kashmir, that's etymology is 'Kashyap-Mir' or Turtle Mountain. Mentioned in this article below is Manjushri, a Kashmiri Bodhisattva, who is also affiliated with a turtle tribe.

Because Han Chinese emperors have met her in different eras far apart, Xi Wang Mu could not have been an individual but a position of a chieftain, just like how the Hindu Divine Council of 33 was succeeded across generations by 33 members who held the same titles as the original conference. Her being a chieftain can be seen by her title 'Queen'.

- Chinese Mt. Yushan is Indian Mt. Mandara

There is no question about it that the Arya scriptures' Mandara mountain is the same as Turtle Mountain of Chinese folklore. Firstly, this mountain in Han folklore[15], such as Ch'u Yuan's T'ien Wen, was upheld by a turtle. In Hindu scriptures, too was it upheld by a turtle (Kurma.) In Han legends it had a Peach Tree of Immortality. In Hindu scriptures too it was said to have a tree named Kadamba with long handing branches, and it acts as a chaityapadapa. Even the Churning of the Lake, the tug of war between Devas and Asuras took place atop Mandara mountain, in which the 2 sides competed to win the elixir. Furthermore, like how Han mythology's mountain is associated with gemstones, in Hindu scriptures, from the tug of war between the 2 sides came 14 jewels, and the mountain had several gems lying around it[16]. As the very mountain is called 'Jade Mountain', the colour of it would be a green hue. This is in conformity with Bauddh sources of Mandara being a green mountain in Karmapa Tekchok Dorje's Shrīchakrasambhāra Tantra and author Geshe Kelsang Gyatso. In Han Chinese mythology this mountain produced jade gemstones, as is seen in the 6th century CE poem Thousand Character Classic, which states "Gold is born in the River Li; jade comes from Mount Kunlun."

- Mt. Kunlun Does Not Mean Entire Kunlun Range

That the Kunlun affiliated with Xi Wang Mu is a particular mountain or 2 and not the entire Kunlun Range (Xi Shan Jing) is noticed not just in the folklore stating but also specifically by the Hai Guo Jian Wen Lu that establishes, "Kunlun does not refer to the Kunlun Mountains around which the Yellow River flows." He continues, "In the south of Qizhouyang (literally "sea of seven islands," the sea area of the Xisha Islands) there are two towering mountains, one named Dakunlun (Greater Kunlun) and the other Xiaokunlun (Lesser Kunlun.)" This Greater Kunlun is Mt. Sumeru while Lesser Kunlun is Mt. Yushan. Yushan mountain has been called 'Shao Guang' in the Zhuang Zi, and in other texts as 'Kameyama' or 'Guishan' (Tortoise Mountain), and 'Hua'. The specific person of this tribe the mountain was named after is perhaps Nen-wo-shë, who is said in Chinese legend to have but off 1 of his legs to balance for holding the 4 extremities of the world.[17]

- Location of Jade Gate Pass

It is believed that even Lao Zi had also passed through Jiayuguan and the Jade Gate on his way to the Western Paradise. On the inside of each gate are horse lanes leading up to the top of the wall. Modern-day Lanak La is the Jade Gate Pass.

- Location of White Jade River

The Jade Mountain is mentioned the origin of 4 rivers of which the Jade River that is adjacent to the mountain is modern-day Yurungkash, which is officially also recognized as the White Jade River. In Bauddh mythology, from Manjushri's head there came out a golden tortoise, and it entered the Sitā-sara River (Yurungkash), and from a bubble there came forth two white tortoises, male and female. 'Golden tortoise' is a common theme in this region of the Tibetan Plateau for both Han Chinese and Indian sources.

- Location of Liusha

The Hai Ching states that her jade mountain was "beyond the Kunlun" mountain range and to the west of the Liusha (Moving Sands) desert. This brings us to the Ladakh region. The eastern part of its Askai Chin region is literally a desert where no vegetation grows. The Book of the King of Huainan authors write that Xi Wang Mu lives by the Liusha desert where originates 1 of 4 rivers. The Liusha-he mentioned is specifically a waterbody within the Liusha desert.

We can even find a reference of the desert in the travels of Hwui Seng. After Hwui Seng and Sung Yun with their crew moves west of the Chih Ling (Barren Ridge of N.W. Tibet), and the cross the Drifting Sands to arrive at the country of the To-kuh-wan (Eastern Turks), begins proceeding westwards to Shen-Shen.[18] To-kuh-wan is today called Baltistan. Shen-Shen is Shenaki (Dardistan.)

- Location of Yaochi

The Wangmu Chi is likely the same as the the Yaochi (Turquoise Pond) of texts like the Mu Tianzi Zhuan mention. Modern Shu Lungspo Thang is this pond and it is connected to the mountain via a branch of the Lakhta Lungpa river. Wangmu Chi is also most likely the same as Liusha-he (AKA Shahe.)

A passage from the Shanhaijing states that Mt. Kunlun was located to the south of the West Sea, on the shore of the Liusha-he, behind the Red River and in front of the Black River. This Red River is the modern Qizil Jilga (Turkic for Red Valley[19]), east of Mt. Bei Tip. The Black River is the modern Karakash River - it's stream comes near the western side of Mt. Bei Tip. The Liusha-he is the body mentioned below.

- Location of Yushan

The first tier of Kunlun Mountain was Liangfeng Dian (Cool Wind Mountain.) Anyone who climbed it would receive immortality. The second tier was called Xuanpu Tang (Hanging Garden), where the Goddess has her Yingzhou (Twelve Palace.) Modern Mt. Qortantan (5567m) is the first peak while Bei Tip (7912m) is the second. There was said to be a 3rd peak called Shangtian (Ascending Heaven) on which resided the Great Emperor (Taigi.) Those who ascend the 3 peaks are believed to become 'ling' (numinous) with the power to control wind and rain, and 'shen' (divine) in that order.

Shakra (Indra) is sometimes identified with the Taoist 'Jade Emperor' who has these powers and resides atop the mountain. Historically, some of the persons who held the position of Indra within the Divine Council of 33 would not have been a stranger to Mandara. One of them had obviously partaken in the Churning of the Lake. As Chinese Bauddh stories mention a monkey tribesman named Sun Hsing-che (AKA Sun Wukong) meeting Xi Wang Mu, it presents the idea that the 2 lived nearby, especially as when the armies of the latter laid siege to the former's mountain (Hua-kuo Shan) from the southern gate of Yushan. Hua-kuo Shan was said to be the home of the monkey tribe in the Bauddh story.[20] Certainly, as the Valmiki Ramayana illustrates, Hanuman's Kishkindha is in Kashmir, modern-day Bandipore district. The Vanara (Monkey) tribe to which Hanuman belonged would have also lived in adjacent areas, which would include Ladakh. Xi Wang Mu is also described as having 3 birds that collect food for her, and 1 in particular, Xing Niao, was her personal messenger. These "birds" were persons of the Garuda-Kinnara gotra just as in Arya literature, they are known for traveling. In fact, the second name of the Tibetan Plateau in Hindu scriptures is Kinnara-varṣa. Even Tibetans wrote of the 'Garuda Valley' being around the Sutlej River in Tibet. They further wrote of the Zhang Zhung Kingdom's capital as 'Khyunglung Ngulkhar' - Silver Palace of the Garuda Valley. Like how Tibetans described Tonpa Shenrab riding a Garuda, Xi Wang Mu is described riding a 'fêng huang', which may be the same person as Xing Niao. The Daoists have also written in texts not associated with Xi Wang Mu of niao xing metaphorically describing a wandering man as 'a bird in flight that leaves no trail behind'.[21]

Sharing of Alchemy and Medicine[edit]

Shanmuga Velan stated that saints Bogar (also called Pokar) and Pulippāņi were natives of China and they came to Tamilnad about 1,600 years ago from his time, and they joined the Siddhars' school. Bogar has his samadhi in modern Tamilnad[22] but in his time he did visit China and taught what he learned from his master Siddhar Kalanginathar, who was also from China but learned and practiced siddhar science in Tamilnad. Kalanginathar's master was Tirumular. Upon Kalanginathar's dying request, Bogar taught siddhar science in China.

Inner Energy[edit]

Lung is a Tibetan name for the subtle energy which in Sanskrit is called prana and in Chinese chi (qi.)[23] - Dmitry Ermakov

Related Articles[edit]

- Hindu Mythology Explained

- The Spread of Hinduism into China

- History of Ancient Geography

- Olmo Lungring is in Karakoram

- Yama's Kingdom is in Kashmir

- Varaha's Khetra is in Kashmir

- Ravana's Lanka is in Kashmir

- Hanuman's Kishkindha is in Kashmir

- Zarathustra was born in Kashmir

- Modern identification of Rig Vedic rivers

- Kingdoms of Asura Dominance

External Resources[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ P.21 Understanding Jade: A Layman's Guide By Lee S. Mong

- ↑ P. 151 China Under Jurchen Rule: Essays on Chin Intellectual and Cultural History By Hoyt Cleveland Tillman and Stephen H. West

- ↑ P. 179 Illustrated Dictionary Of Symbols In Eastern And Western Art By James Hall

- ↑ P. 128 Rabindranath Tagore Birth Centenary Celebrations Proceedings of Conferences · Volume 3 By Sunilchandra Sarkar

- ↑ P. 12 East Meets West By Joan Chan

- ↑ What is Reality? The New Map of Cosmos, Consciousness, and Existence By Ervin Laszlo

- ↑ Sacred Nature Restoring Our Ancient Bond with the Natural World By Karen Armstrong

- ↑ P. 92 Beyond the Bifurcation of Nature A Common World for Animals and the Environment By Dan Dombrowski and Brianne Donaldson

- ↑ P. 7 The wisdom of Zhuang Zi on Daoism: Zhuang Zi By Zhuangzi

- ↑ P. 245 Fifty Eastern Thinkers Diane Collinson, and Kathryn Plant, Robert Wilkinson

- ↑ P. 99 Berkshire Encyclopedia of Sustainability: The spirit of sustainability By Willis Jenkins and Whitney Bauman

- ↑ P. 54 Himalaya Calling: The Origins of China and India By Chung Tan

- ↑ P. 24 China: A 5,000-year Odyssey By Chung Tan

- ↑ When Xi Wang Mu gave Wu-ti, the Han Dynasty's Emperor, he was anxious to bury it for growing more but the goddess informed him that Chinese soil was not suitable and that the tree bloomed only once in 3,000 years;

P. 473 Britannica Encyclopedia of World Religions By Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc - ↑ Yi'nan tomb in Shantung dating from the 2nd century CE, on which there's a carved picture of a tortoise holding a 3-tiered mountain in Wu Hung;

P. 213 From Deluge to Discourse: Myth, History, and the Generation of Chinese Fiction By Deborah Lynn Porter - ↑ "It was big and exceedingly lustrous. Many gems were [lying scattered] all round. It had many trees such as sandal tree, Parijata, Naga, Punnaga and Champaka. It was full of various kinds of animals and deer, lions and tigers." [67-68][1]

- ↑ P. 1468 Chinese and English Dictionary: Containing All the Words in the Chinese Imperial Dictionary, Arranged According to the Radicals By Walter Henry Medhurst

- ↑ P. 157 The India They Saw Foreign Accounts · Volume 1 By Sandhya Jain

- ↑ P. 117 Trade and Politics in the Himalaya-Karakoram Borderlands By Deba Prosad Choudhury

- ↑ P. 69 The Hsi-Yu-Chi A Study of Antecedents to the Sixteenth-Century Chinese Novel By Glen Dudbridge, Shaw Professor of Chinese Glen Dudbridge

- ↑ "Niao xing er wu ji";

P. 4 Absence: On the Culture and Philosophy of the Far East By Byung-Chul Han - ↑ Bogar’s Samadhi is to be found in Tamilnad’s South West corridor at the Muruga shrine of Dhandayuthapani Temple, Palani.

- ↑ P. 520 Bø and Bön: Ancient Shamanic Traditions of Siberia and Tibet in Their Relation to the Teachings of a Central Asian Buddha By Dmitry Ermakov