Who is a Hindu?

By Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami and Himanshu Bhatt

Hinduism is a diverse tradition and very different from other monolithic religions. In the monolithic sense, it is defined by The Four Pillars. Faith (sraddha) is individualistic whereas religion (dharma) is collective, and so Hindus are encouraged to explore their faith, which is why there are more Hindu scriptures and textual opinions on spirituality than of any other religion. There isn’t a single scriptural or spiritual authority to define matters of the faith for Hindus, unlike in some other religions with a central pontiff. There are several different denominations, the four largest being Vaishnava, Saiva, Shakta and Smartha. Further, there are numberless schools of thought, or sampradayas, expressed in tens of thousands of guru lineages, or paramparas. Each is typically independent and self-contained in its authority. In a very real sense, this grand tradition can be defined and understood as ten thousand faiths gathered in harmony under a single umbrella called Hinduism, Sanatan Dharma. The tendency to overlook this diversity is the common first step to a faulty perception of this religion. Most spiritual traditions are simpler, more unified and unambiguous. In the definitive sense a Hindu or Sanatan is any person who believes that abiding by the Law of Karma and Five Precepts, and practicing Karma, Bhakti, or Gyana yogas the soul can attain Moksha or spiritual progress. And a Hindu is one of the members of the Ārya Samudāy.

All too often, despite its antiquity, its profound systems of thought, the beauty of its art and architecture and the grace of its people, Hinduism remains a mystery. Twisted stereotypes abound that would relegate this richly complex, sophisticated and spiritually rewarding tradition to little more than crude caricatures of snake-charmers, cow-worshipers and yogis lying on beds of nails.

Fortunately, there is an easier, more natural way to approach the vastness of Hinduism. From the countless living gurus, teachers and pundits who offer clear guidance, most seekers choose a preceptor, study his teachings, embrace the sampradaya he propounds and adopt the precepts and disciplines of his tradition. That is how the faith is followed in actual practice. Holy men and women, counted in the hundreds of thousands, are the ministers, the defenders of the faith and the inspirers of the faithful.

Four Basic Principles[edit]

"At this supremely dangerous moment in human history, the only way of salvation is the ancient Hindu way." - Mark Twain

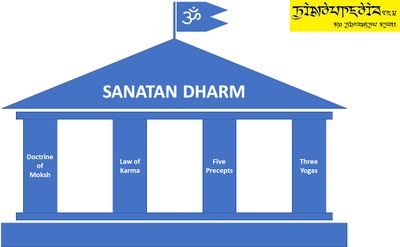

One way to gain a simple (though admittedly simplistic) overview is to understand the four essential beliefs shared by the vast majority of Hindus:

- Doctrine of Moksha (salvation),

- Law of Karma (what salvation is based on),

- Five Precepts (how to stay in accord with the law), and

- Three Yogas (support of the precepts.)

It could be said that living by these four principles (tattvas) or pillars is what makes a person a Hindu.

- Reincarnation: Reincarnation, punarjanma, is the natural process of birth, death and rebirth. At death we drop off the physical body and continue evolving in the inner worlds in our subtle bodies, until we again enter into birth. Through the ages, reincarnation has been the great consoling element within Hinduism, eliminating the fear of death. We are not the body in which we live but the immortal soul which inhabits many bodies in its evolutionary journey through samsara. After death, we continue to exist in unseen worlds, enjoying or suffering the harvest of earthly deeds until it comes time for yet another physical birth. The actions set in motion in previous lives form the tendencies and conditions of the present life and the next. Reincarnation ceases when karma is resolved, God is realized and moksha, liberation, is attained. The Vedas state, “After death, the soul goes to the next world, bearing in mind the subtle impressions of its deeds, and after reaping their harvest returns again to this world of action. Thus, he who has desires continues subject to rebirth”[1].

- All-Pervasive Divinity: As a family of faiths, Hinduism upholds a wide array of perspectives on the Divine, yet all worship the one, all-pervasive Supreme Being hailed in the Upanishads. As Absolute Reality, God is unmanifest, unchanging and transcendent, the Self God, timeless, formless and spaceless. As Pure Consciousness, God is the manifest primal substance, pure love and light flowing through all form, existing everywhere in time and space as infinite intelligence and power. As Primal Soul, God is our personal Lord, the source of all three worlds, our Father-Mother God who protects, nurtures and guides us. We beseech God’s grace in our lives while also knowing that He/She is the essence of our soul, the life of our life. Each denomination also venerates its own pantheon of Divinities, Mahadevas, or “great angels,” known as Gods, who were created by the Supreme Lord and who serve and adore Him. The Vedas proclaim, “He is the God of forms infinite in whose glory all things are—smaller than the smallest atom, and yet the Creator of all, ever living in the mystery of His creation. In the vision of this God of love there is everlasting peace. He is the Lord of all who, hidden in the heart of things, watches over the world of time” [2].

- Karma

- Karma literally means “deed” or “act” and more broadly names the universal principle of cause and effect, action and reaction which governs all life. Karma is a natural law of the mind, just as gravity is a law of matter. Karma is not fate, for man acts with free will, creating his own destiny. The Vedas tell us, if we sow goodness, we will reap goodness; if we sow evil, we will reap evil. Karma refers to the totality of our actions and their concomitant reactions in this and previous lives, all of which determines our future. It is the interplay between our experience and how we respond to it that makes karma devastating or helpfully invigorating. The conquest of karma lies in intelligent action and dispassionate reaction. Not all karmas rebound immediately. Some accumulate and return unexpectedly in this or other births. The Vedas explain, “According as one acts, so does he become. One becomes virtuous by virtuous action, bad by bad action”[3].

- Five Precepts

- Three Yogas

- Other principles

- Dharma

- When God created the universe, He endowed it with order, with the laws to govern creation. Dharma is God’s divine law prevailing on every level of existence, from the sustaining cosmic order to religious and moral laws which bind us in harmony with that order. In relation to the soul, dharma is the mode of conduct most conducive to spiritual advancement, the right and righteous path. It is piety and ethical practice, duty and obligation. When we follow dharma, we are in conformity with the Truth that inheres and instructs the universe, and we naturally abide in closeness to God. Adharma is opposition to divine law. Dharma is to the individual what its normal development is to a seed—the orderly fulfillment of an inherent nature and destiny. The Tirukural reminds us, “Dharma yields Heaven’s honor and Earth’s wealth. What is there then that is more fruitful for a man? There is nothing more rewarding than dharma, nor anything more ruinous than its neglect.” [4]

| Dharma is the foundation of the whole universe. In this world people go unto a person who is best versed in dharma for guidance. By means of dharma one drivers away evil. Upon dharma everything is founded. Therefore, dharma is called the highest good. | ||

—Taittiriya Aranyaka | ||

- Rta

| Rta is the universal norm identified with truth which, when brought to the level of humanity, became known as dharma, the righteous order here on Earth. | ||

—Taittiriya Aranyaka | ||

Put simply rta is the [divine] order, dharma is the duty, and karma is our actual behaviour.

Worldview From Four Principles[edit]

- See also: Darshana and Basis For Specific Darshans

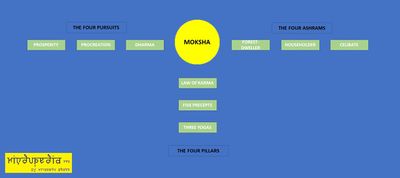

A Hindu is anyone who believes that by practicing the Five Precepts and Three Yogas, the soul will be in conformity with the Law of Karma to achieve Moksha.

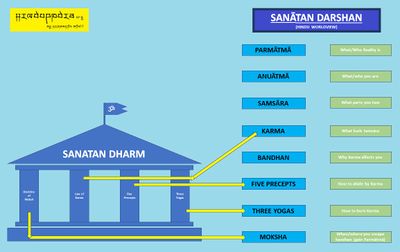

The darshanas are an expansion of the general Hindu worldview, which is based on the four pillars of Hinduism.

A research paradigm in philosophy consists usually of 4 fields; ontology, epistemology, axiology, and methodology. It is used for the study or the world and its knowledge. Hinduism itself is a research paradigm because of the 4 pillars it is based on and what those pillars represent. The ontology (or research paradigm) of Hinduism can be summarized on 8 principles which answer the 6 W's (who-what-where-why-when-how.) The purpose of darshanas, which expands this general worldview, is to investigate reality deeper, making them each specific worldviews.

The Hindu research paradigm:

| Pillar | Meaning | In terms of a philosophy | In terms of doctrine | In terms of theory | In terms of an experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctrine of Moksh | Salvation | Ontology (nature of reality) |

Ideal | Theoretical knowledge | Goal |

| Law of Karma | What salvation is based on | Epistemology (how to examine reality) |

Ideal | Theoretical knowledge | Confounding factor |

| Five Precepts | How to stay in accord with that law | Axiology (ethics of reality) |

Application | Theoretical instruction | Objective |

| Three Yogas | How to support the Precepts for burning karma | Methodology (how to discover knowledge/Self-knowledge) |

Application | Theoretical instruction | Objective |

The general overview:

- Parmātmā (or Brahm) - What is Reality

- Anuātmā - What are you

- Samsāra - What parts you two

- Karma - What fuels Samsāra

- Bandhan (usually seen as Māyā) - Why Karma affects you; because you are constantly interacting [producing karmas] with the matter of this reality

- Five Precepts - How to abide by Karma while suspended in Bandhan

- Three Yogas - How to burn Karma and escape Bandhan

- Moksha - When you escape Bandhan and attain Reality

Struggle To Improve The Soul[edit]

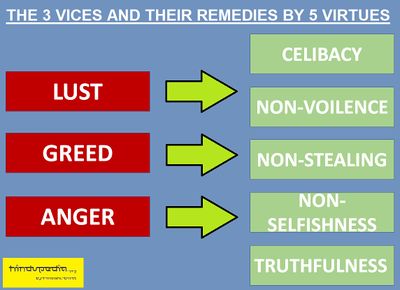

The Bhagavad Gita declares that there are "three gates to hell" - lust, greed, and anger.[5]

| Threefold is this way, to hell,--ruinous to the self,--lust, anger, and likewise avarice; therefore one should abandon this triad. Released from these three ways to darkness, O son of Kuntî! a man works out his own welfare, and then proceeds to the highest goal. | ||

—Bhagavad Gita 16.5[6] | ||

- Five Precepts

- Brahmacharya (Celibacy) - i.e., sex only with a marriage partner

- Ahimsa (Non-violence) - i.e., not causing harm to sentient living beings, humans and animals

- Asteya (Non-stealing) - i.e., not taking anything without consent

- Aparigraha (Non-selfishness) - i.e., sharing

- Satya (Truthfulness) - i.e., not speaking untruths

Reconciling Materialism with Spiritualism[edit]

- See also: Puruṣārtha

“Hinduism at its best has spoken the only relevant truth about the way to self-realization in the full sense of the word.” – Count Hermann Keyserling

Although all creatures have desires (and are materialistic by nature), it is important that we act logically and not carelessly. All humans make mistakes but the Five Precepts laid down guide a human to avoid major missteps in life (and if those missteps have occurred, how to prevent their recurrence.)

Applying those while pursing the four goals of life is required. These four pursuits are:

Living life with spiritual responsibility helps us avoid hedonism (which leads to rebirths as humans and animals.) The hedonistic worldview is purely materialistic as follows and 'heaven' and 'salvation' are used only metaphorically by it:

| “The enjoyment of heaven lies in eating delicious food, keeping company of young women, using fine clothes, perfumes, garlands, sandal paste... while moksha is death which is cessation of life-breath... the wise therefore ought not to take pains on account of moksha.

A fool wears himself out by penances and fasts. Chastity and other such ordinances are laid down by clever weaklings.” |

||

—Sarvasiddhanta Samgraha, Verses 9-12 | ||

Hinduism’s Unique Value Today[edit]

There are good reasons for Hindus and non-Hindus alike to study and understand the nature of Hinduism. The vast geographical and cultural expanses that separate continents, peoples and religions are becoming increasingly bridged as our world grows closer together. Revolutions in communications, the Internet, business, travel and global migration are making formerly distant peoples neighbors, sometimes reluctantly.

It is crucial, if we are to get along in an increasingly pluralistic world, that Earth’s peoples learn about and appreciate the religions, cultures, viewpoints and concerns of their planetary neighbors. The Sanatana Dharma, with its sublime tolerance and belief in the all-pervasiveness of Divinity, has much to contribute in this regard. Nowhere on Earth have religions lived and thrived in such close and harmonious proximity as in India. For thousands of years India has been a home to followers of virtually every major world religion, the exemplar of tolerance toward all paths. It has offered a refuge to Jews, Zoroastrians, Sufis, Buddhists, Christians and nonbelievers. Today over one hundred million Indians are Muslim, for the most part magnanimously accepted by their majority Hindu neighbors. Such religious amity has occurred out of an abiding respect for all genuine religious pursuits. The oft-quoted axiom that conveys this attitude is “Ekam sat anekah panthah,” “Truth is one, paths are many.” What can be learned from the Hindu land that has given birth to Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism and has been a generous protector of all other religions? India’s original faith offers a rare look at a peaceful, rational and practical path for making sense of our world, for gaining personal spiritual insight, and as a potential blueprint for grounding our society in a more spiritually rewarding worldview.

Hinduism boasts teachings and practices reaching back over 8,000 years, its history dwarfing most other religions. In fact, there is no specific time in recorded history when it began. It is said to have started with time itself. To emphasize the relative ages of the major religions, and the antiquity of Hinduism, Raimon Panikkar, author of The Vedic Experience, cleverly reduced them to proportionate human years, with each 100 years of history representing one year of human life. Viewed this way, Sikhism, the youngest faith, is five years old. Islam, the only teenager, is fourteen. Christianity just turned twenty. Buddhism, Taoism, Jainism and Confucianism are twenty-five. Zoroastrianism is twenty-six. Shintoism is in its late twenties. Judaism is a mature thirty-seven. Hinduism, whose birthday remains unknown, is at least eighty years old—the white-bearded grandfather of living spirituality on this planet.

The followers of this extraordinary tradition often refer to it as Sanatana Dharma, the “Eternal Faith” or “Eternal Way of Conduct.” Rejoicing in adding on to itself the contributions of every one of its millions of adherents down through the ages, it brings to the world an extraordinarily rich cultural heritage that embraces religion, society, economy, literature, art and architecture. Unsurprisingly, it is seen by its followers as not merely another religious tradition, but as a way of life and the quintessential foundation of human culture and spirituality. It is the most accurate possible description of the way things are—eternal truths, natural principles, inherent in the universe that form the basis of culture and prosperity. Understanding this venerable religion allows all people to fathom the source and essence of human religiosity—to marvel at the oldest example of the Eternal Path that is reflected in all faiths.

While 860 million Hindus live in India, forming 85 percent of the population, tens of millions reside across the globe and include followers from nearly every nationality, race and ethnic group in the world. The US alone is home to 2.4 million Hindus, roughly two-thirds of South Asian descent and one-third of other backgrounds.

The Nature of God[edit]

- See also: Monotheism

Some descriptions of Hinduism wrongly state that Hindus do not believe in a one Supreme Being but worship a multiplicity of supreme Gods. A common way that this misconception shows up is in the idea that Hindus worship a trinity of Gods: Brahma, the Creator, Vishnu, the Preserver, and Siva, the Destroyer. To the Hindu, these three are aspects of the one Supreme Being. Indeed, with its vast array of Divinities, Hinduism may, to an outsider, appear polytheistic—a term avidly employed as a criticism of choice, as if the idea of many Gods were primitive and false. But ask any Hindu, and he will tell you that he worships the One Supreme Being, just as do Christians, Jews, Muslims and those of nearly all major faiths. If he is a Saivite, he calls that God Siva. If a Shakta Hindu, he will adore Devi, the Goddess, as the ultimate Divinity. If he is a Smarta Hindu, he will worship as supreme one Deity chosen from a specific pantheon of Gods. If a Vaishnava Hindu, he will revere Vishnu or one of His earthly incarnations, called avatars, especially Krishna or Rama.

Thus, it is impossible to say all Hindus believe this or that. Some Hindus give credence only to the formless Absolute Reality as God; others accept God as personal Lord and Creator. Some venerate God as male, others as female, while still others hold that God is not limited by gender, which is an aspect of physical bodies. This freedom, we could say, makes for the richest understanding and perception of God. Hindus accept all genuine spiritual paths—from pure monism, which concludes that “God alone exists,” to theistic dualism, which asks, “When shall I know His Grace?” Each soul is free to find his own way, whether by devotion, austerity, meditation, yoga or selfless service.

God is unimaginably transcendent yet ubiquitously immanent in all things. He is creator and He is the creation. He is not a remote God who rules from above, but an intimate Lord who abides within all as the essence of everything. There is no corner of creation in which God is not present. He is farther away than the farthest star and closer than our breath. If His presence were to be removed from any one thing, that thing would cease to exist.

A crucial point, often overlooked, is that having one Supreme God does not repudiate the existence of lesser Divinities. Just as Christianity acknowledges great spiritual beings who dwell near God, such as the cherubim and seraphim (possessing both human and animal features), so Hindus revere Mahadevas, or “great angels,” who were created by the Supreme Lord and who serve and adore Him. Each denomination worships the Supreme God and its own pantheon of divine beings. The elephant-faced Lord Ganesha is among the most popular, and is perhaps the only Deity worshiped by Hindus of all denominations. There are Gods and Goddesses of strength, yoga, learning, art, music, wealth and culture. There are also minor divinities, village Gods and Goddesses, who are invoked for protection, health and such earthy matters as a fruitful harvest.

Non-Sectarianism[edit]

Making a big deal of sectarian differences has historically and practically been ignorant. Although some priests and monks had believed in sectarianism and wrote of it, most Hindus, both clergy and laypersons were not interested in sectarian disputes. Marries take place between Hindus of the mainstream of those of Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, and others. Historically there have been some Buddhist and Jain scriptures that are universally accepted because of their non-sectarian nature, as Udayanacharya nots in his Atmatattvaviveka.

For example, the Mattamayura Acharyas were not sectarian. Rudrasiva, the preceptor of Jajalla I was not only well-conversant with his own Siddhantas but also of other sects too.

The Jain king Kharvela was referred to a Deva Pasanda Yatana because he had supported all dharms and had built temples for them.

| Verse(s) | Text |

|---|---|

| "It is only a fool who sees any difference between Rama and Siva." | Chapter 9, Sam-Mohan Tantra |

| "There is no distinction between Visnu and Siva." | Ekamra Purana |

| "One should devoutly worship the one whom he finds most likeable. Worship is purely a matter of faith and there should be no fight for any god's supremacy over the others." | Kurma Purana |

| "He would often say, only fools make distinction between Kali and Krishna, they are the manifestations of the same Power." | P. 395 Ramakrishna as We Saw Him By Swami Chetanananda |

| "O goddess (Parvati), you are Visnu; and Surya and Achyuta are my emanations. The intelligent people say that there is no distinction between them (i.e. between Visnu and Surya). So Visnu and Siva split the one body into two." | |

| "May Hari, Lord of the three worlds, whom the Shaivas worship as Shiva, Vedantins as Brahm, the Buddhists as Buddha, the Logicians, clever in the means of knowledge, as the Creator, devotees of the Jaina doctrine as Arhat, and the Mimamsakas as Karta." | Hanumannātakā |

| Rama tells Shiva, "Those who visualize some difference between Siva and myself, they are not only fools, but also have to suffer the agonies of the hell." | "Patala Khanda", Chapter 46, Padma Purana |

| "Obeisance to the universal spirit of Jina who is Shiva, Dhatri (Brahmā), Sugata (Buddha) and Vishnu." | "The Tumkur Inscription" |

| The Jaina scholar Manibhadra said, "I have no bias for Mahavira , and none against Kapila and others." | Acharanga Sutra |

| "It is said in the Vaishnavite book Pancharatra , " If there is a village or town in which there is no temple to Shiva , you cannot expect Vishnu to reside." | Pañcharātra |

The Nature of the Soul[edit]

What does Hinduism say about the soul? The driving imperative to know oneself — to answer the questions “Who am I?” “Where did I come from?” and “Where am I going?” — has been the core of all great religions and schools of philosophy throughout history. Hindu teachings on the nature of self are as philosophically profound as they are pragmatic. We are more than our physical body, our mind, emotions and intellect, with which we so intimately identify every moment of our life, but which are temporary, imperfect and limiting. Our true self is our immortal soul, the eternal, perfect and unlimited inner essence, a pure being of scintillating light unseen by the human eye, undetectable by any of the human senses, which are its tools for living in this physical world.

Our soul is the source of all our higher functions, including knowledge, will and love. It is neither male nor female. The essence of our soul, which was never created, is immanent love and transcendent reality and is identical and eternally one with God. The Vedas explain, “The soul is born and unfolds in a body, with dreams and desires and the food of life. And then it is reborn in new bodies, in accordance with its former works. The quality of the soul determines its future body; earthly or airy, heavy or light.”

The Vedas teach that the Divine resides in all beings. Our true, spiritual essence is, like God, eternal, blissful, good, wise and beautiful by nature. The joining of God and the soul is known as yoga. We spend so much of our time pursuing beauty, knowledge and bliss in the world, not knowing that these objects of our desire are already within us as attributes of our own soul. If we turn our focus within through worship and meditation, identifying with our true spiritual self, we can discover an infinite inner treasure that easily rivals the greatest wealth of this world.

Hinduism is a mystical religion, leading the devotee to personally experience the Truth within, finally reaching the pinnacle of consciousness where the realization is attained that man and God are one. As divine souls, we are evolving into union with God through the process of reincarnation. We are immortal souls living and growing in the great school of earthly experience in which we have lived many lives. Knowing this gives followers a great security, eliminating the fear and dread of death. The Hindu does not take death to be the end of existence, as does the atheist. Nor does he look upon life as a singular opportunity, to be followed by eternal heavenly existence for those souls who do well, and by unending hell for those who do not. Death for the Hindu is the most exalted of experiences, a profound transition from this world to the next, simultaneously an end and a new beginning.

Despite the heartening glory of our true nature spoken of in scripture, most souls are unaware of their spiritual self. This ignorance or “veiling grace” is seen in Hinduism as God’s purposeful limiting of awareness, which allows us to evolve. It is this narrowing of our awareness, coupled with a sense of individualized ego, that allows us to look upon the world and our part in it from a practical, human point of view. The ultimate goal of life, in the Hindu view, is called moksha, liberation from rebirth. This comes when earthly karma has been resolved, dharma has been well performed and God is fully realized. All souls, without exception, are destined to achieve the highest states of enlightenment, perfect spiritual maturity and liberation, but not necessarily in this life. Hindus understand this and do not delude themselves that this life is the last. While seeking and attaining profound realizations, they know there is much to be done in fulfilling life’s other three goals: righteousness, wealth and pleasure.

In some traditions, the destiny of the soul after liberation is perceived as eternal and blissful enjoyment of God’s presence in the heavenly realms, a form of salvation given by God through grace, similar to most Abrahamic faiths. In others, the soul’s destiny is perfect union in God or in the Infinite All, a state of oneness.

The Nature of the World[edit]

The world is the place where our destiny is shaped, our desires fulfilled and our soul matured. Without the world, known as maya, the soul could not evolve through experience. In the world, we grow from ignorance into wisdom, from darkness into light and from a consciousness of death to immortality. The whole world is an ashram in which all are evolving spiritually. We must love the world, which is God’s creation. Those who despise, hate and fear the world do not understand the intrinsic goodness of all. The world is a glorious place, not to be feared. The Vedas advise, “Behold the universe in the glory of God, and all that lives and moves on Earth. Leaving the transient, find joy in the Eternal.”

There is a false concept, commonly found in academic texts, that Hinduism is world-negating. This depiction was foisted upon the world by 19th-century Western missionary Orientalists traveling in India for the first time and reporting back about its starkest and strangest aspects, not unlike what Western journalists tend to do today. The wild-looking, world-renouncing yogis, taking refuge in caves, denying the senses and thus the world, were of sensational interest, and their world-abandonment became, through the scholars’ eyes, characteristic of the entire religion. Hinduism’s essential, time-tested monastic tradition makes it no more world-negating than Christianity or Buddhism, which likewise have traditions of renunciate men and women living apart from the world in spiritual pursuits.

While Sanatana Dharma proudly upholds such severe ways of life for the few, it is very much a family-oriented faith that supports acquisition of wealth, the pursuit of life’s pleasures and a full engagement in society’s spiritual, intellectual and emotional joys. The vast majority of followers are engaged in family life, firmly grounded in responsibilities in the world. Young Hindu adults are encouraged to marry; marriages are encouraged to yield an abundance of children; children are guided to live in virtue, fulfill duty and contribute to the community. The emphasis is not on self-fulfillment and freedom but on duty and the welfare of the community, as expressed in the phrase, “Bahujan hitaya, bahujan sukhaya,” meaning “the welfare of the many and the happiness of the many.”

Hindu scriptures speak of three worlds of existence: the physical, subtle and causal. The physical plane is the world of gross or material substance in which phenomena are perceived by the five senses. It is the most limited of worlds, the least permanent and the most subject to change. The subtle plane is the mental-emotional sphere that we function in through thought and feeling and reside in fully during sleep and after death. It is the astral world that exists within the physical plane. The causal plane pulsates at the core of being, deep within the subtle plane. It is the superconscious world where the Gods and highly evolved souls live and can be accessed through yoga and temple worship.

Hindus believe that God created the world and all things in it. He creates and sustains from moment to moment every atom of the seen physical and unseen spiritual universe. Everything is within Him. He is within everything. God created us. He created time and gravity, the vast spaces and the uncounted stars. Creation is not the making of a separate thing, but an emanation of Himself. God creates, constantly sustains the form of His creations and absorbs them back into Himself. According to Hinduism, the creation, preservation and dissolution of the universe is an endless cycle. The creation and preservation portion of each cycle is a period of approximately 309 trillion years, at which point Mahapralaya, the Great Dissolution, occurs. Mahapralaya is the absorption of all existence—including time, space and individual consciousness, all the worlds and their inhabitants—in God, a return of all things to the source, sometimes likened to the water of a river returning to the sea. Then God alone exists until He again issues forth creation.

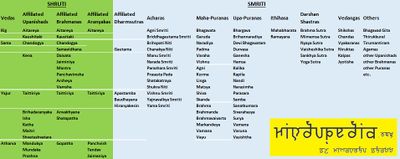

Hindu Scriptures[edit]

All major religions are based upon a specific set of teachings encoded in sacred scripture. Christianity has the Bible and Islam has the Koran. Hinduism does not have any official scripture(s) and any 2 Hindus might not rely on the same text for a basis of principles, but the Five Precepts take priority over all texts. It’s source of scriptures are, however, the Vedas. The Upanishads, Brahmanas, and Aranyakas are auxiliary to the Vedas. All smriti texts are ancillary to the Vedas. The reason why there is no official scripture for Hinduism (or for most Arya dharms) is because Moksha must be obtained by practice, not faith in the legitimacy of a scripture.

“If any injunction in a shastra is opposed to truth, non-violence, Brahmacharya, it is unauthentic, in whichever the shastra in which it is found. The shastras are not above reason. We can reject any shastra which reason can not follow.” - Mahatma Gandhi[7]

Hinduism proudly embraces an incredibly rich collection of scriptures; in fact, the largest body of sacred texts known to man. The holiest and most revered are the Vedas and Agamas, two massive compendia of shruti (that which is “heard”), revealed by God to illumined sages many millennia ago. It is said the Vedas are general and the Agamas specific, as the Agamas speak directly about the details of worship, the yogas, mantra, tantra, temple building and such. The most widely known part of the Vedas are the Upanishads, which form the more general philosophical foundations of the faith.

The array of secondary scripture, known as smriti (that which is “remembered”), is equally vast, the most prominent and widely celebrated of which are the Itihasas (epic dramas and history—specifically the Ramayana and Mahabharata) and the Puranas (history). The ever-popular Bhagavad Gita is a small portion of the Mahabharata. The Vedic arts and sciences, including ayurveda, astrology, music, dance, architecture, statecraft, domestic duty and law, are reflected in an assembly of texts known as Vedangas and Upavedas. Moreover, through the ages God-realized souls, sharing their experience, have poured forth volume upon volume that reveal the wonders of yoga and offer passionate hymns of devotion and illumination. The creation of Hindu scripture continues to this day, as contemporary masters reiterate the timeless truths to guide souls on the path to Divinity.

"But I would like to believe Hinduism is too valuable for humanity, and sacred Indian books contain too much precious and unique knowledge that it will not sink in oblivion." - Aleksandr Zinovyev

A clear sign that a person is a Hindu is that he embraces Hindu scripture as his guide and solace through life. While the Vedas are accepted by all denominations, each lineage defines which other scriptures are regarded as central and authoritative for its followers. Further, each devotee freely chooses and follows one or more favorite scriptures within his tradition, be it a selection of Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, the Tirumantiram or the writings of his own guru. This free-flowing, diversified approach to scripture is unique to the Hindu faith. Scripture here, however, does not have the same place as it does in many other faiths. For genuine spiritual progress to take place, its wisdom must not be merely studied and preached, but lived and experienced as one’s own.

- Why are there contradictions

Contradictions mainly occur within the smriti texts, and the reason for this is that scriptures are categorized as 'smriti' if they are merely remembered and not orally passed down so accurately as the shruti texts were. According to Pollock, stories which are no longer available to be heard in recitation and are merely remembered, are classified as smriti.[8] This raises the problem of accuracy - if stories are remembered and were not thoroughly passed down as the shruti texts were, they're reliability is questionable and that is why contradictions occur within them. It is said that the Puranas themselves come from a Mula-Purana ("Root Purana"), but as this is only 'remembered' (smriti) and not 'received' (shruti), there are some important events and persons which are missing from texts.

The 4 Pillars of Hinduism have the ultimate authority in Hinduism, then shruti texts, and then smriti texts. For this reason, a Hindu is not required to place faith within a particular scripture for salvation - instead salvation is based on his or her karmas.

"It is important to realise that if we are to remain true to the shastra it is not because they represent the views of the seers but because they contain the rules founded on the Vedas which are nothing but what Ishvara has ordained. That is the reason why we must follow them. It is my duty to see that the shastras are preserved as they are. I have no authority to change them." - Shankaracharya

Hinduism in Practice[edit]

Hinduism has three sustaining pillars: temple worship, scripture and the guru-disciple tradition. Around these all spiritual disciplines revolve, including prayer, meditation and ritual worship in the home and temple, study of scripture, recitation of mantras, pilgrimage to holy places, austerity, selfless service, generous giving, good conduct and the various yogas. Festivals and singing of holy hymns are dynamic activities.

Temples hold a central place of importance in Hindu life. Whether they be small village sanctuaries or towering citadels, they are esteemed as God’s consecrated abode. In the temple Hindus draw close to the Divine and find a refuge from the world. God’s grace, permeating everywhere, is most easily known within these holy precincts. It is in this purified milieu, where the three worlds (physical, astral and causal) commune most perfectly, that devotees can establish harmony with God, the Gods and their angelic helpers, called devas. Traditional temples are specially sanctified, possessing a ray of spiritual energy connecting them to the celestial worlds.

Temple rituals, performed by Hindu priests, take the form of puja, a ceremony in which the ringing of bells, passing of flames, presenting of offerings and intoning of chants invoke the devas and Gods, who then come to bless and help the devotees. Personal worship during puja may be an expression of festive celebration of important events in life, of adoration and thanksgiving, penance and confession, prayerful supplication and requests, or contemplation at the deepest levels of superconsciousness. The stone or metal Deity images enshrined in the temple are not mere symbols of God and the Gods; they are not mere inert idols but the forms through which divine love, power and blessings flood forth from the inner world of the Gods into this physical world. Devout Hindus adore the image as the Deity’s physical body, knowing that the God or Goddess is actually present and conscious in it during puja, aware of devotees’ thoughts and feelings and even sensing the priest’s gentle touch on the metal or stone.

Priests, known as pujaris, hold a central place of honor and importance. Each temple has its own staff of priests. Some temples appoint only one, while others have a large extended family of priests to take care of the many shrines and elaborate festivals. Most are well trained from early childhood in the intricate liturgy. These men of God must be fully knowledgeable of the metaphysical and ontological tenets of the religion and learn hundreds of mantras and chants required in the ritual worship. Generally, pujaris do not attend to the personal problems of devotees. They are God’s servants, tending His temple home and its related duties, never standing between the devotee and God. Officiating priests are almost always married men, while their assistants may be unmarried young men or widowers.

It most important to live near a temple, as it is the center of spiritual life. It is here, in God’s home, that the devotee nurtures his relationship with the Divine. Not wanting to stay away too long, he visits weekly and strives to attend each major festival, and to pilgrimage to a far-off temple annually for special blessings and a break from his daily concerns. For the Hindu, the underlying emphasis of life is on making spiritual progress, while also pursuing one’s family and professional duties and goals. He is conscious that life is a precious, fleeting opportunity to advance, to bring about inner transformation, and he strives to remain ever conscious of this fact. For him work is worship, and his faith relates to every department of life.

Hinduism’s spiritual core is its holy men and women — millions of sadhus, yogis, swamis, vairagis, saints and satgurus who have dedicated their lives to full-time service, devotion and God Realization, and to proclaiming the eternal truths of Sanatana Dharma. In day-to-day life, perhaps no facet of dharma is as crucial as the spiritual teacher, or satguru. These holy men and women are a living spiritual force for the faithful. They are the inspirers and interpreters, the personal guides who, knowing God themselves, can bring devotees into God consciousness. Hindus believe that the blessing — whether a look, a touch or even a thought — coming from such a great soul helps them in their evolution, changes patterns in their life by cleaning up areas of their subconscious mind that they could not possibly have done for themselves. They further believe that if his shakti is strong enough, and if they are in tune with him enough, they will be empowered to really begin to meditate.

In all Hindu communities there are gurus who personally look after the spiritual practices and progress of devotees. Such preceptors are equally revered whether they are men or women. In few other religions are women allowed such access to the highest seats of reverence and respect.

Within the Hindu way is a deeply rooted desire to lead a productive, ethical life, following dharma. Among the many virtues instilled in followers are truthfulness, fidelity, contentment and avoidance of greed, lust and anger. A cornerstone of dharma is ahimsa, noninjury toward all beings. Vedic rishis who revealed dharma proclaimed ahimsa as the way to achieve harmony with our environment, peace between people and compassion within ourselves. Devout followers tend to be vegetarian and seek to protect the environment. Many individuals of all faiths are concerned about our environment and properly preserving it for future generations. Hindus share this concern and honor and revere the world around them as God’s creation. Their traditions have always valued nature and cared for it. They find it natural to work for the protection of the Earth’s diversity and resources to achieve the goal of a secure, sustainable and lasting environment.

Selfless service to God and humanity, known as seva, is widely pursued as a way of softening the ego and drawing close to the Divine. Charity, dana, is expressed though myriad philanthropic activities, especially feeding others. Hindus wear sectarian marks, called tilaka, on their foreheads as sacred symbols, distinctive insignia of their heritage. Rather than burial, they prefer cremation of the body upon death, which quickly releases the soul from its earthly frame, allowing it to continue its evolutionary journey.

Perhaps one of Hinduism’s most refreshing characteristics is that it encourages free and open thought. Scriptures and gurus encourage followers to inquire and investigate into the nature of Truth, to explore worshipful, inner and meditative regimens to directly experience the Divine. This openness is at the root of Hinduism’s famed tolerance of other cultures, religions and points of view, capsulated in the adage, “Ekam sat viprah bahuda vadanti,” meaning “Truth is one, the wise describe it in different ways.” The Hindu is free to choose his path, his way of approaching the Divine, and he can change it in the course of his lifetime. There is no heresy or apostasy in Hinduism. This, coupled with Hinduism’s natural inclusiveness, gives little room for fanaticism, fundamentalism or closed-mindedness anywhere within the framework of Hinduism. It has been aptly called a threshold, not an enclosure.

Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, renowned philosopher and president of India from 1962 to 1967, summarizes in The Hindu View of Life: “The Hindu recognizes one Supreme Spirit, though different names are given to it. God is in the world, though not as the world. He does not merely intervene to create life or consciousness, but is working continuously. There is no dualism of the natural and the supernatural. Evil, error and ugliness are not ultimate. No view is so utterly erroneous, no man is so absolutely evil as to deserve complete castigation. There is no Hell, for that means there is a place where God is not, and there are sins which exceed His love. The law of karma tells us that the individual life is not a term, but a series. Heaven and Hell are higher and lower stages in one continuous movement. Every type has its own nature which should be followed. We should do our duty in that state of life to which we happen to be called. Hinduism affirms that the theological expressions of religious experience are bound to be varied, accepts all forms of belief, and guides each along his path to the common goal. These are some of the central principles of Hinduism. If Hinduism lives today, it is due to them.”

Compared to other religions[edit]

Although there are more Abrahamic (i.e., Druze, Mandeanism) and Taoic (i.e., Cheondogyo) religions, as well as other (i.e., Yarsanism) world religions, the table below accounts for only the major ones of those classes.

Sanatan Dharm compared to other religions:

| Religion | Hinduism (ॐ) |

Buddhism (☸) |

Bon (卍) |

Jainism (卐) |

Kirantism (☀) |

Sikhism (☬) |

Zoroastrianism (🔥) |

Baha'i (✴) |

Christianity (✞) |

Mormonism (⬢⬡⬢⬡) |

Islam (☪) |

Judaism (✡) |

Confucianism (儒家) |

Daoism (☯️) |

Mohism (墨家) |

Shinto (⛩️) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Ārya | Ārya | Ārya | Ārya | Ārya | Ārya | Ārya | Abrahamic | Abrahamic | Abrahamic | Abrahamic | Abrahamic | Taoic | Taoic | Taoic | Taoic |

| Central theology (among others) | Panentheism | Panentheism | Panentheism | Panentheism | Panentheism | Panentheism | Panentheism | Monotheism | Monotheism | Monotheism | Monotheism | Monotheism | Pantheism | Pantheism | Pantheism | Pantheism |

| Soteriology | Moksh | Moksh | Moksh | Moksh | Moksh | Moksh | Garo-nmāna | Christian heaven (New Jerusalem) |

Christian heaven (Celestial Kingdom of God) |

Islamic heaven (Jannah) |

Jewish heaven (Shamain) |

Tian | Tian | Tian | Takamagahara | |

| Means of salvation | Practicing the Panchvrat and any of 3 yogas | Practicing the Panchvrat and Ashtanga Marg, and possibly adding worship | Practicing the Panchvrat and Dzogchen, and possibly adding worship | Practicing the Panchvrat and any of 3 yogas | Practicing the Panchvrat and adding worship to it | Practicing the Panchvrat and adding worship to it | Faith in the Trinity | Faith in the Trinity | Worshiping Allah, and fasting during Ramadan | Worshiping Yahweh, and practicing the Mosaic Law | ||||||

| Pantheon | Brahm in any form | Brahm in any form (usually as Tathāgats) | Kuntu Zangpo and subordinate Buddhas | Brahm in any form (usually as Tirthankars) | Yumā Sammang and subordinate devas | Brahm and subordinate Satgurus | Āhura Māzda and subordinate yazatas | Ya Baha'ul'Abha | Yahweh (The Father, Son [Word], and Holy Spirit) | Yahweh (The Father, Son [Word], and Holy Spirit) | Allah, Allah’s Word (Kalimatullah or Jesus), and Allah’s Spirit (Roohullah)[9] | Yahweh (singular) | Shang Di and subordinate shens | Sānqing (Yuanshi Tianzun, Lingbao Tianzun, Daode Tianzun) and subordinate shens | Masubi and subordinate kami (usually in the form of distant ancestors) | |

| Commandments | Panchvrat | Panchvrat | Panchvrat | Panchvrat | Panchvrat | Panchvrat | Decalogue | Decalogue | Qu'ranic commandments | Decalogue | 4 Principles | |||||

| Cosmic order of ethics | Rta | Hukam | Asha | Li | Ganying | Fa | Lannagara | |||||||||

| Worship hall | Mandir | Chaityagriha | gSas Khang | Jinalāy | Mangkhim | Gurudwār | Dar Be-Mehr | Mashriqu'l-Adhkār | Church | Church | Mosque | Beit Knesset | Kǒngmiāo | Dāoguān | Jinja | |

| Monastery | Math | Brahm Vihār | Ling Yungdrung Gon | Jin Vihār | Priory | |||||||||||

| Divinity school | Ghatika | Seminary | Seminary | Madrasa | Yeshiva | |||||||||||

| Outlook on new ideas (religions or otherwise) | Samadarshan | Pratitya-samutpād | Pluralism | Anekāntavād | Pluralism | Pluralism | Pluralism | Pluralism | Puritanism | Puritanism | Puritanism | Puritanism | Pluralism | Pluralism | Pluralism | Pluralism |

| Credo (in English) |

Shuti, smriti, good conduct, one’s own conscience Proper and purposeful desire [for good resolution] is customary of the root of gentleness' dharm. |

I take refuge in the Ārya Buddha, I take refuge in the Ārya dharm, I take refuge in the Ārya sangh. |

Aum. In the Lama, Buddha, Bon, and Shenrab, Yidam, Rigzin, Khandro, and protectors of the teaching. |

Proper faith, knowledge, and conduct is that path of Moksh | I profess myself a worshipper of Āhura Māzda, in accordance with Zārathustra, abstaining from dāevās, and act according to Māzdayasna. | The fundamental purpose animating the Faith of God and His Religion is to safeguard the interests and promote the unity of the human race, and to foster the spirit of love and fellowship amongst men. | [Nicene Creed] | [Shahada] | [Shmah] | |||||||

| Motto | Vasudhaiva kutumbakam | Sabbapapassa akaranam, ku salassa upasampada, |

Parasparopagraho Jivanām | Jo bole so nihāl, Sat Sri Akāl |

Humata, Huksta, Huvarshta |

Hosanna | Hosanna | Allahu Akbar | Hallelujah | |||||||

| Short mantra | Aum Namo Brahm | Aum Namo Buddhānam | Aum Ma Tri Mu Ye Sa | Aum Namo Jinānam | Aum Yumā Sammang | Aum Sat Nām | Ahunam Nemo Āhura | Amen | Amen | Amin | Amen | |||||

| Regular mantra | Gāyatri Mantra | Awgatha | Sem chog gye ching sol wa dab[3] |

Namokar Mantra | Mul Mantra | Yatha Ahu Vairyo | The Lord's Prayer | The Lord's Prayer | Amida | |||||||

| Greeting | Namaste | Jai Jinendra | Wāheguruji ka Khālsā Wāheguruji ki fateh | Hamazor hama asho-bed | ||||||||||||

| Source of scriptures | 4 Vedas | 3 Pitākas | Srid-pa'i Mdzod-phug | 12 Angas | Kirant Mundhum | Sri Guru Grānth Sahib | Zhand Avesta | Kitāb-i-Aqdas | 4 Gospels | Book of Mormon | Qu'ran | 5 Scrolls | 5 Classics | Tao Te Ching | Mozi | Kojiki |

- Classification

- See also: Introduction to Sanātan Dharm

Sanatan Dharm is an Arya dharm, meaning it's based on Moksha. This makes the dharm a part of the Ārya Samudāy.

- Central theology

- See also: Theology

Because Hinduism along with the rest of the Arya Samuday recognize one force above all, which is omnipresent and in which all things reside, they are of the panentheist classification, known as Ishavasyam in Sanatan texts. It is essentially a form of monotheism, especially because this central force is Brahm, who can be recognized as a personal God (i.e., Krishna, Shiva) or impersonal (i.e., Alakh Niranjan.)

- Soteriology

Salvation in Sanatan Dharm is Moksha.

"No theistic system, including Christianity, has been able to reconcile the goodness and omnipotence of God with a world of pain and sin.... The Hindu advocate of karma may be quite right that such a belief provides a powerful incentive for personal ethics.... At best, therefore, these basic Hindu beliefs inspire a self-centered morality (and social ethics), whose sole criterion for ethical behavior is the merit being stored up by karma." - Dr. Creighton Lacy

- Means of Salvation

Salvation is based on practicing the five precepts and any of the 3 yogas.

Some religions are based on faith or faith plus works, but in Hinduism it's based on the idea that anyone can attain Moksh, even if they are not Hindu or of the Arya Samuday - as long as they lived by the five precepts and practiced any of the 3 yogas (i.e., a monk of another religion) they would achieve salvation.

- Pantheon

- See also: Brahm

| All this is Brahman. Everything comes from Brahman, everything goes back to Brahman, and everything is sustained by Brahman. One should therefore quietly meditate on Brahman. Each person has a mind of his own. What a person wills in his present life, he becomes when he leaves this world. One should bear this in mind and meditate accordingly. | ||

As Sanatan Dharm is not stringent on worship or Bhakti-yoga, worship is not necessary but it does preserve a connection between the soul and the true reality/Self (Brahm or Parmatma.) Brahm is one, and Hindus typically worship It in an Ishta-dev or Personal God (i.e., as Shiva, Krishna, Durga.)

As there is no strict rules on worship, prayers are offered even to spirits, such as of ancestors. Worship is conducted through instruments, including idols and plants, though they are not necessary and simply the soul of Brahm can be communicated with by prayers.

- Commandments

- See also: Ethics of Hinduism

The required rules for Hindus are the Five Precepts or Panchvrat.

- Cosmic order of ethics

| "Oh Indra, lead us on the path of Rta on the right path over all evils." | ||

—Rig Veda 10.133.6 | ||

- Outlook on new ideas

- See also: Right Worldview

| May noble and auspicious thoughts come to us from all over the Universe | ||

—Rig Veda 1.89.1 | ||

New ideas are viewed analytically with a constructivist or pluralist mindset, which has been reflected by philosophers, such as Vasudev Krishna and Mahatma Gandhi, as loksangraha or “well-being of the world.” It relates to the principles of samadarshan and trikarana shuddhi. Exploring new ideas is encouraged to be done via a shastrartha (dialogue.) A common Sanskrit dictum is "Vade vade jayate tattvabodho," meaning, "Through continuous dialogue alone does one arrive at the core truth."

- Credo

- See also: Sadachara, Sanātan Dharm Principle

| Śruti smriti sadāchāra svasya cha priyamatmanā Samyak samkalpajo kāmo dharmamulamidam smritam |

||

—Yajnavalkya Smriti 1.8 | ||

Translation:

"Shuti, smriti, good conduct, one’s own conscience

Proper and purposeful desire [for good resolution] is customary of the root of gentleness’ dharm"

The Hindu credo refers to conduct with others. While the Vedas are not the official scriptures of Sanatan Dharm, they are the first ones and most other scriptures have Vedas’ concepts as source. What the Vedas mention about conduct is classed into 2 categories; Yamas (Five Precepts) and Niyamas. The Smritis reaffirm them. Good conduct is expected towards the soul attaining Moksha. Finally, at times of confusion, one’s own conscience should be applied towards determining the best or moral outcome of the situation.

Quotes regarding self-restrain from Sanatan and other Arya teachers:

| Krishna | Narada | Patanjali | Gautam Buddha | Mahavir | Guru Nanak | Mahatma Gandhi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Motto

| On who sees all creatures as if they were his own selves and himself in others - his mind rests in peace | ||

—Yajur Veda 40-46 | ||

"Vasudhaiva kutumbakam" from Maha Upanishad 6.72, meaning "The whole world is one family" is in alignment with the constructivist Hindu outlook on new ideas. As a result, Hindus throughout centuries have given refuge to persecuted peoples, such as Baha'is, Jews, Syriac Christians, Tibetan Buddhists, Zoroastrians, and others.

- Short mantra

- See also: Chanting Om

This aphorism is would be the veneration of what the most holy spirit in Hinduism, Brahm. While Hindus often say short mantras dedicated to Brahm within a particular form, such as "Aum Nama Shivay" or "Aum Namo Vasudevay", they essentially are saying, "Aum Namo Brahm."

- Regular mantra

- See also: Mantra Marga

| All that exists in this world, whatever there is, is gāyatrī. It is the word that is gāyatrī, for the word gives names to all things and it also tells them not to fear. | ||

The Gayatri Mantra is the most important mantra for Hindus because it's non-sectarian and is dedicated to the highest being, Brahm.

- Namaste

- See also: Namaskāra

This is the most popular Hindu greeting and means, "I bow to the divine in you." It is humble and highlights the presence of Brahm within souls.

- Source of scriptures

- See also: Overview Of Scriptures

Nigama means, "come as such," while Āgama means, "come out from."[15] Because the Āgama (Smriti) scriptures come out from or have their source in the Vedas (Shruti), the latter is the source.

References[edit]

- ↑ Yajur Veda, Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 4.4.6

- ↑ Krishna Yajur Veda, Shvetashvatara Upanishad 4.14-15

- ↑ Yajur Veda, Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 4.4.5

- ↑ Tirukural 31-32

- ↑ Chapter 16, verse 21, Bhagavad Gita

- ↑ Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 16

- ↑ Hindu Dharma By M. K Gandhi

- ↑ P. 143 Poetics of Conduct: Oral Narrative and Moral Being in a South Indian Town By Leela Prasad

- ↑ Because Islam is derived and borrows from Christianity, this concept is stated in the Qu’ran but Muslims refute that it borrows from the Christian Trinity. The Qu’ran distinctly says Jesus is Kalimatullah, originally to lure Christian converts but today it’s considered blasphemy to equate Allah with His Word and Spirit.[1]

- ↑ Because Bon's 'Jewels of Refuge' or (dkon-mchog-bzhi, skyabs-gnas-bzhi or mchog-gnas-bzhi) are these four

- ↑ Bhagavad-Gītā 6.5-7

- ↑ Bhagavad Purana 7.8.11[107]

- ↑ Uttaradhyayana Sutra 9.34-36

- ↑ Japu 26, Guru Granth 6

- ↑ P. 7 Calcutta Sanskrit College Research Series Issue 74, By Sanskrit College (Calcutta)

Related Articles[edit]

- Samadarshan

- Sadachara

- Ethics of Hinduism

- Key Beliefs

- Basic Philosophical Concepts

- Darsana

- Upanishad

- Dharma

- This article was originally published in the April/May/June 2009 edition of "Hinduism Today"

External Resources[edit]

- “What's The Oldest Surviving Religion In The World?” By Tom Hale (Published August 11, 2023)