Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche

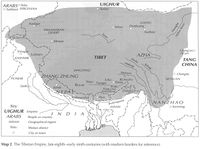

Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche is the most important person of Yungdrung Bon, being one of the Four Sugatas or Transcendent Lords, the other 3 being Sangpo Bumtri, Satrig Ersang, and Shenlha Okar.[1] Hinduism in Tibet began with the Bon religion preached by Tonpa Shenrab, born Mura Tahen[2]. He is noted in Bon scriptures to have come from a western land called Olmo Lungring, in its royal Shenyi Podrang,[3] and wandered into to Zhang Zhung.[4] In Tibetan, Shenrab's country is also called sTag-gzig, Shangri-La, and Shambhala. Like several other rishis, such as Rishabha, Ravana, and Śukracharya, Tonpa too meditated at Mount Kailash.

According to most Bon sources on Guru Shenrab's dating, he arrived in Tibet either around 18,000[5] or 16,000 years ago. According to another Bon tradition he was a contemporary of the pre-8th century Zhang Zhung king Triwer Sergyi Jyaruchan.[6] However, the present day Tibetan history scholar and Dzogchen master Chogyal Namkhai Norbu calculates the probable actual date of his birth as 1917 BCE.

What brought the prince to the region was his quest to retrieve his 7 blue horses that were stolen by his aggressor Khyab-pa Lag-Ring and taken to Kangpo in Zhang Zhung. Earlier Khyab-pa had kidnapped Shenrab's daughter, which Master Shenrab rescued mounted on a Garuda.[7] Master Shenrab went forth with his four attendants to find them. During his time in Zhang Zhung, he taught the locals, 24 masters in number according to the Zhang Zhung sNyan-brGyud (Secret Oral Lineage of the Dzogchen Zhang Zhung), the basic tenants of Bonpa Dharma. He landed in Kongpo where battle ensued and he captured the father of Khyab-pa, Gyala Dorje. Khyab-pa then surrendered, Shenrab was then given back the horses, and Khyab-pa became his pupil.[8] They left Tibet to return home and at age 32 Prince Shenrab decided to give up the royal life and take solitude (sanyasa) to become a monk. Khyab-pa had become his leading disciple.

At age 82 he departed the world and attained Mokṣa. Both in his country and among the locals in Zhang Zhung, Buddha Shenrab was successful in stopping ritual animal sacrifices. Bon preachers continued visiting Tibet for further propagating the religion, and many Tibetan Bonpas visited Olmo Lungring for learning the religion and meeting with Bonpa scholars.

There are two types of Bonpas classed by Buddhists:

- White Bon - They are the ones who also follow Buddhism.

- Black Bon - They are strictly Bonpas.

In his native language, Musang sTag-gzig, the religion is known as Drungmu Gyer, in Tibetan as Yungdrung Bon (Eternal Religion) or as Bonpo, and in Sanskrit as Swastika Dharma. The Bon religion became so popular in parts of India outside of Olmu Lungring that at one point, several Indian Bon scriptures were translated into Tibetans in 8th century CE by Vairocana of Pagor.[9] According to the Secret Mother Tantra, the religion was known between the Eternal Gods, who then preached it in Sanskrit to the 33 gods[10] on Mt. Meru (Ti-se), which is considered the ultimate centre[11]. Then the sky-goer goddess Zangza Ringstun preached it to gSang-ba 'Dus-pa[12] in sTag-gzig.[13]

Background[edit]

Lineage[edit]

He was of the dMu-gShen Dynasty of Olmo Lungring[14] from the lineage of King dMu-rigs Phrul[15]. dMu refers to his clan, and gShen to his linguistic nationality. dMu means sky.[16] The 6 royal clans of regional importance from Shenrab's era were dMu, Hos, dPo, Shag, rGya, and gNyan, of which the prior 3 were of Shenrab's country.[17] rTsa rgyud nyi sgron is the Tibetan Bonpa work that elaborates on Master Shenrab's lineage.[18] His father Sogya was the descendant of two different lineages; dMu from his father's side and Phywa from his mother's.[19] Shenrab's father had the surname Tog-dkar, a name that has much significance for Gautama Buddha[20] and Svetaketu[21] are also named as such. According to Bdhad-mdzod[22], the men and women who descend from the gods have for their ancestor Srid-pa Ye-smon rGyal-po. The 3 clans descending from him and his wife Chu lCam are the Phywa, dMu, and gTsug.[23] The etymology of his name is that 'gShen' means heavenly, 'rap' is supreme one, and 'Miwo' is great man.[24] Also ‘gShen’ is assumed to mean heavenly, it’s actually been an untranslatable word.[25] That is because it isn’t a Tibetan word. It’s a word in Shenrab’s own nationality, gShen.

It’s even used synonymously with ‘Bon’ and ‘Bonpo’, like how ‘Shakya’ has been used by Bauddhs patronymically to describe a practitioner of Bauddh Dharm.

The name Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche itself is a title. He is also known as gSal-ba. 'Shenrab' is a patronymic title stemming from the gShen[26] ethnicity. Even in the modern era, the princes of the Shins claim the title 'Shin Ra', which is related to a person in legends known as Heaihen Shin Raji or Shiribadatt. His larger title is Tonpa Shenrab Kunlas rNampar rGyalba (The Teacher Shenrab, the Lord of Man, the Conquerer'.')[27]

Royal life[edit]

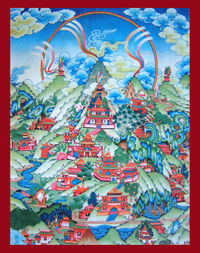

The inner division of the royal premises made up of eight "islands"[28] surrounding the imperial palace on the mountain Yungdrung Getseg-ri, Barpo Sogyed. To the west and north of the imperial palace, his wives lived in a castle. To the east was a the Shampo Lhatse temple.[29] Shenrab himself lived in Pho-gling-mo-gling (Father Island Mother Island.)[30] The intermediate region consists of twelve cities, four of which are towards the cardinal directions.

Family[edit]

In total he had 6 wives, 8 sons and 2 daughters.

Shenrab was married to Hoza Gyalmed ma, who is also worshiped by many Bonpas. His other 5 wives were dBo-tza' Thang-mo, gSas-bza' Ngang-ring, Phya-bza' Gung-drug, sTong-bza' Khri-lcam, Gya-bza' 'Phrul-sgyur.

The story of how he married sTong-bza' Khri-lcam relates to when he was in a battle with King Kongje Karpo of Kongpo, a Mara-demon who, with his army, shot poison-tipped arrows at Shenrab who transformed them into flowers. From seeing this, Kongje Karpo believed that Shenrab truly was a saint and he learned the Bonpa Dharma from Tonpa, and offered him to marry his daughter sTong-bza'. From the marriage, Tungdrung Wangden was born, and he is considered as the original ancestor of the Shentshang (Family of Shen) lineage in Tibet.[31]

His daughter Shensa Nechung, who was the wife of his chief disciple Khyab-Pa, gave birth to twins Sita Tabutung and Sibutung.

His 8 sons were Tobu Bumsang, Chedbu Trishe, Lungden Selva, Gyundren Dronma, Kong-tsha Wangdhen, Kongthsa Trulbu, Oldrug Thangpo, and Dungsob Mucho Demdrug.[32] Mucho Demrug worked to spread the Bon following outside of Olmo Lungring, and with his 6 disciples they traveled to Zhang Zhung and translated Bon scriptures into local languages.[33] The lineage of bShen or gShen comes from gShen-chen kLu-dga', who in turn is a descendant of Mucho and his wife rKong-za Khri-lcam. The descendants of Shenrab in Tibet are of the dMu-tsha sub-clan. Bkra-gsal-rgyal-po, was one such priest.

Ancestry[edit]

- The Legs bShad rin po che'i mdzod version

In Legs bShad rin po che'i mdzod this derivation is given.[34] From Sangs-po and Chu-lcam came 18 brothers and sisters, the oldest of whom was Srid-rje 'Brang-dkar. He and his wife lHa-bza' nGang-grags-ma had 18 male and 18 female children, the oldest of whom was lHa-rabs gNyan-rum-rje [who had been a 'Magnificent Appearence' god in his previous life.] His son was gNam-lha dKar-po, and from him came in order the 9 gNam-'then ['Then of the Sky.] The order was Kha-ye Mu-la-'then, Mu-sangs Bal-la-'then, Balsangs g.Yen-la-'then, g.Yen-sangs Phywa-la-'then, Phywa-sangs' Ol-la-'then, 'Ol-sangs Yul-la-'then, Yul-sangs dGrung-la-'then, rLung-sangs 'Od-la-'then, and 'Od-gsal dMu-la-'then. From the lighe resides of King dMu-phyug sKye-rabs appeared dMu-rgyal Lam-pa Phyag-dkar; of dMy-rgyal Phyag-dkar was dMy-rgyal bTsan-pa Gyer-Chen; Thog-rje bTsan-pa, dMy-rgyal Len-gyi Them-skas, and finally rGyal-bon Thod-'dkar (father of Tonpa Shenrab.)

- The Nyi zer sgron ma version

Shenrab's linege is known as dMu gshen lha yi gdung rgyud, and it is derived from Khor lo dbang bsgyur[35], son of dMu rgyal rigs su che ba[36] who was son of gTsug rje ' og sko.[37]

In Nyi zer sgron ma the term 'dMu' is related to dMu rje btsun po and gTsung rje 'og sko. It states that the dMu descend from dMu rabs 'then dgu, who are said to be the essence of sTag gzig.

It is written that dMu rje btsun po and Lha mo 'od gsal had four sons: dMu rgyal rigs su che ba, rJe rigs su btsun pa, Bram ze rigs su gtsang ba and rMang rigs su rdol pa. From dMu rgyal rigs the dpag pa'i mi bzhi were born, who are: Khor lo dbang bsgyur, Drum shing bcud 'thung, g.Yung drung khyim bdun and Me tog sbub gnas.

The Six Royal Clans (gdung rgyud kyi rgyal po sde drug), including the clan of gShen rab (dMu gshen lha yi gdung rgyud), came from 'Khor lo dbang bsgyur. The persons of sGa, sTag gzig and Bal po came from rJe rigs su btsun pa. The ones of rGya-gar, Phrom, and Li came from Bram ze rigs su gtsang ba. The people of Mon 'Jang and Dru gu came from rMang rigs su rdol pa. These are the dMu genealogies.

Descendants[edit]

From Shenrab and his wife Kong-za Khri-lcam came gYung-drung dBang-ldan. He had 4 sons; 'Od-kyi rGyal-po, Thog-gi rGyal-po, 'Brug-gi rGyal-po, and 'Gar-bu-chung. 'Od-kyi rGyal-po had 3 sons; dMu-bon A-pa Ru-ring, dMurje Thum-thum rNal-med, and dMu-rje rGyal, and from them descended dMu-gshen sNang mDog-can and others. Thog-gi rGyal-po's descendants reach down to dMu-shen Dran-pa Nam-mkha. 'Brug-gi rGyal-po's son was dMu-bon Yo'u-brtan, whose son was dMu-bon Thong-ltol, whose son was dMu-bon sKyes-lo-tshl, whose sons were gShen Grol-ba, dMu-kha sPo-mi-spo, dMu-kha Ye-mi-ye, dMu-le Yol-ba, and dMu-long or 'Brum-bu. In this era, the Tibetan king gNya'-khri had a son named Mu-khri bTsan-po, who was a practicing Bonpa and invited 108 scolars led by Mu-kha sPo-mi-spo and dMu-rje Yang-rgyal. These 2 gained power over death and migrated to the country of Tsong-ka. Their descendant dMu bKra-gsal Klu'i rgyal-po went to 'Dam (in gTsang) and settled at 'Bri-mtshams, then ruled over all districts. With his wife lHa-rgyan they had 3 sons; Mi-g'yo mGon-po, rDo-rje mGon-po, and dBang-phyung mGon-po. Mi-g'yo mGon-po had 3 sons; dPal-mgon-gsas (AKA Bon-gyi Srid-g'yang-babs), 'Brug-gsas, and rGod-gsas. 'Brug-gsas had 3 sons - the first 2 were called Klu-dga and Klu-brtsegs, and the younger Ge-khod.

Related Lineages[edit]

The Legs bshad rin po che'i mdzad says that dmu-gshen migrated from sTag-gzig to Zhang Zhung, and then to gTsang, while the Bru moved from Urgyan, Bru-sha, and Tho-gar. gNam-gsas-spyi-brdol was made king over Gilgit and Tokharistan, and then some of his great-grandchildren moved into western Tibet.

Linguistic Instructing[edit]

Shenrab preached in his native tongue, Musang sTag-gzig. Shenrab is described in the Rin chen gter khyim[38][39] as having brought his language to Zhang Zhung.

- Popularity of Lha'i Skad

Shenrab's previous avatar, Chi-med, however, had spoken the language of Kapita, and so the latter wrote in his native language, came to be known Yungdrung Lha (literally Yungdrung God, also known as 'Lha'i Skad' or Divine Language.) Many composers of Bonpo scriptures are said to have spoken it, 360[40] languages are said to have been translated from it, with 164 of them having been spoken in Olmo Lungring.[41] It is further said in Dragjyang these 360 languages were of the-then 1,000 existing in dZambu-ling.[42] Many times, Lha'i Skad was the original form of the Bon scriptures, from which it would be translated into Sanskrit (Sang-tri-ta), then sTag-gzig, then Zhang Zhung, and finally Tibetan.

Zhi khro rtsa 'grel quoted in Dar rgyas gsal sgron (P.641,5) says, "the Dag- pa stag-gzig was developed from Sanskrit and the latter from Kapita, the language of the gods." This means that the Intermediate language of Zhang Zhung Olmo Lungring (which is Shen) derives from Sanskrit (Sang-tri-la) while the language of innermost Zhang Zhung from Kapita. Kapita is in the Punjab[43] and has historically been a city renowned for its monastic activity.

Bon's Mother Tantras were originally in the Eternal Divine Language used by sky-goers, then in Sanskrit transmitted to Zangza Ringtsun in the land of the Thirty-three (Mt. Meru), who then translated them into the sTag-gzig Bon language and were given to Sangwa Dupa (disciple of Shenrab) in Olmo Lungring. The mantras were then taught to Milu Samlek at Rgya-mkhar Ba-chod in Zhang Zhung's Mar language, who taught them to his disciple dMu-Shen Namkha Nangwa Dogchen, who after reviewing them on Mt. Kailash bestowed them to Anu 'Phrag-thak who "three hundred and sixty great austerities," (translated them into about 360 other languages that Bon scriptures refer to) and then he finally gave them to Sad Ne-ga'u who translated them into Tibetan (Pu rGyal Bod kyi skad.)[44] Sad Ne-ga'u would then give them back to the sky-goers to protect.

- Tibetan script

Tibetan script is believed in Tibetan tradition to have come from Zhang Zhung Maryig, which in turn is believed to have come from gStag-gzig Spungs-yig.[45] The sTag-gzig script is believed by Michael Richards to have originated with the Gupta script.[46]

|

To the letter expert Yig-lha 'Phrul-bu, [the Teacher] fully explained the characteristics of the forty magic letters ['phrul yig bzhi bey]. That was the origin of writing. |

||

—Rin chen gter khyim, Thob. 12.6.5 | ||

Birth stories[edit]

- As Chi-med

Prior to becoming Prince Shenrab, he was born in heaven as the Bonpo master Chi-med gTsug-phud (Deathless one in a hair-knot, also named Ye-gshen gTsug-phud) to parents 'Phrul-gshen sNang-ldan and bZang-za Ring-bTsun.[47] He had later descended from Meru as the avatar Master Shenrab.[48]

In one story of Shenrab as Chi-med, his disciple was Gautama Buddha in one of Gautama's previous lives, as gSang-ba 'Dus-pa. In Shenrab's lifetime, Gautama was again his disciple, Lhabu, who had asked Shenrab what he can do to help humans. Shenrab replied to be born in sub-Himalayan India and teach them dharma. gSang-ba 'Dus-pa was born in the country Shod ma gser steng within a castle on the peak of Lang ling bang.[49] Lopon Tenzin Namdak said that the country was within sTag gzig. His parents were King Zhiwadan and Queen Lhajyindze.

- As Salwa

Prior to becoming Shenrab, he was born as Salwa in a part of heaven known as Sidpa Yesang, with an older brother Dakpa, and younger brother Shepa. His father was Sidpa Triod and mother Kunshe. They all lived in Phywa Yi Grong Khyer (City of the Phywa gods.) The three brothers were disciples of Guru Tobumtri Log Gi Che Chen. After completing their studies, they had visited Sambhogakaya Buddha Shenlha Okar, whom they asked how they can be of help to humans become liberated from samsara. Shenlha Okar advised them to incarnate (avatar) into different yugas (eras) so as to help the humans of that period gain Moksha. She had also said that the reason why she cannot do this herself is that she can only lead humans to the next stage whereas Salwa can liberate them from Samsara because he has already been purified of all obstructions. Dakpa incarnated as Tonpa Togyal Ye Khyen. After passing of his yuga, Salwa incarnated as Tonpa Shenrab for the present era. In the following era, Shepa will incarnate as Tonpa Thangma Medron.

To decide which parents Salwa should be born to, he took form as a blue cuckoo and flew atop Mount Meru (Ri-gyal lHun-po or Ri-rab) with his 2 disciples Malo and Yulo, and he contemplated. In his meditative vision, he saw that he should be born to King Gyalbon Thokar and Queen Yochi Gyalzhed Ma in their imperial palace, Barpo, Sogyed, in Olmo Lungring on the south side of Mount Yungdrung Gutsek.

Before incarnating, he built a temple atop Meru called Lha-rtse dGung-nam. The gods residing at Meru, including Brahma, Indra, and others wished he would stay. He replied, “I can’t break my promise with my tutelary deity, gShen lha ’od dkar. If you would listen to my teaching, come to see me when I’ll be born as a human child.”

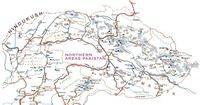

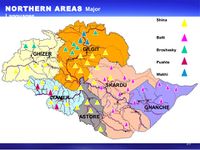

Olmo Lungring is in Karakoram[edit]

"I am inclined to suggest that the great mountains Ta la ya of sTag grig correspond to the Karakorum range." - Amnye Machen Institute[50]

Olmo Lungring is located in the Karakoram mountains of the Subcontinent, specifically Shin-majority districts of Astore and Diamer, collectively known as Shenaki (or Shinaki.) The 'gShen-yul'[51] or "land of the gShen" of Bon scriptures is where Indians speak Shin (gShen.) Another toponym in scriptures is dMu-yul, since the dMu tribe speaking the dMu language ruled the kingdom[52]. The link between the language of Olmo Lungring and Sanskrit has already been shown as it is written in Bonpo scriptures. It is also written off in Bauddh scriptures. Padmasambhava calls it Lung-Lha. Fa-hsien mentions it as Shen-Shen, where the laypeople and shramans practice Indians customs.[53]

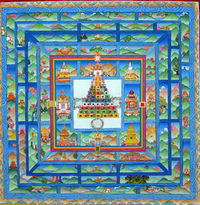

According to the gZer-mig, in the country's etymology '0l' symbolises the unborn, 'Mo' the undiminishing, 'Lung' the prophetic words of Tonpa Shenrab and 'Ring' his everlasting compassion. The kingdom is described as an 8-pedaled lotus underneath the sky, and shaped like an 8-spoked wheel.

|

'Ol-mo Lung-ring, the country of the gShen, has the aspect of Mount Meru with the four continents; [situated] on the northern side of the southern [continent of] Jambudvipa, encircling the southern part of the world, at the root of the Wish-Fulfilling Tree, facing the snow-clad Mount Ti-se, on the shores of Ma-pang g.Yu-mtsho, at the source of the Four Great Rivers, between the Fragrant Incense Mountain [sPos-ri Ngad-ldan] and the Nine Black Mountains, divided by the rivers Pag-shu and Sin-dhu: this is the place where the Teacher of the Three Times Appeared. |

||

—mDo-dus, SA.90.1[54] | ||

|

Happy country up above, Delightful, with a good atmosphere, Source of the four royal rivers, Facing Ti-se, king [of all] mountains, By the side of Ma-pham, queen [of all] lakes, 'Ol-lung Turquoise Castle, What a wonderful abode! |

||

—Srid pa spyi mdos 1,2 | ||

Its location is clearly given in Dardistan when speaking of the Indus (Sindhu) River, Tibetans write that it flows through Mar-yul (east of Lakakh[55]), 'Bru-sa on the north of Kashmir (Kachi, which borders on Zans-dkar and Purig), through sTag-gzig reaches Uddiyana (Urgyan.)[56]

The origins of the gShen nationality is explained by the scripture rTsa rGyud nYi sGron. In its story of the dMu clan's origin, the tie between modernly-recognized Mount Nanga Parbat and the text's clMu-ri sMug-po (Brown Mountain of the dMu) is seen. Mt. Nanga Parbat is a brown-colored mountain in the centre of the modern Shenaki. In the entire Indian Subcontinent it is smaller than only Mt. Meru and Mt. Everest. The story goes that the gShen came out of an egg that originated on the mountain which is said to be the Brown Mountain of the dMu.[57] After 5 generations, Shenrab is born.

Olmo Lungring is further said to have had a mountain called Mount Yungdrung (or Ri-rab Ihun-po, which is Mount Meru) from which four rivers from the four cardinal directions meet. They are: 1) Gangka/Gaiga, 2) Sidhu, 3) Pakshu/Vakshu, and 4) Siti. Today in Kashmir one can find the Kishan-Ganga, Sindhu, Cakshu, and Sita rivers. Further, it is written that Olmo Lungring had a set of 9 black mountain ranges. Today Kashmir has a range of mountains called Karakoram (which means, Black Mountains, as does its Sanskrit name Krishnagiri.) Olmo Lungring is written to be "beyond the Himalayas" and "behind the Sharp Teeth (dBal-so) Glacier." This matches the description of Kashmir, which has the Karakoram range that is both beyond the Himalayas and west of the Siachen Glacier. Dan Martin is of the viewpoint that Olmo Lungring consisted of Baltistan, Gilgistan, northern Jammu & Kashmir state, present-day Pakistan (i.e., Swat, Chitral, etc.) and perhaps Badakshan, along with the mountainous parts of Uttar Pradesh.[58] As Lord Shenrab was of the dMu-gShen Dynasty, it is probable that he was of Shin ethnicity, which resides mainly in the Karakoram, because 'dMu' refers to sky-gods while 'gShen' is a demonym. 'gShen' is just a variant of 'Shin' as both are used to denote the same ethnicity[59] in modern times, but Shin has taken precedence. (And another toponym of gShen-yul is dMu-yul.)

Tracing the diffusion of Yungdrung Bon leads us to Shenaki as its epicentre because the theory of Guru Shenrab having been a Shin is further supported by the fact that Bon teachings were delivered to Bon masters in Shenaki's adjacent territories of Gilgit (to Shenpo Ge Tene Logya), the rest of Kashmir (to Shenpo Braba Meruchan), and another part of India (to Shenpo Lisha.) Furthermore, in order to convert people within different nations, Guru Shenrab incarnated into different forms; "Arya Jambala" for sTag-gzig, gShen-lha Od-dkar for Zhang Zhung, Confucius for China, Sage Atreya for sub-Karakoram Kashmir, and Hayagriva for Uddiyana (Swat Valley or Urgyan.)[60] He would not have been written to have incarnated as a Hindu figure with a Sanskrit title if sTag-gzig's natives were Iranians (whose pantheon did not include Kuber.) He did after all incarnate as locally familiar forms of Tibetan gShen-lha and Chinese Confucius.

"Among the four continents, Jambudvipa is the best one. At the world's navel, there is the Indian city of Vajrasana. From there, after crossing the Nine Black Mountains, there is Mt. Ti-se, the king of glaciers. At its west side the river Sindhu flows down."

The bsGrags byang[61] says, "Mountain ranges (gangs-kyis [kyi] ra-ba-can in the centre; to the west are sTag-sde and gZig-phan." It also goes on to say, "The border between sTag-gzig in the west and the mountain ranges in the centre is demarcated by [Mount] Ba-dag-sha dung-gi mgo-mo...[62] The border between Ge-sar [in the north] and sTag-gzig is demarcated by [Mount] Nyi-gong snyan-dmar...[63] The border between sTag-gzig and rGya-gar [in the south] is demarcated by [Lake] Mon-mtsho nag-po ting-ring...[64] The border between sTag-gzig and Tibet is demarcated by [Mount] rDo-dgod brag-ring[65]."[66] In these passages, one can see that sTag-gzig is a massive empire bordering different regions, and because it borders the Sub-Himalayan portion of India, that means Kha-che (Kashmir) is a part of the empire.

The mDo 'dus[67] states that Mount Ti-se is the centre[68] of the earth, and to its west is the country dMu-yul. This alone is clear as mud that dMu-yul (a part of sTag-gzig) is the Karakoram region.

Confusion of terminology[edit]

"Each nationality of Jambu Island has its own name for it, among them: The people of Zhang-zhung call it Staggzig Khrom-pa'i Gling. The Indian people call it northern Shambhala, the supreme place. Tibetans call it the land of Stag-gzig, 'Ol-mo-lung -ring.'" - Shar-rdza Bkra-shis-rgyal-mtshan[70]

Some scholars have confused sTag-gzig as being an Iranian land. However, this is a latter-added term while Olmo Lungring is the earliest occurring name of Bonpa Shenrab's country. Dan Martin writes that the phrase became more common in the 12th century. Even in Authenticity of Open Awareness it is explained that Bon spread to Olmo Lungring first, and then to sTag-gzig, therefore showing that Olmo a different country than sTag-gzig. According to Lopon Tenzin Namdak, this country ("Tazik" or sTag-gzig) was said to be located northwest of Tibet. The Sino-Tibetan Treaty of 821-822 CE identifies 4 countries bordering on the Tibetan Empire; rGyagar (Sub-Himalayan India), Tashig (Abassid Empire), and Drugu Nomel (Turkistan), and rGyanag (China.)[71] Here 'Tashig' is a variant of 'sTag-gzig'.

"This negative influence was also felt by the Bonpos, so that the new Bonpos of later times ended by placing 'Ol-mo Lung-ring in sTag-gzig, creating the expression "sTag-gzig Ol-mo-lung." There is no other logical motivation for that attribution." - Chogyal Namkhai Norbu[72]

Definition of 'Tajik'[edit]

The term Tazik appears almost identical to 'Tajik'. The reason why some latter Bon writers began using the term to phrase Olmo Lungring's name is because they wanted the-then generations of their era's to understand in modern terms. Then, from 7th century onward, parts of the Indian Subcontinent including Kashmir was under Arab rule and 'Tajik' is synonymous with 'Arab'. Hence, sTag-gzig was the was politically correct word Arab-occupied Olmo Lungring. Even M.G. Chitkara writes, "The Bon religion originated in the land of Olmo Lungring, a part of a larger country called Tazig."[73] An Arabic attributed to the time of Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun (813-833 CE) inscription reads of the Arab victory over the rulers of both the Wakhan and Bolor (Gilgit.)[74] Michael Walter too criticizes the idea of sTag-szig being in the Iranian Plateau, and proposes instead that the Tibetans are just referred to the Abbasid Empire. The Abbasid and Umayyid empires were mainly Arab-governed dynasties. Arab influence would continue even after the regions were ruled by post-Arab dynasties because Arabic was an official language even under Tahirids (821–873 CE), Saffarids (861–1003 CE), and Samanids (819–999 CE.) Anna Akasoy writes that by referring to Olmu Lungring as sTag-gzig, the Tibetans could be intending the parts of the Abbasid Empire closer to them.[75] There is also Tazipora village in Kashmir, and historically the Persians used the term 'Tazi' (with the same meaning as 'Tazik') to also connate anything related to Arabs[76]. The term was used in India to refer to Arabs. Nilakantha Daivagna had compiled the Tajika Jyotisa in Arabic. There is also a coin minted in Lahore that was issued under Sultan Ghazni's reign which reads, "Tajikiya Samvat 419" (Arabic Era 419.)[77] Even the Chinese word for 'Arab' comes from 'Tazik' as a Chinese source reads that in 758 CE both Persians ("Po-se") and Arabs ("Ta-shih", which comes from 'Tazik') had burnt and sacked Canton.[78]

Connection to Himalayan areas[edit]

Some scholars have included Kashmir within the historical region of Olmo Lungring. Today in Kashmir one can find place names reminiscent of Shambhala, such as Sangrin and Sangam. Kashmir like Uttarakhand, also being westwards of Mount Kailash fits the description of being a part of Shambhala. Further, the Shambhala that Bon scriptures refer to is also likely to be in Kashmir, as Samba and Sumbal Bag are towns within Kashmir. With the popularity of Buddhism rising in India, preachers such as Padmasambhava began moving to Tibet to preach the religion. Over the next few centuries, Buddhism with its missionaries from India often settled in Tibet and along with Tibetan Buddhist lamas preached Buddhism. However, Olmo Lungring was a part of the greater Shambhala region. According to the gZi-brjid, Dimpling is the same as Shambhala.

Kenbo Nyima Wangyal believes that Shambhala had extended from Gilgit in its west to Namtso in its east.[79] The capital of Shambhala was Khyunglung Ngulkhar, "The Silver Palace of the Garuda Valley", with its ruins found in the upper Sutlej Valley southwest of Mount Kailash, which is modern-day State of Uttarakhand. Sambhal is the name a village in present-day Mordabad district of Uttarakhand, which has been known to have been centuries ago a centre of Tantra.[80] Sambal is a Sanskrit name meaning, "the place of peace, of tranquillity.")

Authors such as Toni Huber write of how Tibetans have maintained a ritual relationship to India, and consider India as their holy land.

A teacher for the world[edit]

According to scriptures, Shenrab, like ascetic Rishabha, traveled other kingdoms outside of India.

"Among the countries to the north and south of Jambu Island, the places where the teacher pressed down with His feet on the earth, with His actual body are the following: China, Tanguts, India, Nepal, O-rgyan, Za-hor, Kashmir, Turkharistan, Khotan, Ta-zig, Zhang Zhung, Mon-yul, Khotan, Phrom, Gesar, Bru-sa, Qarluq, Uighur, and Tibet." - dBra-ston[81]

This list of countries is based on the list of Tibetan placenames of countries from the scripture Srid-pa Las-kyi gTing-zlog-gi rTsa-rgyud Kun-gsal Nyi-zer Sgron-ma. It substituted "India" for "rGya-gar", which is actually, more accurately "sub-Himalayan India". O-rgyan is Oddiyana. Bru-sa is Gilgistan. Tunguts refers to the land in the Kurban-Tungut Desert in southern Kazakhstan. Ge-sar is the part of mainland China north of Tibet yet west Tarim Basin.

"The blessed, spread the teachings and converted beings within the [Eighteen] Great Countries of the Gods (Lha) Ta-zig (sTag-gzig), Oddiyana (U-rgyan), Tokharistan (Tho-gar), Camara (rNga-yab), rNga-yab-zhan (?), Za-hor, Turkestan (Gru-gu), Little Balur (Bru-sha), Kashmir (Kha-che), Khotan (Li), Nepal (Bal), India, China, Nan-chao ('Jang), Hor Gesar, snowy Tibet and Zhang-zhung. Ultimately, they all visibly entered Bon Proper (Bon nyid.)" - Dkar-ru Grub-dbang[82], 19th century Bon-po scholar

The gSang-sngags Rdzong-'phrang Nyi-'od rGyan by Thu'u-kbwan was a book of notes from a summit between Bonpas of countries of Olmo Lungring, sub-Himalayan India, Tibet, China, Turkharistan, and some others. The summit's would always take place in a cave named Mang-mkhar lCang-phrang. Cave temples or cave monasteries were very popular throughout Hindu history. (Even today pilgrimages continue to them.)

Dbra-stpm of the early 20th century cites the Nyi-sgron for a list of country that Shenrab travelled to.

| Among the countries to the north and south of the Jambu Island, the countries where the Teacher pressed down the earth with His feet, with His actual body, are the following: China, Tanguts, India, Nepal, O-rgyan, Za-hor, Kashmir, Turkharistan, Khotan, Ta-zig, Zhang-zhung, Mon-yul, Khotan, Phrom Ge-sar, Bru-sha, Qarluq, Uighur, and Tibet. He went to these countries, and there remain even now visible signs of His presence, footprints and the like, so it is right that all should believe. | ||

—Nyi-sgron | ||

Rgyal-rabs Bon-gyi 'Byung-gnas lists rGya-gar (India), rGya-nag (China), Me-nyang (Tanguts), Balpo (Nepal), O-rgyan (Oddiyana), Za-hor, Kha-che (Kashmir), Thod-dkar (Tokharia), Li-yul (Khotan), sTag-szig (Karakoram), Zhang-zhung, Bod (Tibet), Mon (Bhutani), Khyi-than (Khitans), Khrom, Ge-sar, Bru-sha (Gilgit), Gar-log (Qarlugs), Yu-gur (Uighurs)

Srid-pa Rgyud-kyi Kha-byang Chen-mo states that Shenrab had incarnated in different times and places.

| The Blessed spread the teachings and converted beings within the [Eighteen] Great Countries of Gods (lha), Tazig, Oddiyana, Tokharistan, Camara, Rnga-yab-zhan, Zahor, Turkestan, Little Balur, Kashmir, Khotan, Nepal, India, China, Nan-chao, Gor Gesar, snowy Tibet, and Zhang-zhung. | ||

—Srid-pa Rgyud-kyi Kha-byang Chen-mo | ||

Depictions[edit]

Normally the Guru is represented as yellow in artworks, and he is noted to be of "golden" color, or like that of a "jewel." However, depictions of him exist in the form of painted canvases[83] and cave paintings wherein he is shown as blue[84] or black.

Incarnations[edit]

Apart from the avatars of Chi-med and Salwa, Tonpa Shenrab is believed to have incarnated as Tonpa Tritsug Gyalwa[85]. Shenrab manisfested himself as Nampar Gyalwa (Fully Victorious One) and 4 wrathful gods to subdue demons that sought to destroy a monestary that was built according to his guideline.[86]

While in Zhang Zhung on Mount Kailash he tried subjugating violent spirits there. He had begun reciting the Tendrin Mantra and then eminated as Hayagriva, appearing of a red body and green head, dressed in golden ornaments and carrying a flaming red sword.[87] Other martial spirits began to appear and overwhelmed the violent spirits present.

|

The body emanation of the victorious one, Shenrab, manifested in the form of "Great Fierce Secret Conqueror of Demons.” He revealed this destroyer manifestation with sharp arrows, magic bombs, magic missiles, and spells to the assembly of deities of the upper and lower worlds. All at once, the magical manifestations of each of the deities were neutralized. The deities then vowed not to transgress the commands of Shenrab and not to renounce their oath. |

||

—Bon scripture | ||

- In China

DTo-mba Shi-lo-mi-wu[88] is another avatar of Shenrab. He is worshipped by the Na-khis in southwestern China in the provinces of Yunnan its NW part) and Sichuan (its SW part.) He is always portrayed as green-bodied, apart from one image that exists in a manuscript wherein he is shown as golden.

"Like Shenrab Mibo, Dongba Shiluo resided in heaven from where he descended to earth to suppress the multitude of demons that caused havoc among humanity."[89]

- In Sikkim

In Sikkim, folk legends recognize Bon Tenpa Yab Yum as Tonpa Shenrab, seated on an altar of lineage protectors in the heavenly paradise of Bon gods.[90]

- In Nepal

In Nepal, the kul-jhakris (family-priests) of the Tamang tribe chant from the Bumba Shyareb and dedicate themselves to Guru Shyareb[91], who is none other than Shenrab.

Related Articles[edit]

- Yungdrung Bon

- The spread of Hinduism

- Brahm

- Avatar

- Zarathustra was born in Kashmir

- Yama's Kingdom is in Kashmir

- Ravana's Lanka is in Kashmir

- Hanuman's Kishkindha is in Kashmir

- History of ancient geography

External Resources[edit]

- "Shenrab’s Ancestors And Family Members: Where Do They Come From?"

By Kalsang Norbu Gurung

References[edit]

- ↑ P. 221 Bon, the magic word: the indiginous religion of Tibet By Samten G. Karrmay, Jeff Watt

- ↑ P. 3 Bø and Bön: Ancient Shamanic Traditions of Siberia and Tibet in Their Relation to the Teachings of a Central Asian Buddha By Dmitry Ermakov

- ↑ It means Shen Palace.

- ↑ It is in western Tibet.

- ↑ The bsTan rTsis

- ↑ P. 339 The Golden Letters: The Three Statements of Garab Dorje, First Dzogchen Master By John Myrdhin Reynolds

- ↑ P. 281 Feast of the morning light: the eighteenth century wood-engravings of Shenrab's life-stories and the Bon Canon from Gyalrong By Samten Gyaltsen Karmay

- ↑ P. 117 Traces in the Desert: Journeys of Discovery Across Central Asia By Christoph Baumer

- ↑ P. 206 Bø and Bön: Ancient Shamanic Traditions of Siberia and Tibet in Their Relation to the Teachings of a Central Asian Buddha Dmitry Ermakov

- ↑ It means Traytrimsha Devas.

- ↑ Sa-tshigs-kyi yul dbus

- ↑ It means Gautama Buddha in prior life.

- ↑ P. 46 Chod Practice in the Bon Tradition By Alejandro Chaoul

- ↑ dMu-gShen; P. 4 Bonpo Dzogchen Teachings By Tenzin Namdak

- ↑ P. 3 Twelve Deeds: A Brief Life Story of Tonpa Shenrab, the Founder of the Bon Religion By Sangye Tenzin (Menri Lopon)

- ↑ P. 49 The Tibet Journal Volume 24 By Library of Tibetan Works & Archives

mDzod sgra 'grel (p.10, 19): “In the language of Zhang zhung, mu ling (li) ne ting slas spring ling. In Tibetan, mkha 'rlung me chu sa dang gling, ‘which means sky, wind, fire, water, earth and continent.’”

rGyud ting mur g.yu rtse (fol.5r4): “In the language of Zhang zhung mu ag par smar la e ma ho. In Tibetan, mu med nam mkha 'dag pa'i ngog / gsang dang bzang po ngo mtshar che ba'i gzhal yas na, ‘which means the surface of the endless and clear sky, secret, good and wonderful divine residence.’”

Me ri gsang ba'i 'khor lo (fol.lv2): “In the language of Zhang zhung, A ti mu wer. In Tibetan, skye 'gag med pa nam mkha'i rgyal po, ‘which means the king of the sky with neither birth nor interruption.’”

The rNam bshad gsal sgron (P.52, 8) states that ‘Mu’ means sky. - ↑ P. 45 The Tibet Journal, Volume 24 By Library of Tibetan Works & Archives

- ↑ P. 86 A History of Zhang Zhung and Tibet, Volume One: The Early Period By Chogyal Namkhai Norbu

- ↑ Lungta, Issue 16 By Amnye Machen Institute

- ↑ In Tusita heaven he is known by the name; P. 519 Tibetan-English dictionary By Sarat Chandra Das

- ↑ He is known as the son of heaven and as Tog-dkar-po.

- ↑ "Mi rGyud lha las grol ba"

- ↑ P. 152 Rolf Stein's Tibetica Antiqua: With Additional Materials By R. Rolf Alfred Stein

- ↑ The Heart of the Buddha: Entering the Tibetan Buddhist Path By Chögyam Trungpa

- ↑ P. 4 Bonpo Dzogchen Teachings By Tenzin Namdak

- ↑ It means modern Shin.

- ↑ P. xix The Treasury of Good Sayings A Tibetan History of Bon By Bkra-śis-rgyal-mtshan (Śar-rdza); translated and edited by Samten G. Karmay

- ↑ It means four buildings and four mchod-rten.

- ↑ P. 95 The Cultural Monuments of Tibet's Outer Provinces: Kham By Andreas Gruschke

- ↑ P. 273 Sacred Spaces and Powerful Places in Tibetan Culture: A Collection of Essays Toni Huber

- ↑ P. 56 Bon, the magic word: the indiginous religion of Tibet By Samten G. Karrmay, Jeff Watt

- ↑ P. 13 The Twelve Deeds: A Brief Life Story of Tonpa Shenrab, the Founder of the Bon Religion By Sangye Tenzin (Menri Lopon)

- ↑ P. 276 The World's Religions: The Religions of Asia edited by Friedhelm Hardy

- ↑ Pe. I6.I9; P. 86 A History of Zhang Zhung and Tibet, Volume One The Early Period · Volume 1 By Chogyal Namkhai Norbu ·

- ↑ Brother of the rest of the dpag pa'i mi bzhi (Drum shing bcud 'thung, g.Yung drung khyim bdun, and Me tog sbub gnas.)

- ↑ Brother of rJe rigs su btsun pa, Bram ze rigs su gtsang ba and rMang rigs su rdol pa.

- ↑ Nyi zer sgron ma; P. 51 The Tibet Journal: Volume 24 By Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, [Dharamsala, India]

- ↑ Thob. 12.6.5

- ↑ P. 150 A History of Zhang Zhung and Tibet, Volume One: The Early Period By Chogyal Namkhai Norbu

- ↑ “But there are also 360 divinatory spirits (bdud lha) known to the Bön. That number recurs frequently, Bönpo claim their doctrines were originally written in 360 languages, a number of other.”;

P. 369-370 Kailas Histories: Renunciate Traditions and the Construction of Himalayan Sacred Geography By Alex McKay - ↑ P. 138 Bø and Bön: Ancient Shamanic Traditions of Siberia and Tibet in Their Relation to the Teachings of a Central Asian Buddha By Dmitry Ermakov

- ↑ "In 'Dzam-bu-gling there are one thousand different languages, and the Bon reached the ears of three hundred and sixty of these.";

P.17 The Treasury of Good Sayings: A Tibetan History of Bon By Bkra-śis-rgyal-mtshan (Śar-rdza) - ↑ Even Asvaghosa in his Buddha-karita, Book 5 75-87 mentions it. This is not to be conflated with the Kapita ('Kie-pi-tha'/'Kah-pi-t'a' or modern Sankisa Basantpur), A.K.A. Sankasya, of western Uttar Pradesh for which is written at Samkasya, or Kapitha, "there were four Buddhist monasteries with above 1,000 Brethren, all of the Sammatiya School" (p. 333). That one in U.P. state is also known as Devavatara. It is also not to be conflated with Ka-pi-lo-su-to (Kapilavastu or Lumbini), or with the Kapatesvara tirth[1] in Kother, Kashmir.

- ↑ P. 33 Chod Practice in the Bon Tradition By Alejandro Chaoul

- ↑ P. 33 The Tibet Journal, Volume 7 By Library of Tibetan Works & Archives

- ↑ P. 33 The Tibet Journal, Volume 7 By Library of Tibetan Works & Archives

- ↑ P. xxi The Treasury of Good Sayings: A Tibetan History of Bon edited by Samten G. Karmey

- ↑ P. 44 The Great Perfection (rdzogs chen): A Philosophical and Meditative Teaching By Samten Karmay

- ↑ P. 428 The Oral Tradition from Zhang-Zhung: An Introduction to the Bonpo Dzogchen Teachings of the Oral Tradition from Zhang-zhung Known as the Zhang Zhung Snyan Rgyud By John Myrdhin Reynolds

- ↑ Lungta, Issue 16 By Amnye Machen Institute

- ↑ Gshen-yul Ol-mo-gling; P. 263 Sacred Spaces and Powerful Places in Tibetan Culture: A Collection of Essays By Toni Huber

- ↑ P. 688 Tibetan Studies: Part 2 By International Association for Tibetan Studies. Seminar, Helmut Krasser

- ↑ Chapter II A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms Being an Account by the Chinese Monk Fa-hsien of Travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414) in Search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline By Faxian

- ↑ P. 112 A History of Zhang Zhung and Tibet, Volume One: The Early Period By Chogyal Namkhai Norbu

- ↑ P. 417 Historical Dictionary of Tibet By John Powers, David Templeman

- ↑ P. 396 Opera Minora, Part 2 Giuseppe Tucci

- ↑ In the myth, the man from the egg was Mes-po dMu-phyug sKyer-zhon. He married lHa-mo Gang-drag-ma and their son was dMu-btsan bZher-gyi rGyal-po, who married Phya-lcam rGyal-mo to give birth to their son dMu-btsan rGyal-ba, who married Ring-nam rGyal-mo to give birth to their son dMu-rgyal Len-gyi Them-skas, who married lHa-za 'Phrul-mo to give birth to their son rGyal-po Thod-dkar.; P. 85 A History of Zhang Zhung and Tibet, Volume One: The Early Period By Chogyal Namkhai Norbu

- ↑ P. 166 Tantric Revisionings: New Understandings of Tibetan Buddhism and Indian Religion By Geoffrey Samuel

- ↑ P. 4 Hunza, an ethnographic outline By H. Sidky

- ↑ P. 47 Civilization at the foot of Mount Sham-po: the royal house of lHa Bug-pa-can and the history of g.Ya'-bzang : historical texts from the monastery of g.Ya'-bzang in Yar-stod, central Tibet Tsering Gyalbo, Guntram Hazod, Per K. Sørensen

- ↑ f.4r.4

- ↑ f.5v.5

- ↑ f.6r.2

- ↑ f.6r.3

- ↑ f.6r.5

- ↑ P. 688 Tibetan Studies: Volume 256, Part 2 By International Association for Tibetan Studies. Seminar, Helmut Krasser

- ↑ mDo 'dus p.15.5

- ↑ Tibetan: sa tshigs kyi dbus

- ↑ P.xx The Tibetans By Matthew Kapstein, Blackwell, 2006.

- ↑ P. 282 Sacred Spaces and Powerful Places in Tibetan Culture: A Collection of Essays By Toni Huber

- ↑ P. 48 The Holy Land Reborn: Pilgrimage and the Tibetan Reinvention of Buddhist India By Toni Huber

- ↑ P. 112-113 A History of Zhang Zhung and Tibet, Volume One: The Early Period By Chogyal Namkhai Norbu

- ↑ P. 120 Buddha: Maths and Legends v. 10: A World Faith: Maths and Legends By M.G. Chitkara

- ↑ P. 216 History of civilizations of Central Asia Vol. 4 The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Pt. 1 The historical,social and economic setting By M S Asimov

- ↑ Islam and Tibet – Interactions along the Musk Routes By Anna Akasoy

- ↑ P. 109 The Races of Afghanistan: Being a Brief Account of the Principal Nations Inhabiting that Country By Henry Walter Bellew

- ↑ P. 309 Indian Epigraphy By D. C. Sircar

- ↑ P. 643 Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas Volume I edited by Stephen A. Wurm, Peter Mühlhäusler, Darrell T. Tryon

- ↑ P. 315 Unbounded Wholeness: Dzogchen, Bon, and the Logic of the Nonconceptual By Anne Carolyn Klein, Geshe Tenzin Wangyal By Rinpoche

- ↑ P. 31 Bulletin of Tibetology, Issues 1-3 By Namgyal Institute of Tibetology,

- ↑ P. 35 Unearthing Bon Treasures: Life and Contested Legacy of a Tibetan Scripture By Dan Martin

- ↑ P. 10 Mandala Cosmogony: Human Body Good Thought and the Revelation of the Secret Mother Tantras of Bon By Dan Martin

- ↑ The Search For Shangri-La: A Journey into Tibetan History By Charles Allen

- ↑ P. X Path of the Swan: The Maitreya Chronicles, Part 1 By Charu Singh

- ↑ P. 6 The Four Wheels of Bön By Yongdzin Lopon Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche, Dmitry Ermakov, Carol Ermakova

- ↑ P. 172 Tibetan Painting: The Jucker Collection By Hugo Kreijger

- ↑ P. 191 Tibetan Ritual By Jose Ignacio Cabezon

- ↑ P. 505 Serie orientale Roma, Volume 4, Issue 1 By Joseph Francis Charles Rock

- ↑ P. 96 Sons of Heaven, Brothers of Nature: The Naxi of Southwest China By Pedro Ceinos Arcones

- ↑ P. 384 Lamas, Shamans and Ancestors: Village Religion in Sikkim By Anna Balikc

- ↑ P. 161 Journal of the Indian Anthropological Society, Volume 13 By The Society